by Abha Sharma

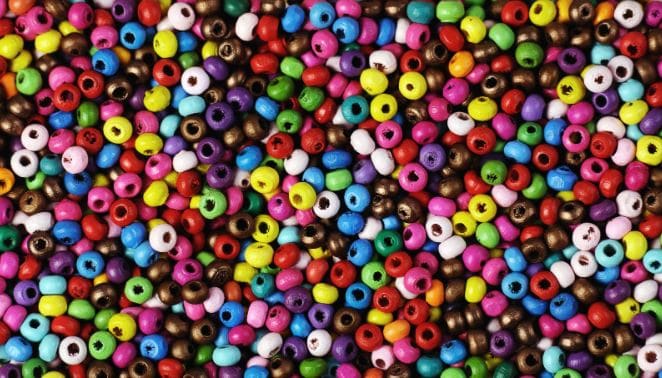

There is no first memory of the barter beads. But they were the constant buddies in my school bag. A fistful or so was all that was needed.

The protocol was simple: a casual remark, and my list of questions on the classes, preceded or followed by an offer of beads. Colorful beads!

“Can I ask you something? Oh, I have those beads for you. Let me go get them first.”

“Do you like beads? You do? I can get yellow beads tomorrow. By the way, what did teacher say at the end of class today?”

First grade was a big classroom, too big for my liking. Surrounded by a verandah, it opened to grounds with small, uneven grassy, imaginary hillocks for our mid-morning recess. Thirty minutes was long enough to snack on our tiffinsand play a bit.

If you were quick, you could even snag a couple of rides on the metal swing or join in the telephone game where everyone sat down in a circle and someone whispered a word into the ear of their neighbor. The game continued as each one of us relayed the softly mouthed word until the last player revealed it to the entire group, evoking laughter and witty comments. The whispered word was a perpetual mystery to me. Nevertheless, I participated. Pretense was easier.

The swing was my favorite. A narrow wooden slat hung with strong twisted ropes from a metal contraption in the gardens. I could bend down to Mother Earth and pump and pump and then build up momentum to go faster and faster, high up to the blue skies. Mostly alone, sometimes, I shared with a friend. With just the wind in our faces, I need not hear anyone on the swing.

Recess at school was dear to me, but for reasons other than eating and playing. A few quick bites of my tiffin—jam sandwiches and water guzzled from a colorful bottle—and I was ready with my list.

If I was lucky, I was already next to someone smart and helpful. If not, I must decide where to look for a kind classmate. I certainly could not exasperate the same person daily. Over time, I had learned that.

What I never could learn was the name of my teacher. Let’s call her Miss Kumar. She was nice but I missed Miss Rose, the kindergarten teacher. Time and again, she pointed to each alphabet and number on the charts with her long wand-like wooden ruler. Loud and clear, learning was always easy with her. I never wanted to leave her class. I never had a list with Miss Rose.

My list was long: the ‘strange-sounding mumbles’, ‘new words’, ‘words that Miss Kumar spoke with her back to us’ and ‘perceived announcements’. On a good day, I might get lucky. All questions on my list were answered before the bell rang for the next class. On a difficult day, I memorized the list or wrote them down on a sheet. Tomorrow was another day.

The classroom had a big board at the front. Black, all over, in a brown wooden frame. The white chalk words glistened on the black, nice and clear. I liked to read them all. It was also nice to be called out to come up and clean the board. I liked doing that. The chalky duster sprayed mists of white when I beat the duster on the walls outside. I liked that even more. It was a break from a continual comprehension of spoken words.

What I did not like was when Miss Kumar turned her back to us. Her right-hand held the white chalk, writing rapidly; her lips spoke words definitely not in sync with the written stuff. And then sometimes, without warning, she would even begin to ask questions. Just like that. I would look up to several faces staring at me. Clueless, I would wonder until Miss Kumar turned to face the class. Sometimes, she repeated her question. Other times, she questioned my attention span.

The English lesson began well enough. I was comforted to see Miss Kumar seated at the front, distressed when she walked the aisles between desks. One by one, we all had to read two or three lines. Sitting as we were in twosomes, tracking was not hard. As soon as my desk-mate finished, I knew where to begin. Sometimes, however, Miss Kumar played games and randomly selected the next reader. Anxious, my finger atop each word, I yearned to begin right.

