A performance stage is an amazing piece of architectural and acoustic design. All locations on the stage need to be visualized from as many points in the audience as possible, and the sound level emanating from every part of the stage needs to have similar characteristics. Very soft “pianissimo” sounds need to be audible, and very loud “fortissimo” sounds needs to have sufficient clarity. A crescendo needs to be dramatic with a sufficiently long reverberation time (but not too long). There must be an excellent bass response and there must be a proper balance (or ratio) of early reflections (less than 80 msec) and those of a longer delay. And the reverberation time needs to be appropriate for the right type of music (or speech). Multi-purpose halls are extremely difficult to construct. Moveable modifications need to be incorporated as the use and type of music changes. These may include hanging reflective panels called “clouds” to help enhance certain properties of the music, as well as relatively large and dense (at least 20 kg/square meter) panels designed to reflect sufficient low frequency bass notes to yield a feeling of “warmth” and fullness to the sound. Understandably this is not always achieved despite the best attempts by the architectural and acoustical design engineers. Following is a listing a some desired reverberation times for various types of music and speech. Clearly a performance venue optimized for a symphonic repertoire would not be ideal as a lecture hall. For those who would like more information about this fascinating area check out chapter 8 by William Gastmeier in Hearing Loss in Musicians Prevention and Management edited by Marshall Chasin (Plural Publishing Inc.), 2009., ISBN-13: 978-1-59756-181-5. Actually the other 13 chapters are really interesting as well but perhaps I am a bit biased. This chart is from chapter 8.

| Desired RTs for Performance | RT (seconds) |

| Traditional organ music | 2.5-5.0 |

| Symphonic repertoire | 1.8-2.1 |

| Chamber music | 1.6-1.8 |

| Opera | 1.3-1.6 |

| Modern music | 1.1-1.7 |

| Live theatre | 0.9-1.4 |

| Lecture or conference | 0.6-1.1 |

| Broadcasting, recording studio | 0.3-0.7 |

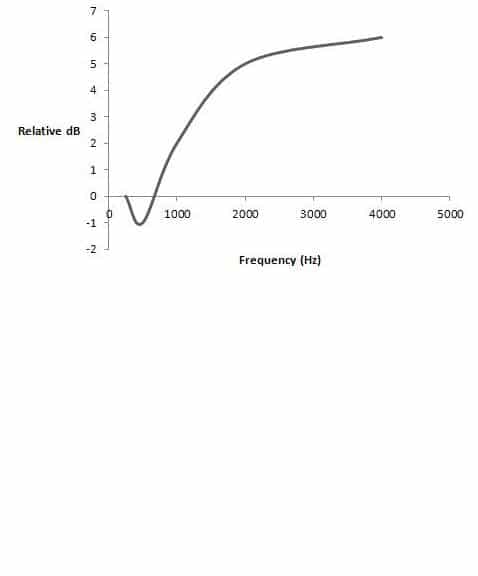

Short of being the re-incarnation of Wallace Sabine- the father of modern architectural acoustics- what can be done by the rest of us mere mortals? First, high school bands and musical groups on larger stages can benefit from “backing up”. Moving the high school band away from the lip of the stage by only 2 meters (6-7 feet for those south of the border) means that not only will the incident sound be heard, but also an “early” reflection that occurs when the incident sound reflects off the front part of the stage. Unlike “late reflections” that add to the muddiness of the sound, early reflections (<80 msec) add constructively with the incident sound thereby adding to the sound. But like the pinna effect (another form of reflection found with CIC hearing aids) the amount of reflection varies with frequency.

Moving the group back 2 meters enhances the mid- and high-frequency sounds by up to 6 dB. From a performance perspective, this means that the performer will get away with playing up to 6 dB less intense on stage while the music will still be as audible at the back of the concert hall (or school auditorium). A 6 dB reduction equates to ¼ of the exposure- the musicians can play for 4 times as long before. And because of Weber’s Law (see last week’s blog where people are relatively insensitive to changes at higher sound levels) the musicians will not find this reduction objectionable or even noticeable.

Moving the orchestra or band about 2 meters back from the lip of the stage means that musicians will not have to play as intensely in order for the music to be heard well at the back of the venue.