This post discussion is a continuation of previous posts related to comments that many hearing professionals have expressed with concerns that OTC/PSAP hearing aid sales will result in dissatisfied users because:

- The instruments are not professionally fitted

- An audiogram is necessary

- OTC-sold devices (previously defined as PSAPs) are of poor quality and will not meet the needs of the hearing impaired, and

- Poor experiences by the purchaser will discourage them from seeking additional assistance and purchasing a “real” hearing aid

- A Universal, basic hearing aid cannot manage all hearing losses

This post relates to issue #5, that a universal, basic hearing aid cannot manage all hearing losses.

A Universal, basic hearing aid cannot manage all hearing losses

This is a correct statement. There is no expectation that a universal basic hearing aid can fit all needs, just as no premium-priced hearing aid can solve all hearing needs, even with all the programming parameters available. But, aside from this, the OTC/PSAP instruments are not intended for the entire market, but assigned to the mild-to-moderate hearing level category, which would be expected to require less adjustability than more severe and divergent hearing losses which may be better fitted with multi-parameter adjustable hearing aids. This comparison might be analogous to a mild headache being treated with an aspirin, but a severe migraine requiring something much more potent and specific.

What is a basic hearing aid?

Reading through the discussions related to OTC/PSAP versus “real” hearing aids, one gets the sense that a basic hearing aid as defined by the industry is a “real” hearing aid, having fewer options/features, designed as a “starter” listening device and intended to be replaced relatively soon with a more “premium” instrument because it most likely will not adequately meet the needs of the hearing-impaired individual. Following this line of reasoning, a basic hearing aid is a “watered-down, lesser” device because it does not include multiple features and command a premium price.

Years ago, what is known as the Harvard Report1 and the United Kingdom Medical Research Council2 suggested that the majority of patients with hearing impairment could be fitted with a hearing aid having a standard response with the slope expressed in dB per octave. They suggested that a range of slope between 0 and +6 dB/octave, along with various other recommended parameters (e.g. sufficient gain), is the desired response. Would this define a basic hearing aid?

Difficulty in Describing a Basic Hearing Aid

What was a premium device in the past is now considered a basic hearing aid. Throughout the history of hearing aid development, it would be fair to say that the description of a basic hearing aid has changed, to the point that defining a basic hearing aid has become essentially an impossible task. The reason is because what is defined as a premium hearing aid today, is likely to become the basic hearing aid of tomorrow. Which means, that the description of a basic hearing aid may have to be redefined on essentially a continuing basis. As such, this would follow the history of hearing aids. A few years ago, a hearing aid having compression, a volume control, and a couple of trimmers for response and output change was considered a premium device. Today, it might not even be considered a basic hearing aid, with many PSAPs having these, and often even more, features.

It is acknowledged that not all OTC/PSAP hearing instruments are of the same quality, just as not all professionally-sold hearing aids are of the same quality. So, where are the red lines in the sand for OTC/PSAP hearing device quality or for hearing aid quality? Is it a distinct line, or is it spread out over a wide range with overlap? If spread out over a wide range, do the limits drop off suddenly, or are they merged into the next category? If merged, how is the overlap handled? Of course, it would be nice if we could actually identify hearing aid quality.

Should a hearing device be considered basic based on its technology, user satisfaction, and/or benefit? If based on these categories, we might be in for an unexpected surprise.

For example, as referenced in a previous post, and replicated here in Figure 1, in a survey comparing hearing aid benefit and satisfaction versus technology (comparing a basic hearing aid with a cost of about $500 up to one costing $4000 to the consumer), the average judged value of hearing aids (of well-fitted devices, along with patient counseling), was about the same, regardless of the purchase price.3

Figure 1. The average judged value for all the hearing aid devices, regardless of the purchase price, was about 60, regardless of the advanced features. (Calculated by Killion from Van Vliet, 2002 data and replotted here).

In a comparison of basic versus premium hearing aid acceptability of technologies on non-speech sound acceptability, no evidence was found to show that premium hearing aids yielded greater acceptability than basic hearing aids.4

OTC/PSAP Suggested Performance Standards

The Consumer Technology Association (CTA) has proposed standards for Personal Sound Amplification Performance Criteria in an attempt to help define OTC/PSAP products. This author finds these unreasonable, impractical, and not helpful to providing more amplification to the non-hearing aid user market and will explain the reasons for these comments in a series of later posts.

How Do OTC/PSAPs Compare with Traditional Hearing Aids?

With the discussion of OTC/PSAP hearing devices, numerous remarks have been made about the products that might be sold to consumers. Comments range from saying that such products will destroy user’s hearing, are doomed to failure because consumers will not be satisfied with either the product and/or service, or will have a bad experience which will drive individuals away from “appropriate” hearing aid fitting. These comments are mostly speculations without supporting evidence. This is not to say that such actions might not occur, but evidence would help.