Senior classrooms were housed in another building, the fourth grade being the pinnacle of this exclusive English medium school. Intimidated, I dreaded the promotion. Of course, Mother disagreed with me. She thought I would be just fine. I was.

Fourth grade, with two pairs of open doors and windows on opposite walls, was a breezy classroom where most words whooshed away. Single-seater desks and the teacher’s privilege to seat the forty-plus students did nothing to help assuage my mounting fears. Plus, I had shot up three inches and was relegated to the back bench. Each word spoken by the rambling teacher had its own ring, each sound its own spelling, at least to my ears.

Etched sharply in my memory is the single water tap located in the grounds behind the building. That was my haven. During recess, everyone gathered and filed in a long queue, waiting to fill up their water bottles. Time and again, I quietly emptied my filled water bottle into nearby bushes for another chance to join the queue. Sometimes, it was outside the rickety, squeaky wooden door of the restroom where my listed queries found their replies.

In the end, I survived the fourth grade well enough, sans the colorful beads. Perhaps they were exhausted or no longer charmed my classmates. Certainly, they did not accompany me as I progressed to the next class, blissfully unaware that I was deaf.

Abha Sharma is a research scientist at the Department of Bioengineering at the University of Washington, Seattle. A self-taught lip reader who struggled to hear since childhood, she was diagnosed with bi-lateral moderate to profound sensorineural hearing loss only in her early teenage years. Staunch support from her parents, especially her father, enabled her to complete college with a strong academic background and a Ph. D in Biophysics from the premier All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) in India. Abha is married to Rajendra. Together with their two children, they traversed a tough immigration process to Texas in 2000 before relocating to Seattle. Her passions include dancing, writing, painting, cooking and exploring ancient alternative therapies including water.

Abha Sharma is a research scientist at the Department of Bioengineering at the University of Washington, Seattle. A self-taught lip reader who struggled to hear since childhood, she was diagnosed with bi-lateral moderate to profound sensorineural hearing loss only in her early teenage years. Staunch support from her parents, especially her father, enabled her to complete college with a strong academic background and a Ph. D in Biophysics from the premier All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) in India. Abha is married to Rajendra. Together with their two children, they traversed a tough immigration process to Texas in 2000 before relocating to Seattle. Her passions include dancing, writing, painting, cooking and exploring ancient alternative therapies including water.

A beautifully crafted story, woven with the reality of a bright accomplished writer and her experience as a child with hearing loss in the main stream school. Hearing loss gave me some precious gifts. First my second son who is deaf and at this point in my life a great friend Abha Sharma. Congratulations my dearest friend. Also I like to congratulate Gael Hannan for your accomplishments and most of all for your advocacy. Good health and much success to both of you!

Thank you for all your wonderful comments about Abha’s heart-rending story and my work.

Thank you -Angeliki.

Mainstream schooling for children with hearing loss or the deaf can be hard but possible. It certainly requires more patience, empathy and careful observation from parents and teachers in addition to improvised methods for teaching in a mixed classroom.

Thank you so much-Angeliki. I am blessed to know you.

You described my elementary school experience to a “t”. (Though I did not think of barter beads.) I hope that parents who have children with hearing loss and teachers see your essay. Thank you for sharing it with us.

You’re welcome, Charlea – thanks for posting your comments.

Thank you for your kind words, Charlea. This means a lot to me. People find it hard to imagine that a child will remember things like these but its the truth.

Thank you, Charlea. Yes, it is my hope that parents and teachers will become more aware of this possibility when dealing with children who appear to be lost and non-attentive.

Young children have no way of knowing what and how normal is “normal hearing”.

Abhaji your repertoire of creativity is unending. You have so beautifully and gently expressed the auditory challenge here .Your courage and resilience showed right from that young age. I extend my best wishes for this writing, and hope for many more to come.

This story also speaks for me, that could have been me any day at school.

I remember one of the things I hated the most was the spelling quizzes, I could never get them right.

I was not aware I had hearing loss until I went to college when I realized I was not hearing like

the other classmates.

Wow, the way you took me on the journey of your experience of grade school, was eye opening. What I admired most was that while I was feeling sad about your experience, the tone of the story was one of perseverance and not sadness.

Love all your stories. Thank you. Miss you. Here’s to getting back to something normal and more of your humour. Congrats. Xoxomip.

Beautiful story, Abha Sharma. Those of us with childhood and teenage hearing loss can all identify!