Diagnosing episodic dizziness can be challenging as most patients are asymptomatic when they arrive for examination. Episodes of dizziness can be broken down into two broad categories based on two variables:

- Triggered vs. Spontaneous episodes

- Episodes of less than five minutes duration or more than five minutes duration.

Fortunately, these categories align in that most short duration dizziness is triggered, and most long duration dizziness is spontaneous.

The vast majority of patients complaining of episodic dizziness are suffering from just a handful of possible pathologies. Study after study on epidemiology of episodic dizziness finds that, usually in this order, the most common causes of episodic dizziness are Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV) and migraine, followed by orthostatic hypotension (OH) and Meniere’s disease.

“When it comes to dizziness, it is my belief that Meniere’s disease is frequently over-diagnosed and migraine is often under-diagnosed.”

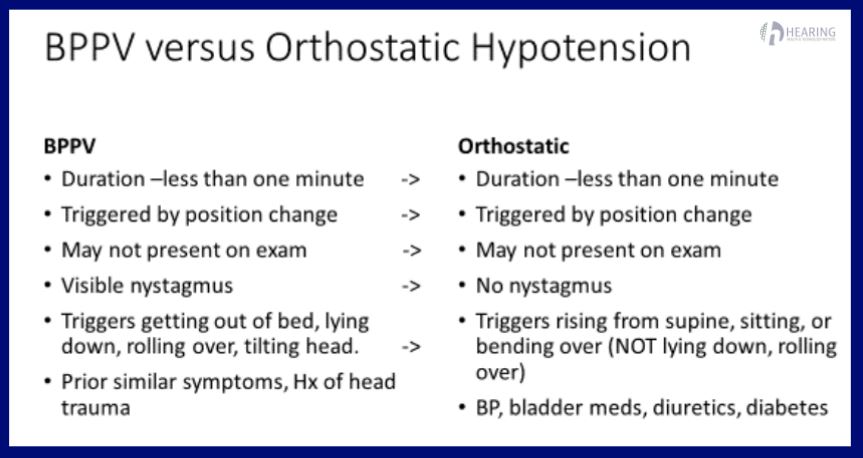

BPPV and OH have overlapping triggers and duration. Basically, “if I make the wrong move, I get dizzy for less than one minute”. Many patients will report the symptoms lasting “a few minutes.” In differentiating BPPV from OH, let’s look at what is similar and what is different. Both are triggered by position change, symptoms typically last less than a minute, and cannot reliably be reproduced on exam. If you can trigger an episode of positional vertigo, or document a drop in blood pressure on standing, it’s easy to make the diagnosis.

Distinguishing between BPPV and Orthostatic Hypotension

The main difference between the two is the trigger. BPPV can make you dizzy when you get up from bed, but OH will NOT trigger symptoms by lying down or rolling over. Ask the question “Does this happen when you lay down or roll over in bed? If the answer is “Yes”, OH is very unlikely. Sometimes, just looking at the patients medications can increase your suspicion of OH.

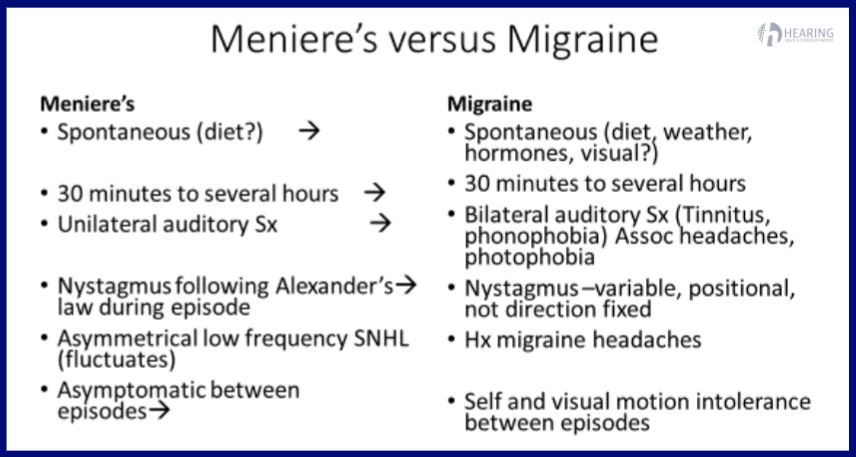

Distinguishing between Meniere’s and migraine can be difficult. There is no specific test for either, and the diagnosis is based on recurrent transient symptoms. Because these two conditions are generally poorly understood, many people with migraine have historically been incorrectly diagnosed with Meniere’s.

Is it Meniere’s disease or migraine?

A quick and reasonably accurate way to identify these patients is to simply ask, “In which ear do you have Meniere’s disease?” Patients that truly have Meniere’s have little difficulty answering that question, so if they are not sure which ear is affected you may want to accept that diagnosis with caution.

Both Meniere’s and migraine patients mostly perceive attacks as spontaneous. The duration and vertigo/nausea symptoms are similar. In Meniere’s, associated tinnitus is unilateral (one ear). Migraine patients may report increase tinnitus with episodes, but the tinnitus is usually bilateral (both ears). If you see them during an attack (which is rare) Meniere’s will have visible nystagmus following Alexander’s law. Migraine patients may have nystagmus, but it is usually minimal. Patients can video their eyes during an episode with a smartphone.

Meniere’s patients are typically asymptomatic in regards to vestibular symptoms between episodes, whereas migraineurs are often sensitive to motion and external visual motion.

An audiogram is the best method of separating the two. Low frequency unilateral sensorineural hearing loss (LFSNHL) is very rare in migraine, and it’s very rare that a Meniere’s patients does not eventually have LFSNHL.

In the early stages, there may be no measurable hearing loss between episodes in Meniere’s, but it makes sense to get an audiogram (hearing test) as a baseline, then monitor any changes over time. It may be a scheduling headache, but you ideally want the audiograms done both when the patient is symptomatic, and on a good hearing day to document fluctuations.