Baumol described a chronic economic disease of healthcare and other direct services due to service wages that must rise on the back of stalled productivity while manufacturing labor costs rise naturally on the back of increasing productivity. The result is increasingly expensive (some would say inefficient) services to administer increasingly efficient devices.

For dispensing audiologists, Baumol’s cost disease puts us loggerheads with consumers and regulators in the present market. Those stakeholders perceive hearing aid price increases as evidence of our inefficiency at best or avarice at worst. We perceive price increases as necessary and justifiable.

The cost conundrum, in Baumol’s economic view, is best handled by Plan A, namely take no action, let time and the market stay the course. He argued for Plan A because the conundrum isn’t a true problem requiring sacrifice on the part of consumers; rather, it’s a misperception by consumers of the value of money over time. Even though rising costs in the market are mirrored in increasing per capita incomes, consumers resist having to pay more at face value for goods, no matter that the goods are light years better as the result of technological innovation.

A Disease of Perception, not Economics

The cost conundrum can be recast psychoperceptually for the hearing healthcare culture in terms that are familiar to all of us licensed providers:

- We rightly perceive that our hourly wages have to go up as the annual cost of living increases.

- We know, at least in our hearts, that wage increases have to be covered by increased hourly revenues.

- We resist perceiving how our direct personal service model places severe limitations on productivity: time and service don’t change much but the price goes up regardless.

On the other side of the conundrum equation, overall wholesale cost of goods stays apace of cost of living increases even as productivity shoots through the roof. Hearing devices of increasing sophistication are produced more efficiently and at ever-expanding price points every year: time and device change alot but price not so much.

- Despite marketplace perceptions, hearing device cost is not the market villain.

- Successful providers perceive that they can control cost of goods, depending on order volume and technology level selections.

The perceptual disease lies within our traditional model, in which “product” is sold as a bundle of device+services. Retail price goes up regardless of wholesale device cost because services are bundled in. Perceptual conundrums arise, collide and cause waves in market preferences:

- Perceptually, providers understand and justify price effects based on our experience within the model. We know devices offer little or no value without our services.

- Our traditional patients cannot or will not make this perceptual distinction between device and professional personal services.

- Many consumers perceive the value of professional guided assistance for success but do not prefer to pay for it separately.

- Most consumers do not prefer to pay bigger numbers of dollars for hearing healthcare year over year, even as their own incomes are accomodating by adjusting upward.1

Neither side can or will perceptually budge and the disease goes untreated. We don’t have time to let time take its course. So much for Plan A. On to Plan B.

Treatment Plan B: Unbundled Business as Usual

Let’s assume that people continue to need and want personal services by licensed hearing professionals. So long as there is demand for our services in the market, we have a chronic but livable disease. Treatment Plan B calls for unbundling device from service in the minds of providers and consumers.

For years, many in our field have discussed ways to tease product from services in a variety of plans designed to address consumer preferences by giving them choices regarding the level and cost of services preferred. Plan Bs are usually set up with “cafeteria style” or menu pricing of service plans which range from bare bones to concierge. They are designed to attach service plans to devices sold at technology level price points.1

In addition, Windmill et al’s2 medically-grounded model weights charges according to complexity of patient encounters and Taylor describes a triage approach that could work in a similar manner. Although both return decision- making to providers, the complexity model offers consumers an intuitive grasp of resource-based pricing.

Plan B Benefits and Side-Effects

Unbundling doesn’t cure the cost disease or treat it directly. Plan B assumes the economic price/productivity disparity between services and manufactured devices is a fact of life, hence the cost disease persists in chronic form. That’s because the present service model remains intact in all ways but more transparent fee structuring. The same providers provide the same services in the same amount of time to the same patients with the same devices, although the total number of services probably declines (e.g., number of post-fitting follow-ups), depending on service plan choices made by patients a given practice. Regardless, the overriding goal of all practices that move to unbundling is to make the bottom line come out the same or better when unbundled services and device price are tallied, compared to the old bundled price.

Unbundling doesn’t cure the cost disease or treat it directly. Plan B assumes the economic price/productivity disparity between services and manufactured devices is a fact of life, hence the cost disease persists in chronic form. That’s because the present service model remains intact in all ways but more transparent fee structuring. The same providers provide the same services in the same amount of time to the same patients with the same devices, although the total number of services probably declines (e.g., number of post-fitting follow-ups), depending on service plan choices made by patients a given practice. Regardless, the overriding goal of all practices that move to unbundling is to make the bottom line come out the same or better when unbundled services and device price are tallied, compared to the old bundled price.

Unbundling would be easier and probably more effective from the get-go if we didn’t have a solid history of bundling. After years of “free” services with aid purchases, it’s little wonder that patients take our services for granted. Likewise, it’s little wonder that many are shocked, even outraged, to learn that the old bundled prices included substantial markups for (undisclosed) services. In that frame of mind, many may opt for the device-only choice on the unbundled menu and fail to return for fitting follow-up, or show up and object to paying for services that were formerly “free.”

Kick-starting Plan B is a lose-lose-lose situation: practices lose revenue, providers may lose jobs, patients get devices that may not fit or function correctly, none involved are likely to perceive relationships or trust as key components of the process.

Nevertheless, Plan B offers long haul benefits:

- Unbundling influences perceptions by bringing benefits of different kinds to various stakeholders. Consumers benefit through price transparency, which transfers some control to them and is almost always good for their pocketbooks (Tjan, 2010). 4 For providers, it opens the door for market recognition of professional services as separate but necessary and valuable components of the hearing healthcare process; we’re no longer perceived as just another button on the hearing aid.

