I have long been concerned that perhaps the musician is not the best type of research subject when it comes to assessing how a particular hearing aid algorithm or circuit may represent amplified music. Researchers, such as Dr. Nina Kraus, have spent their entire working careers trying to figure out what makes a musician tick. And ultimately the strategies used, and possibly even the structure of the musician auditory system, may not be extendable to those of us who merely play (or listen to) music.

I play several instruments but my son refers to me as a “third rate musician”- only a family member can be so honest! But he is quite correct and I have no delusions. I can read the music, perform the technical pushing of strings down on my guitar, or levers down on my clarinet, and even add some of my own flavor to the prosody of the sound, but ultimately I merely function as a machine while playing music. Even while playing jazz, I may know intellectually that we are using a II-V-I turnaround but even then I am glancing over at the piano player, notes that he is playing an F#, and I assume that we are either in the key of G or D, and then I convert to my B flat clarinet and play the in the right key… of course, by then, we are into a different key, but I may get a few bars in without hitting too many of the wrong notes. I am working hard to become a second rate musician!

This is in contrast to another (real) musician who can “feel” the music and go beyond the notes written on the page.

One may argue that it’s only a matter of practice and although that may be true, it does demonstrate that people playing music- i.e., musicians- are not necessarily the same type of creature. The same undoubtedly is true of the person listening to music. My son can hear a “dropped 4th” and an added “9th”, but I just hear the music. I may admit that it sounded different or odd but that would be the full extent of my musical analysis.

I just completed a several year study of a new hearing aid algorithm and circuit for musicians and non-musicians. Both groups fared far better with the new circuitry and I can say without reservation that hearing aids using this new circuitry will improve the ability of musicians and non-musicians to perceive and enjoy music. But the musician group fared much better than the non-musician group.

This is not a new finding. For a wide range of tasks- musical or otherwise- musicians perform better than non-musicians. It does however, make one wonder whether using musicians as subjects will bias the results. Like my musician son, musicians hear things that we mere mortals don’t.

And this is further complicated by a further division of musicians into sight readers vs. those who play by ear – guess which category I fall in to?

This question was posed by Eriko Aiba, an assistant professor in the Graduate School of Informatics and Engineering at the University of Electro-Communications in Tokyo, Japan and reported at a recent Acoustical Society of America meeting. The article was entitled How do musician’s brain work while playing?

In this study Dr. Aiba found that “some were able to memorize almost the entirety of two pages of a complex musical score — despite only 20 minutes of practice.” This means that auditory memory may be helpful for memorizing music following short-term practice.

And auditory memory has been implicated in a wide range of tasks from learning a new language, to hearing in noise. Some can simply fill in the blanks better than others and are more accepting of background noise levels. People who have excellent auditory memories- either naturally or through training/therapy- receive and maintain information that others cannot.

In this recent study that I performed, the improvements were the largest for musicians when old and new technologies were compared. There were still very large improvements even for the non-musicians though not quite as much.

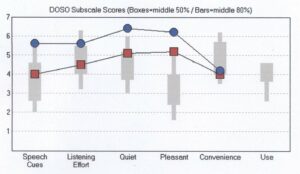

The following graph is one result on my 20 subjects- ten of whom were non-musicians (red squares) and ten of whom were musicians (blue circles). Both groups did significantly better with the new technology but the musician group did much better. These data were compiled from the Device-Oriented Subjective Outcome (DOSO) Scale by Robyn Cox and her colleagues (2014).

Differences between Musicians and Non-Musicians using the DOSO with new hearing aid technology. (From Chasin, 2017, in press).

I am not sure that I am just being silly by questioning whether musicians have an unfair advantage when it comes to blinded research- it’s not as if non-musicians in this study did not perform significantly better with the new technology and I am just “hiding” this fact from the peer reviewers. Both groups did significantly better; just one group did really quite well.

I imagine the musician (or sound engineer) would be able to provide better feedback (excuse the pun) when tweaking the instrument. Or is this strictly a “fit first time” kind of thing?

Also, what fitting algorithm is recommended for a male mid-50’s with some audio knowledge. I understand there are new ones that are geared to this age demographic, but for the life of me I cannot find what it’s called. Pretty sure I read about it on HHM a few years back.

The fitting algorithm depends on many factors, including a frequency by frequency assessment of gain and of output. I wouldn’t suggest doing this yourself- best to chat with your audiologist. There are no age-associated fitting formulae nor valid ones that are for speech vs. music. By the time a child is 3 or 4, the earcanal has grown to almost adult size so that Boyle’s Law effects are the same as an adults.