Downstream Consequences of Aging is a bi-monthly series written by guest columnist Barbara Weinstein, PhD.

The ultimate objective of any health care partnership is to optimize the patient experience during the clinical encounter, improve patient health outcomes and ensure that patient preferences are met or exceeded (Ha & Longnecker, 2010), as discussed in Part 1 of this series. Prerequisites for a healthy collaboration during the primary care encounter include (Mauksch, Dugdale, Dodson, & Epstein, 2008):

- establishment of trust and rapport

- shared decision making

- recognition of and overcoming barriers to establishing an effective partnership.

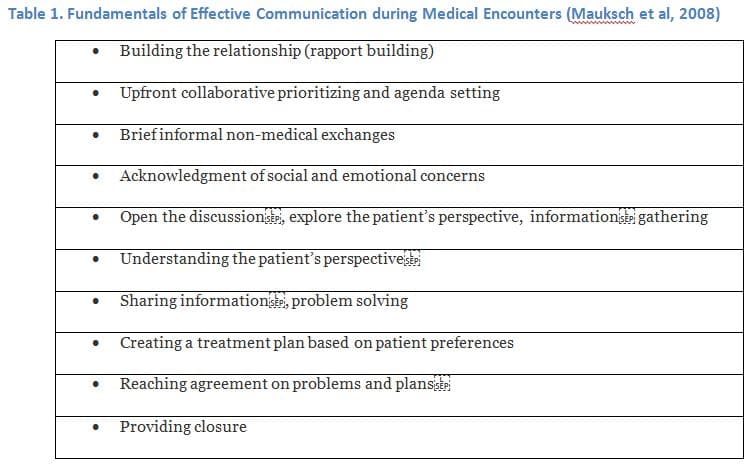

Physicians contend that it is difficult to establish rapport and provide high quality care within the limited time allotted for clinical encounters (Mauksch et al, 2008). Given the fundamental elements essential to successful communication during medical encounters namely, building of a relationship, information gathering, sharing of information, and reaching consensus on problems and treatment plans, it is evident that presence of a communication deficit on the part of the patient can impede high quality communication within the time allotted (Makoul, 2001). Physician’s assert that insufficient time allotted to meet with patients (e.g. 18 average length of primary care visits in the US) is a major obstacle to relationship development and effective communication.

My colleagues and I were curious if hearing loss is a recognized threat to effective physician patient communication (Blumenthal et al, 1999; Mauksch et al, 2008).

A Medical Disconnect

Recognizing that hearing is a first order event within the communication speech chain, we conducted a structured literature search reviewing the published medical literature on doctor-patient communication, with patients 60 years of age and older (Cohen et al, 2017). Our objectives were twofold, namely to quantify:

- the extent to which hearing loss is mentioned in studies of physician-patient communication

- the degree to which hearing loss is incorporated into the data analyses, findings, and recommendations

Despite the importance audiologists attach to the “ability to hear and understand,” of the 409 papers in the initial search, and the 67 incorporated into our systematic review, only 15 studies (22.4%) included any mention of hearing loss. Specifically:

- in five of the 15 studies only hearing loss was mentioned

- in three, hearing loss was used as an exclusion criterion

- in three, the extent of hearing loss was measured and reported for the sample, with no follow up analysis

- three studies examined or reported on an association between hearing loss and the quality of clinician-patient communication

- one study included an intervention to temporarily mitigate hearing loss to improve communication in the healthcare setting.

Three of the studies measured outcomes that would be expected to be tied to good physician-patient communication, including freedom from medication errors and participation in physical activity. None, however mentioned hearing impairment as a barrier to communication. It is noteworthy that in their systematic review examining the connection between quality-enhancing relationships, communication skills, and efficiency, Mauksch et al (2008) did not mention hearing status as a relevant variable in the equation. Yet, the ability to hear is essential to each of the skills cited as fundamental. The variables seen as critical to quality enhancing relationships in their study included collaborative agenda setting, rapport building, relationship maintenance, establishing the patient’s perspective, and co-creating a plan of action.

It is no wonder that persons with hearing loss have lower ratings of patient–physician communication and of healthcare quality than do persons without hearing loss (Mick, et al, 2014). The listening demands posed by the unfamiliar environment and the time pressure on physicians will likely impact the ability to perceive empathic cues, to remain fully engaged in decision making, treatment plan creation, and adherence with recommendations (Pichora-Fuller, 2016). Mindful of “medical paternalism,” older adults in general, and people with hearing loss in particular, are reluctant to question the authority of health care providers or the accuracy of ambiguous sensory data (Eliassen, 2016). It is also noteworthy that recall of directives from health care providers is worse when the medical information has personal relevance (aka when related to the patient’s own condition) or when the patient is vulnerable or receiving an unexpected diagnosis. Add to this, the impact of social and psychological factors which modify auditory and cognitive function to which I referred in part 1 of my post (Pichora-Fuller, 2016).

