Phonemes, visemes and homophenes. Try saying that 10 times real fast. Really – try it!

If you’re like me, after the second repetition, it comes out all jumbled. Which is very ironic for people with hearing loss because these three terms relate to issues of speechreading, which all of us do to some degree in order to understand the spoken word.

I can’t explain these terms any better than descriptions in Wikipedia:

A phoneme (/ˈfoʊniːm/) is one of the units of sound that distinguish one word from another in a particular language. /pit/ and /pik/ differ by one phoneme and refer to different concepts. Spoken English has about 44 phonemes.

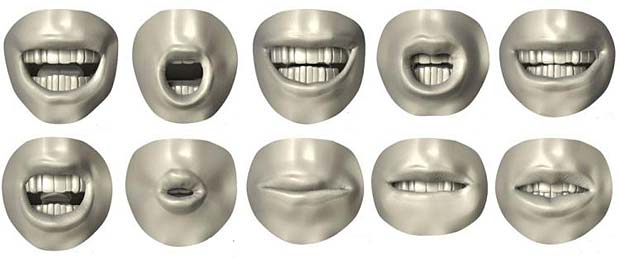

A viseme is a visually distinctive unit that helps with lipreading, and there are fewer visemes than phonemes, which map on to the visemes to create speech. Many phonemes are produced within the mouth and throat, and cannot be seen. So, voiced and unvoiced pairs look identical, such as P (unvoiced) and /B/M (voiced); and F (unvoiced) and V (voiced).

Homophenes are words that look the same on the lips, but contain different phonemes and have vastly different meanings. Examples: mean/bean and mat/pat/bat.

Because there are about three times as many phonemes as visemes in English, it is estimated that only 30% of speech can be speech-read. The percentage of comprehension rises vastly when facial expression, body language and context are factored in. Using the mat/pat/bat example, if we’ve been talking about baseball, and you’re doing a lot of eyeball rolling, I would guess that you said ‘bat’, as in the team’s worst hitter was coming up to bat. If you’re complaining about the kids tracking in dirt, you’re clearly not talking about pat or bat – you’re raging about the mat that the kids don’t use!

If you are in close communication with someone who has hearing loss, it helps to understand these simple fundamentals of speech and speechreading. In noisy group conversations with overlapping voices, it’s hard for us to follow the flow of conversation – by the time we turn our head to the next speaker, we’ve missed half of what s/he said because we didn’t see it and then, OMG, someone else starts speaking and we have to locate the source of noise, and on and on it goes. By the time we jump in with a comment, we’re embarrassed to discover that, apparently, we’re not talking about that anymore, we’re talking about this!

This is why people with hearing loss often sit back during a group conversation, put a little bluffing smile on their face, and start replaying last night’s Netflix show in their head.

Whether it’s a group convo or a one-on-one chat, there are a few things that can help everyone to ‘give good lip’ so that speechreaders like me can understand you. Some are basic, others require a little more effort.

- Get our attention before starting to speak.

- Face us.

- Speak clearly, at a moderate pace and don’t over-enunciate or yell.

- Repeat what you said, if asked.

- One person speaks at a time: this is the lofty goal for conversations involving people with hearing issues, but unfortunately it seems to be as elusive as the Holy Grail. Putting up your hand before speaking is a good try, but likely to get lost in the fast flow of group dynamics. Try a ‘talking stick’; it might slow the conversation down, but it will be clear to everyone. If that doesn’t work, speakers can help us keep up with the flow by pointing at who’s speaking. The person with hearing loss should be proactive in working out a system with the group.

Don’t get all hung up on phonemes, visemes and homophenes. Just use the simple guidelines and use your face is a goldmine, a treasure chest, a jackpot of information for us. Use it and you’ll be giving good lip!

Photo: Preston Blair Phoneme series

I’m late deafened bilaterally at age 55 so I just happen to be one of those folks that would walk to the moon and back to have my normal hearing returned to me. Back to normal as they say. . It went from “normal” ( I think it was) to nothing in either ear over a period of six months.

What I wanted to add to this section that Gael spoke about is, the fact that I feel I am so good and even maybe bordering on outstanding at reading peoples facial expressions and emotions. I really do an excellent job of that. Something that adds to how the speaker is truly feeling at the time they are speaking or even being silent.

Prior to hearing loss I didn’t bother to pay any attention to any facial expressions. Sometimes people do not even need to say a word and I can understand how they are truly feeling regardless of what they say. Or don’t say. So there’s that.