- Unbundling redistributes resource consumption. Patients must do more due diligence when selecting treatment and pricing plans, if they want to optimize their hearing and purchase. Due diligence on the part of consumers requires education and explanation on the part of providers, which translates to higher marketing and transaction costs to sell many products compared to a single simple bundled one. In addition, sellers almost always lose bottom line4 when they unbundle, just as consumers gain, because at least marginally fewer services are demanded at the time of sale.

- Unbundling improves performance. Our bottom line can smooth out over time, so long as providers’ services are perceived by many, including 3rd party insurers, to be worth the fees charged. Convincing outcome measure data are a must, but collecting them consumes a lot of resources we haven’t allocated … yet. That’s a good problem. Being forced to get outcome measures will benefit all stakeholders in the long run, perhaps seguing us into a Plan C or D. We’ll end the post with that thought. But first, what happens if you actually implement a Plan B?

It’s One Thing to Talk About It, Another to “B” It

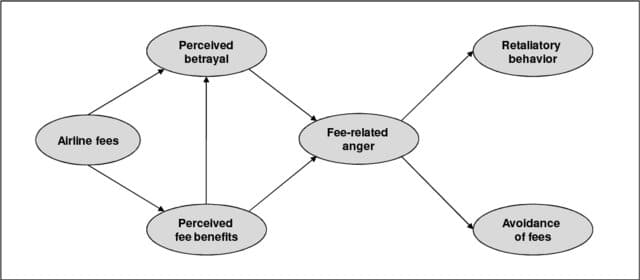

Figure 1. Consumer perceptions and reactions to airline fee unbundling (Tuzovik et al, 2011).

Baked into all Plan Bs, regardless of the menu, is a range of choices that can bewilder consumers and change on a dime. It’s the nature of unbundling, as anyone who tries to book airline tickets is aware (see Figure 1). Agony, anger and hidden costs are likely to jump out. We can only hope that retaliatory behaviors noted in the airline model don’t show up as we transition.

A few costs providers can count on are:

- cost of time spent (yes, face-to-face) explaining the myriad of plans

- time spent handling misunderstandings, which are bound to arise (consider your surprise at the airport to learn that your ticket does not qualify you for a carry-on bag)

- loss of repeat customers due to absence of supportive relationships within the practice.

Plan B is a first step. At minimum, it acknowledges the existence of the cost disease even if can’t fix it. Perceptions and other market forces won’t let us stop at Plan B, which is a good thing in the long run. We’ll have to move past palliative pricing into remedies for the disease itself. On to Plan C.

Outcome Measures Can Treat the Cost Disease

If only we knew what services benefit who and by how much at what times. That’s Plan C: to use the most efficient means at our disposal in manners that complement the varying needs of those with hearing difficulties. Plan C could tie the triage and complexity models espoused by Taylor and Windmill et al, to a data-driven model of device wearers’ preferences and performance in real world situations. As Taylor and others have framed it, Plan C would rely on data-drive measures to provide the right services to the right people at the right time.

Economically, Plan C would strive for the “no more no less” economic idea of perfect equality: consumers would get what they paid for and providers would get paid for all, but no more, than what was needed and delivered. 4 Technologically, AI, machine learning and sensors tucked into emerging hearing devices are likely to bring us close to parity. Metaphorically, the cost disease would diminish as cost of services corresponded more closely to value received. Costs could rise over time but so would consumer benefit and satisfaction for services received.

Back to those outcome measures. What might they be? What form might they take? What if they don’t demonstrate our value? What if they do? What about OTCs and self-fitted instruments?

And, ultimately: What if there’s a device-of-the-future that can do it all, or even do it better than “normal” hearing, without our assistance? Call that one Plan D.

References & Footnotes

1Although service plans can be sold as stand alones (e.g., if a patient with hearing aids transfers into the practice),

2 Windmill, IM et al. Patient Complexity Charge Matrix for Audiology Services: A New Perspective on Unbundling. Semin Hear. 2016 May; 37(2): 148–160

3 Tjan, AK. The pros and cons of bundled pricing. Harvard Business Review, Feb 26 2010.

4Ironically, Medicare is considering going to bundling to achieve this goal, even as its providers are being pushed toward unbundling.

![]() Holly Hosford-Dunn, PhD, owned and operated a dispensing audiology practice in Tucson and was active in management of HearingHealthMatters.org through 2017. She holds BA degrees in Communication Sciences, Psychology and Economics; MA in Communication Disorders; PhD in Hearing Sciences. Following post-doctoral work at Max Planck Institute (Munich, DE) and Eaton-Peabody Auditory Physiology Lab (Boston), she joined the Stanford medical school faculty as director of audiology. She has authored/edited numerous text books, chapters, journals, and articles and taught Marketing and Practice Management in a variety of academic settings. She continues to consult and write on topics related to hearing health care vis-à-vis consumer demands, professional training, technological advancement, capital investment, industry consolidation, regulatory control, product and service distribution, and strategic pricing.

Holly Hosford-Dunn, PhD, owned and operated a dispensing audiology practice in Tucson and was active in management of HearingHealthMatters.org through 2017. She holds BA degrees in Communication Sciences, Psychology and Economics; MA in Communication Disorders; PhD in Hearing Sciences. Following post-doctoral work at Max Planck Institute (Munich, DE) and Eaton-Peabody Auditory Physiology Lab (Boston), she joined the Stanford medical school faculty as director of audiology. She has authored/edited numerous text books, chapters, journals, and articles and taught Marketing and Practice Management in a variety of academic settings. She continues to consult and write on topics related to hearing health care vis-à-vis consumer demands, professional training, technological advancement, capital investment, industry consolidation, regulatory control, product and service distribution, and strategic pricing.

*Plan B image courtesy of freepik.com

A, B, C,…Z: Value-added is a perception, not an assertion.