The Audiologist as Communication Advocate

In this era of collaborative health care relationships, general practitioners are trying to reinvent how they communicate with patients who increasingly are adopting an assertive yet respectful posture. Looking at the elements fundamental to communication during medical encounters which I have listed in Table 1, it is clear that hearing and understanding are essential to high quality communication (Makoul, 2001). In my view, this is where audiologists fit in to the dynamic.

Perhaps we should position ourselves as communication advocates, highlighting the important role played by hearing/speech understanding, teaching relationship centered communication in health care settings to help improve adherence, patient safety, and outcomes. In the case of the vulnerable older adult (e.g. person with hearing loss and senile dementia) we have an important role to play in clarifying how contextual factors – within the clinical setting and social factors extrinsic to the clinical setting – are moderated or mediated by hearing and communication (Street et al, 2009). Similarly, it is a clinical reality that audibility and speech understanding are critical if restoration of social roles and social engagement, ingredients of health aging, are realistic and attainable goals (Reuben & Tinetti, 2012).

Perhaps we should position ourselves as communication advocates, highlighting the important role played by hearing/speech understanding, teaching relationship centered communication in health care settings to help improve adherence, patient safety, and outcomes. In the case of the vulnerable older adult (e.g. person with hearing loss and senile dementia) we have an important role to play in clarifying how contextual factors – within the clinical setting and social factors extrinsic to the clinical setting – are moderated or mediated by hearing and communication (Street et al, 2009). Similarly, it is a clinical reality that audibility and speech understanding are critical if restoration of social roles and social engagement, ingredients of health aging, are realistic and attainable goals (Reuben & Tinetti, 2012).

Now Hear This

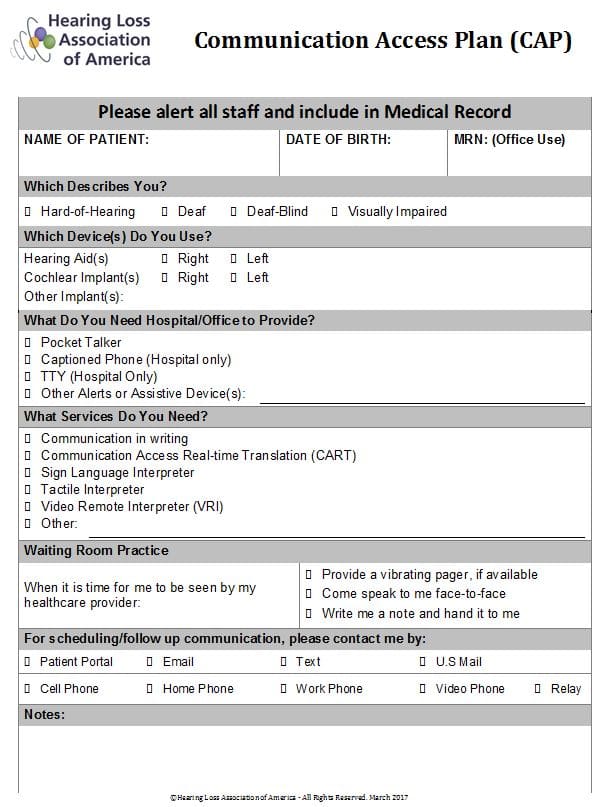

Let me conclude with one initiative to consider for those who embrace the concept of audiologist as communication advocate. Begin by making sure each patient leaves your office with a copy of the Communication Access Plan (CAP) shown in Appendix A, below.

Prepared by the New York Chapter of Hearing Loss Association of America (HLAA), the CAP is a one-page form, designed to inform doctors and members of healthcare teams about hearing status, communication aids and service needs of patients with hearing loss. Ironically, in-patients are often encouraged to leave hearing aids at home (to avoid loss or damage), which renders them vulnerable especially in the recovery room and Emergency Department (ED). This CAP is of utmost importance, as despite the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 and guidelines established by regulatory and accreditation bodies, effective communication remains a challenge in medical settings for person who are either hard-of-hearing or deaf.

Let’s work inter-professionally to gain recognition as experts on communication and as the go to resource for persons with hearing loss across the continuum of health care from acute and long term care to palliative care. Let’s begin by becoming familiar with the verbiage in the Consumer Bill of Rights and Responsibilities Act which was included in the final report of the Advisory Commission on Consumer Protection and Quality in the Health Care Industry. It states that patients have the right to receive accurate information they can understand about their health, treatments, health plan, providers, and health care facilities….(AHRQ, 1997).