Paraphrasing a good and knowledgeable friend when confronted with such comments: That individuals will be driven away with having a poor experience is like saying a person may refuse to eat again because of a bad food experience in a restaurant. It is probably fair to say that people are smarter than this (attributed to Mead Killion).

What Does Available Data Tell Us?

Three recent reports state that OTC/PSAP hearing devices are inferior products.5,6,7 A previous post identified problems with product selection with each of these studies, suggesting that there is nothing definitive to be taken from them.

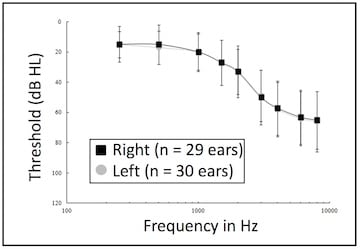

Figure 2. Mean audiogram for the 32 subjects. Error bars represent 1 standard deviation from the mean.

A study conducted in 2007 by Walden, et. al., compared a self-fitted PSAP device to professionally-fitted hearing aids using measures of real-ear aided gain, audibility, and speech understanding in background noise for 32 first-time hearing aid users.8 All were self-referred, averaged 63.1 years of age (range from 39-84), and included 29 males and 3 females. Twenty-seven of the 32 were fitted binaurally. The average audiogram is shown in Figure 2.

The hearing aids were digital, multi-band/channel/memory, wide dynamic range compression circuits (WDRC) representing a variety of hearing aid manufacturers. The style was based on the diagnostic test results and each patient’s style preference. Most (38 of 59) were mini/micro BTE fittings. The remainder consisted of 4 RICs, 2 standard BTEs, and 15 custom devices. This distribution reflected the general prescription patterns for all hearing aids prescribed in the clinic.

The PSAPs provided to the participants were 16-kHz bandwidth, single-channel wide-dynamic-range-compression circuitry, and level-dependent TILL frequency response. The 2cc coupler response curves are shown in Figure 3. The device had two user-selected gain settings: 1) low, and 2) high, which were user-controlled for their hearing loss. Based on the hearing loss (unilateral or bilateral), participants were provided with one or two PSAPs, and four eartips were supplied (2 different-sized triple flange, 1 single flange, and 1 foam). The user selected the type based on trial and error, and attached the tip to the PSAP. Insertion positioning varied across users, but was based on a balance between retention and comfort. Participants used the PSAP devices for a 3 to 6-week period between the initial hearing evaluation and the initial professional hearing aid fitting.

Figure 3. PSAP 2cc coupler gain responses for inputs of 50 dB SPL (highest curve), 65 dB SPL (middle), and 80 dB SPL (lowest curve) for position 1 (LO gain, left graph) and position 2 (HI gain, right graph) conditions. The PSAPs had no other controls – neither adjustable nor programmable.

Results: Average aided gain was not significantly different between the PSAP and the prescribed hearing aids. Tested at 50 dB HL in the sound field, average audibility was 70% for the prescribed aid, 68% for the PSAP, and 57% unaided. Average speech recognition in background noise (QuickSIN) tested at 70 dB HL input was good with both devices: 2.9 dB SNR for the fitted aids and 3.8 dB SNR for the PSAP. (Normal-hearing subjects typically average 2 dB SNR.)8

Participants generally reported that the written instructions provided with the PSAP were sufficient to use the PSAP and they reported generally good subjective improvement in their hearing when using the PSAP. Dissatisfaction with the PSAP was expressed regarding cosmetics, physical comfort with extended use, and occlusion effect. The comments relative to the occlusion effect should not be surprising because the PSAPs were a closed fitting versus mostly open fittings for the hearing aids. Fitting a PSAP with an open fitting would most likely render this a non-issue. In spite of this, thirty-four percent of the participants reported they would be ‘very likely’ to continue wearing the PSAP(s).

A previous post on this site looked at consumer preference of two basic, two premium, and two PSAP hearing devices. Results showed that PSAPs performed as well in this laboratory study as hearing aids (basic and premium) for everyday noises and music, but not for speech.

OTC/PSAPs Will Cause Further Hearing Loss

A concern expressed by some is that unmanaged use of OTC/PSAPs could cause further hearing loss because they may be improperly fitted. This is based on such units having dangerous decibel levels that can present a significant risk to residual hearing in laboratory testing9. Reference was made to two reports citing high SSPL90 readings greater than 120 dB SPL in some of the units.5,7 Some legitimate questions relative to the products selected for those studies was provided in a previous report.

Regardless, further loss of hearing from hearing aid use is a legitimate concern. However, the history of hearing aid fittings, even in an era when no hearing aid had an output less than 120 dB SPL (similar to outputs in the studies cited) offers no support for this. It would be fair to say that current, better designed OTC/PSAP products have outputs more consistent with contemporary hearing aids.

