by Kathi Mestayer

People with hearing loss can be tough to accommodate. Sometimes, we wear our hearing aids, sometimes not. Sometimes, we nod and smile when we know we didn’t hear you. Sometimes, we just don’t know we didn’t hear you.

This is challenging in healthcare situations.

I’ve been there more than once: in the hospital, emergency room, imaging facilities, doctors’ offices and pharmacies. The problems are not that different from my everyday communication struggles with mumbling, background noise, reverberation, plus the stuff I bring to the table – the need for better volume, clarity and maybe…repetition? …talk slower? But in healthcare settings, the stakes are a bit higher than not hearing the cashier ask if you want paper or plastic bags.

Stepping up to the plate

We recently made a trip to the Emergency Room with my father, a cochlear implant wearer, who had slipped and hit his head against a brick wall. (In case you’re wondering, he was fine; he’s always been hard-headed.) He arrived in an ambulance, and my stepmother, Mary, and I arrived moments later, through the main door.

We walked up to the receptionist, and told her that we were with him. She asked us to go to the waiting area until we were called. It was tense because Mary and I knew, but weren’t sure the staff was fully aware of, that Dad would have a really hard time hearing anything they said to him, given his hearing loss, which would be exacerbated by the added stress and chaos of the ER.

After about three minutes, Mary stood up and calmly strode into the ER, right through the big double doors, like she owned the place. I just watched, amazed once again at her chutzpah. Then, about ten minutes later, I surreptitiously peeked through the doors, and saw her and Dad in one of the examination rooms. I joined them, trying to melt into the background to observe.

It was very clear that, if Mary hadn’t been there, communication between my father and the medical staff would have been impaired, to put it mildly. It’s hard for me to imagine how they would have gotten through the ER visit without her curating.

It’s so easy for people to forget to face someone, let alone talk slowly and loudly, without distorting the speech sounds, or to take out a pad and pencil and write it down to make sure your point is getting across correctly. ER staff have a lot on their minds, and adapting to a patient with hearing loss adds weight to that cognitive load.

Fortunately, we were able to bring Dad home with us that night, so we were all back in familiar surroundings when it was time for coffee the next morning.

The dreaded intercom system

Sometimes, hospital communication systems just don’t work for the hard-of-hearing. After a recent surgery, I was in the recovery room, waiting for the doctor to come in and tell me how it went. All of a sudden, a loud beep sounded from somewhere near my head. I reached around and found the handset for the intercom system, and it beeped again. This time, a voice came on, asking or telling me something that I couldn’t understand. So, I just said, “I can’t hear you.” And within a few minutes, a nurse appeared in my room.

It doesn’t always work that way, though. A cochlear-implant-wearing friend, just out of surgery, repeatedly tried to call a nurse by pressing the intercom button. In response, the nurse on duty used the intercom to ask him what he needed. Which he didn’t hear. That went on for three or four iterations, until he gave up and shouted loudly enough to get someone to come down the hall to his room.

And then there’s the acoustics

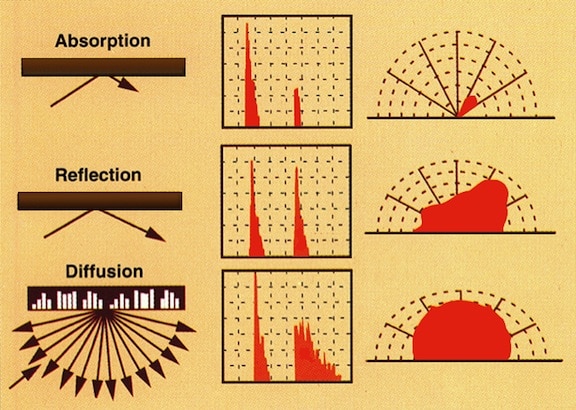

Same hospital, a few weeks later. I’m in the registration area, reporting for something. It seems kind of loud, even though I can’t hear or see anyone talking. So, I boot up the decibel meter app (AudioTools) on my cellphone and measure the background noise. It’s 50 decibels, and that’s just the hum of the HVAC system!

Typical conversation is about 60 dB, so the background hum isn’t quite as much of a barrier as people talking nearby, but it’s a pretty high baseline. So communicating in that space is harder than the hospital, or its designers, might think.

Doing it right

Finally, a shout-out to my doctor, who knows I’m hard-of-hearing, and communicates with me in a way that works. When we have an appointment, she pulls her chair right up to mine, looks me in the eye, and focuses intently on what we are saying to each other. My stress level goes down by half, just by cutting out the effort of understanding, and being able to focus on the business at hand.

Sometimes, technology isn’t available, or presents barriers to communicating, like the intercom system. But, at other times, it ain’t rocket science…just paying attention and listening will do the trick.

Kathi Mestayer writes for Hearing Health Magazine, Be Hear Now on BeaconReader.com, and serves on the Board of the Virginia Department for the Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing. In this photo she is using her iPhone with a neckloop, audio jack, and t-coils which connects her to FaceTime, VoiceOver, turn-by-turn navigation, stereo music and movies, and output from third party apps, including games, audiobooks, and educational programs.

Kathi Mestayer writes for Hearing Health Magazine, Be Hear Now on BeaconReader.com, and serves on the Board of the Virginia Department for the Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing. In this photo she is using her iPhone with a neckloop, audio jack, and t-coils which connects her to FaceTime, VoiceOver, turn-by-turn navigation, stereo music and movies, and output from third party apps, including games, audiobooks, and educational programs.

I have had similar problems. I have developed a one-page check list for both hospitals and patients re access. If you send me an email address send it as attachment.

[email protected]

I just sent Gael Hannan a copy.

You ask, “please speak a little louder (don’t scream) and more slowly” and this accommodation last 5 seconds. People think we have lost our minds or cannot understand our native language English. It is a tough life out there but always take a hearing person with you to the hospital. Since my family is 1000 miles away and I am 80 years old I may get an Ohio Patient Advocate. Thanks for this fantastic article.