Let’s work inter-professionally to gain recognition as experts on communication and as the go to resource for persons with hearing loss across the continuum of health care from acute and long term care to palliative care. Let’s begin by becoming familiar with the verbiage in the Consumer Bill of Rights and Responsibilities Act which was included in the final report of the Advisory Commission on Consumer Protection and Quality in the Health Care Industry. It states that patients have the right to receive accurate information they can understand about their health, treatments, health plan, providers, and health care facilities….(AHRQ, 1997).

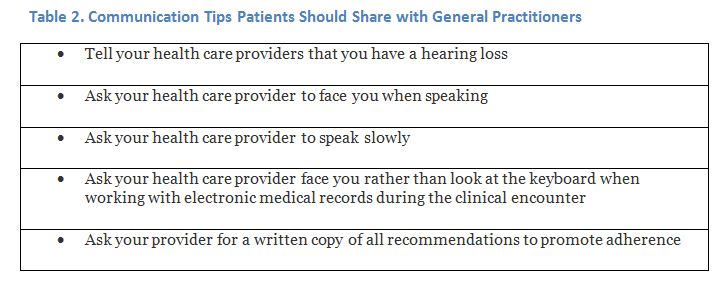

Consider sharing the tips in Table 2 with your patients. Inability to communicate effectively due to hearing loss is clearly an obstacle to realization of the Bill of Rights, so are we if we fail to advocate.

Appendix A. Sample Communication Access Plan (CAP) Reprinted with permission from Toni Iacolucci and Jody Prysock

References

AHRQ (1997). Agency for Health Care Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Consumer Bill of Rights and Responsibilities.

Blumenthal, D., Causino, N., Chang, Y., et al. (1999). The duration of ambulatory visits to physicians. J Fam Pract. 48:264-271.

Cohen, J., Blustein, J., Weinstein, B., Chodosh, J., et al., (2017). Studies of Physician-Patient Communication with Older Patients: How Often is Hearing Loss Considered? A Systematic Literature Review. Journal American Geriatrics Society. doi:10.1111/jgs.14860.

Eliassen, A. (2016). Power relations and health care communication in older adulthood: Educating Recipients and Providers. The Gerontologist. 56: 990-996.

Ha, J., Longnecker, N. (2010). Doctor–patient communication: A review. Ochsner J. 10: 38–43.

Okun, M., Rice, G. (2001). The effects of personal relevance of topic and information type on older adults’ accurate recall of written medical passages about osteoarthritis. J Aging Health. 13: 410-29

Makoul, G. Essential elements of communication in medical encounters: the Kalamazoo consensus statement. Acad Med. 2001;76(4): 390-393.

Mauksch, L., Dugdale, D., Dodson, S. & Epstein, R. (2008). Relationship, Communication, and Efficiency in the Medical Encounter. Arch Intern Med. 168:1387-1395.

Mick P, Foley DM, Lin FR. (2014). Hearing loss is associated with poorer ratings of patient-physician communication and healthcare quality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 62:2207–2209.

Pichora-Fuller, K. (2016). How Social Psychological Factors May Modulate Auditory and Cognitive Functioning During Listening. Ear and Hearing. 37: 92S–100S.

Ruben, D., & Tinetti, M. (2012). Goal-Oriented Patient Care — An Alternative Health Outcomes Paradigm. New England Journal of Medicine. 366: 777-779.

Street, R., Makoul, G., Arora, N., & Epstein, R. (2009). How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Education and Counseling. 4: 295–301

Barbara E. Weinstein, Ph.D. earned her doctorate from Columbia University, where she continued on as a faculty member and developed the Hearing Handicap Inventory with her mentor, Dr. Ira Ventry. Dr. Weinstein’s research interests range from screening, quantification of psychosocial effects of hearing loss, senile dementia, and patient reported outcomes assessment. Her passion is educating health professionals and the public about the trajectory of untreated age-related hearing loss and the importance of referral and management. The author of both editions of Geriatric Audiology, Dr. Weinstein has written numerous manuscripts and spoken worldwide on hearing loss in the elderly. Dr. Weinstein is the founding Executive Officer of Health Sciences Doctoral Programs at the Graduate Center, CUNY which included doctoral programs in public health, audiology, nursing sciences and physical therapy. She was the first Executive Officer the CUNY AuD program and is a Professor in the Doctor of Audiology program and the Ph.D. program in Speech, Language and Hearing Sciences at the Graduate Center, CUNY.

feature photo courtesy of shannon christy