I have actually heard this expletive from several musicians over the years. And if you think that it’s just from a Rocker, you are wrong, although, Rock musicians do tend to use more creative expletives than their classical colleagues. The study of musician expletives would make an interesting Capstone study for an interested graduate student of audiology.

What can be done when a musician shows up at a gig and finds it just unbearable? Perhaps the venue is not set up for their in-ear monitors which they have been using as a quasi-form of hearing protection? Perhaps the drummer for the gig is new and just sitting in for the evening and the band is really quite loud? A musician just can’t say, “Oh sorry, I can’t play tonight because it’s too loud”. Actually they can say that, at least in many European countries, because of the occupational laws that can protect them; a worker simply should not be forced to work in an unsafe environment. In North America, the available regulations are quite watered down and would have questionable validity even if followed to the letter. This is a musician’s work and they need to perform at this gig.

So, John (not his real name… it’s actually Peter) shows up at a gig, finds that the available amplification system can’t support his ear monitors, he’s left his earplugs at home in his other instrument case, and there is a new drummer named Alex (not his real name… it’s actually Frank) who appears to be “over-the-top macho”. And the first set starts in ten minutes.

There are a number of things that John can do – none of them perfect, but perhaps taken together, they can make the evening more bearable and safer for his long term hearing status.

The first thing John should do is move the drum kit over to the left side of the stage where the high hats (typically on the drummer’s left side) are as far from others as is possible. It would be nice to lock Alex (the drummer) in a closet but this is probably not smart since technically it’s assault, but I can understand John wanting to do this. The high hats are the most intense element in a drum kit and if we can at least extend the distance between the high hat cymbal and everyone else, this is probably a good thing.

The second thing that John should do is go to the washroom (and for our American readers, the “bathroom”) and get some toilet paper- roll it up, open your mouth, and jam the wad in your ears. This may seem odd, but when you open your mouth, the back part of the jaw (called the condyle) slides forward thereby increasing the front-back dimension of John’s earcanal. (Actually it’s only the front, anterior dimension). This has the effect of allowing John to insert the wad of toilet paper further into his ear canal. The toilet paper idea, especially if inserted deeply (and I should point out that this is clean toilet paper) can provide about 9-10 dB of low frequency attenuation and about 15-18 dB of high frequency attenuation. This may not sound like a lot, but if every 3 decibels of attenuation is one-half the potential damage, then 9 dB will be 1/8 of the potential damage. That is, John can be exposed 8 times as long with toilet paper as compared with nothing in his ears. And for those who like mathematics, it would be (1/2)3. For those who do not like mathematics, unfortunately it is still the same thing.

I have done these measurements only with clean, dry toilet paper but I would presume that it would provide more attenuation if the toilet paper was, uh, damp. I haven’t investigated the effect with different “dampening agents”. This would be an interesting Capstone paper for some intrepid graduate student in audiology.

The third thing that John can do is to refrain from smoking- higher levels of carbon monoxide (and smoking in general) have been correlated with a greater susceptibility of hearing loss. Besides, as there are a lot of other downsides to smoking, John should not smoke in any event!

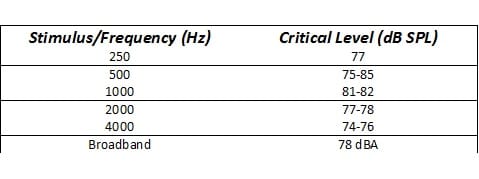

The fourth thing that John can do is to take his breaks outside of the venue (or in a closet) where it may be quieter. It is not the peak or average sound level that is the only culprit- it is the duration of the music as well. If John can take a break in relative quiet, sometimes referred to as environments with lower than a critical level (see chart below), this will provide John with some reprieve from the noise or music dosage exposure. It is the dose that John should be aware of- the sound level and the duration.

Critical levels were studied in the 1970s and early 1980s, and although the paradigms differed slightly from study to study, as did the definition of critical level, these were levels below which a temporary threshold shift (TTS) would not typically be observed. If you can restrict your exposure to levels below the critical level, then this would not appreciably contribute to the dose of noise or music exposure. While TTS is not permanent hearing loss, it is related in the sense that in order to sustain a permanent hearing loss, you must have had some TTS first. More on “critical level” will be found in my next blog.

Thanks for the practical tips!

For *dampened* wadded toilet paper, informal attenuation figures (by Dr. Stéphane Pigeon) are here:

http://www.audiocheck.net/earplugreviews_toiletpaper.php

neat 🙂