Most vestibular disorders cannot be diagnosed by testing alone. With the exception of BPPV, patient’s test findings must be placed in context with the medical history and symptoms. Some common disorders, such as vestibular migraine, suffer from no diagnostic tests, and diagnosis is primarily based on patient report of symptoms.

Financial pressures which affect both generalists and specialists alike, have resulted in shorter appointment times with patients. In the 1970s the average face-to-face patient visit time was approximately 45 minutes. As of 2004, the average patient time decreased to 15 minutes.

Importance of Case History in Vestibular Clinic

These competing challenges require both efficient and in-depth history taking when evaluating a patient complaining of dizziness of vertigo. Patients often have difficulty in articulating their symptoms, and most are unaware of what information is relevant to narrowing down differential diagnosis. This leaves the examiner responsible for determining whether the history interview should be directed or open-ended.

An argument could be made for both approaches, so the examiner must handle each patient individually and uniquely.

In primary care, achieving a firm diagnosis in the patient complaining of vertigo or dizziness is unlikely as a result of reduced time, training, or available diagnostic testing.

The goal of initial primary care examination may be broken down to attempting to answer a few simple questions:

- “Is this a worrisome or benign condition causing this patient’s complaints?”

- “is this an otologic, neurologic, or cardiologic condition?”

- “Does this patient need specialty consultation or not?”

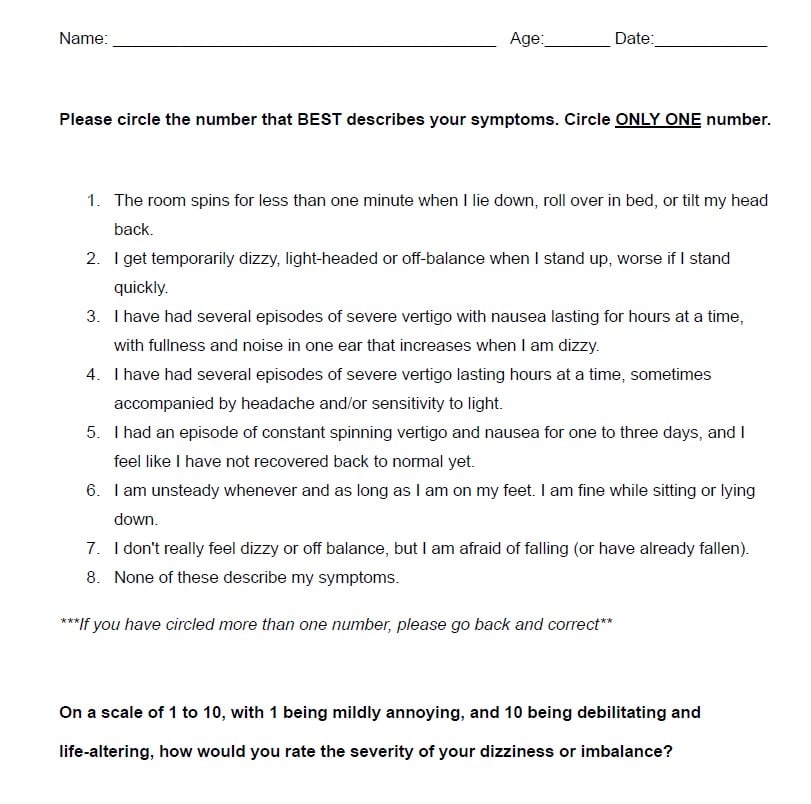

For this type of patient, a directed questionnaire can significantly reduce time and increase efficiency. For an example of this I have attached a copy of our Short Form Questionnaire (SFQ) at the end of this blog.

For this type of patient, a directed questionnaire can significantly reduce time and increase efficiency. For an example of this I have attached a copy of our Short Form Questionnaire (SFQ) at the end of this blog.

In the specialty setting, directed questionnaires can serve as a starting point, and for some disorders may provide sufficient context and direction for vestibular function testing. Where directed questionnaires fail is in understanding the quality of life and emotional impact. This can be formally assessed by using tools such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scales (HADS), the Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI) and/or the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36). You can also allow the patient to describe, in detail, their concerns.

“Directed questionnaires can serve as a starting point for vestibular function testing, but they often fall short in capturing quality of life and emotional impact. Formal tools like the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scales (HADS), the Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI), and the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) can provide deeper insights.”

Many reports have demonstrated that practitioners often interrupt patients as they describe their symptoms and concerns. One recent study reports that patients are interrupted nine times per minute as they describe their concerns. Sometime these interruptions encourage the patient to provide more detail, but some change the subject and stop the patient from completing their thought.

No ‘One Size Fits All’ Approach

Any seasoned practitioner will identify with, or can relate their own experiences with patients that have a determined narrative, and seem to be unwilling or unable to answer specific questions. Some patients get upset when you want more detail than, “I’m dizzy.” Some want to tell you what they think is causing the symptoms before describing the symptoms. Some are convinced that they have the same thing their neighbor had. The list goes on.

The point of this blog is that there are many approaches to taking a history, there is no “one size fits all” approach, and it takes a while to develop this skill.

About the author

Alan Desmond, AuD, is the director of the Balance Disorders Program at Wake Forest Baptist Health Center, and holds an adjunct assistant professor faculty position at the Wake Forest School of Medicine. He has written several books and book chapters on balance disorders and vestibular function. He is the co-author of the Clinical Practice Guideline for Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV). In 2015, he was the recipient of the President’s Award from the American Academy of Audiology.

Alan Desmond, AuD, is the director of the Balance Disorders Program at Wake Forest Baptist Health Center, and holds an adjunct assistant professor faculty position at the Wake Forest School of Medicine. He has written several books and book chapters on balance disorders and vestibular function. He is the co-author of the Clinical Practice Guideline for Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV). In 2015, he was the recipient of the President’s Award from the American Academy of Audiology.