It seems like a high percentage of my posts here relate to Meniere’s disease. So many questions, with very few definite answers. There are many theories as to what causes the triad of symptoms (vertigo, tinnitus, hearing loss) associated with a Meniere’s episode, and many treatment options available. If you think about it, if any one theory explained all aspects of the disease, or if there was solid evidence to support a theory, we may not have so many alternative theories. Let’s explore some of the more popular theories, and see where the evidence leads us.

Theories of Meniere’s Disease

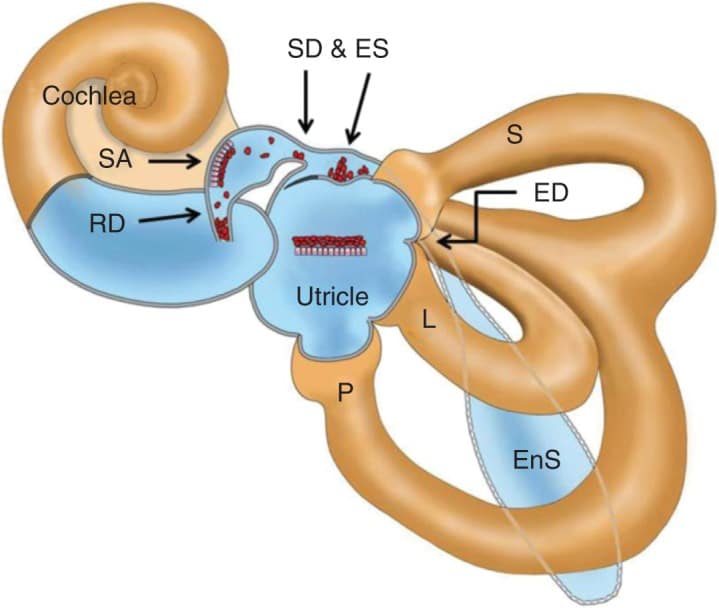

I will start with the most recent entry. Yamane and colleagues in Japan have published two papers in the past few years proposing a novel theory on Meniere’s disease, with some impressive supporting evidence. First, a quick review: the labyrinth (balance part of the inner ear) is a series of interconnected chambers and tunnels. There are motion sensors in each of the chambers and tunnels. When you move your head, the inner ear fluid (endolymph) lags behind and stimulates these sensors, sending messages to the brain regarding the speed and direction of head movement. The key word here is “interconnected.”

One theory is that the endolymph flows throughout these chambers and tunnels, and more than one theory about Meniere’s disease suggests that the disease may be caused by a blockage somewhere in the labyrinth, causing endolymph to build up (sort of a “mini-dam”). There are some very narrow points where different chambers in the labyrinth connect.

So, what could be blocking these narrow points? Yamane suggests that otoconia dislodged from the saccule may find its way into the narrow opening between the saccule and the cochlea (the hearing part of the inner ear). This narrow path is known as the Reuniting Duct.

As discussed by Yamane, we are quite confident that BPPV is the result of otoconia being dislodged from the utricle, gravitating into one of the semi-circular canals. Why would one think that the saccule does not also discharge excess otoconia at times? And where does that saccular otoconia go? And, is there any evidence to support this theory?

Yamane performed 3D CT scanning of the labyrinth in a series of people with definite Meniere’s disease in one ear, and compared those findings to the opposite healthy ear as well as ears of people that do not and never had Meniere’s disease. They were looking specifically at the reuniting duct to see if appeared open or blocked. They found that the reuniting duct appeared blocked in one third (37%) of the affected ears in patients with Meniere’s disease, but only in 10% of the opposite healthy ears. In the group of patients with no history of Meniere’s disease, they found no (0%) blockages.

They summarize their article hypothesizing whether opening or widening these narrow points that are susceptible to blockage may be an effective treatment for Meniere’s disease. This theory has yet to be tested.