A five-part series on the topic of hearing aids causing hearing loss was previously provided on this HHTM site (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5). Part of the take-away, after reviewing studies on this topic was that:

“History is on the side of hearing aids not causing additional hearing loss. If they did cause further hearing loss, research and actual utilization of hearing aids would reflect this. Millions have been fitted with hearing aids and their use does not reflect further loss. Of course, this assumes that other factors such as advancing age, medications, etc., are isolated from the impact of loud sounds.”10

User Satisfaction

A Japanese Report on The Hearing Aid Market in Japan commenting on poor customer satisfaction of OTC/PSAP products has been described as providing evidence discouraging individuals from seeking further expert help. Unsaid was that the overall customer satisfaction with hearing aids was 39%, even though 76% of sales reported were through what would be called professional dispensers (Hearing Aid Centers, Optical Shops, Hospital/Clinic).10 Additionally, as shown in Figure 4, the percent of very dissatisfied and dissatisfied was 14% for the Hearing Aid Center sales, and 17% for Internet sales. While these numbers are fairly similar, the very dissatisfied numbers were different, with Hearing Aid Center sales showing a 6% very dissatisfied to 0% for Internet sales. Internet sales of “somewhat dissatisfied” was 33% versus 19% for Hearing Aid Center sales. “Satisfied” and “very satisfied” combined showed 20% for Hearing Aid Centers and 15% for Internet sales. One can play with these percentages as one wishes, but the “devastating” results generally attributed to Internet sales seems to be somewhat subdued. True, the sample sizes were somewhat different, and could change the results, but the direction would be uncertain.

And, nowhere was data found that supports the statement that: “…the inadequate performance of such OTC hearing aids may cause wearers to decline to adopt hearing aid use” as referenced to the Japanese OTC experience as attributed to the 2015 Hong Kong study.6

Figure 4. Overall satisfaction with hearing aids as reported from sales in Japan primarily related to hearing aid centers, optical shops, and Internet sales. See text for discussion. (JapanTrak 2015).

Self-Fitting of Hearing Devices – Future Topic

OTC hearing aids assume that an individual having a mild-to-moderate hearing lose can self-fit themselves with satisfactory results. That this can occur safely and effectively has been called into question. That such self-diagnosis takes place routinely, in which the consumer decides, based on listening experiences, if their hearing is good or bad, is the bread and butter of the hearing aid industry. Individuals are mostly self-referred, based on how they assess their hearing to be. They do self-assess, and have done a rather good and significant job of this, rewarding richly the professional dispensing community. Most hearing aid sales are self-referred, meaning that the patient has made the decision that their hearing loss is great enough for them to do something about it. This topic will form the basis of a future post.

References

- Davis H., Stevens S. S., Nichols R. H., Hudgins C. V., Peterson G. E., Marquis R. J., Ross D. A. (1947). Hearing aids: An experimental study of design objectives. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- United Kingdom Medical Research Council. (1947). Medical Research Council Special Report No. 261. Hearing aids and audiometers. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office.

- Van Vliet, D. (2002). User satisfaction as a function of hearing aid technology. Paper presented at: American Auditory Society Scientific/Technology Meeting, March 14-16, Scottsdale, AZ.

- Xu J, Johnson J, Cox R. (2015). Effect of some basic and premium hearing aid technologies on non-speech sound acceptability. Poster presented at the 169th meeting of the Acoustical Society of America, Pittsburgh, PA, May.

- Internal report, non-published. PSAP devices were not identified. Referenced by Fabry at PCAST Hearing? Date, correct title.

- JapanTrak 2015. Designed and executed by Anovum (Zurich) on behalf of Japan Hearing Instruments Manufacturers Association.

- Chan ZYT and McPherson B. (2015). Over-the-Counter hearing aids: a lost decade for change. BioMed Research International, Vol. 2015, Article ID 827463, 15 pages.

- Walden, T., Walden, B., Van Summers, W., and Grant, K. (2007). Comparison of Personal Sound Amplifier Products to professionally fitted hearing aids. Army Audiology and Speech Center, Walter Reed Army Medical Center, Washington, D.C., USA. Work supported by Etymotic Research Inc., to the T.R.U.E. Research Foundation under a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement (#MA-015). Local monitoring of this study was provided by the Department of Clinical Investigation (DCI) under Work Unit #05-25020.

- Fabry D. (2017). Presentation to the Institute of Medicine (IOM)/National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine. On behalf of the Hearing Industries Association.

- Staab W. (2013). Hearing aids and further hearing loss? Part V. HHTM, October 6, 2013. https://hearinghealthmatters.org/waynesworld/2013/hearing-aids-hearing-loss-part-v/.