Symptomatically, Vestibular Neuritis (VN) typically presents as sudden onset spontaneous acute vertigo, often associated with nausea and vomiting. The vertigo typically lasts for a minimum of several hours to sometimes days. While the intensity of the symptoms can be exacerbated by movement, they are not resolved by lying or sitting still in the first 24 hours, which differentiates VN from the most common cause of vertigo, BPPV (benign paroxysmal positional vertigo).

The intensity of the vertigo during this acute phase tends to decrease over a 12 to 72-hour window, with minimal symptoms while stationary by the second or third day. Most patients then enter a chronic phase where they are asymptomatic if stationary with eyes fixed on an object. Once they start moving around, they feel unsteady and may notice visual blurring with head movement, a condition known as oscillopsia.

Because the inner ear is not registering movement correctly, patients predictably become more dependent on visual and tactile information for balance and orientation.

Inner Ear Anatomy

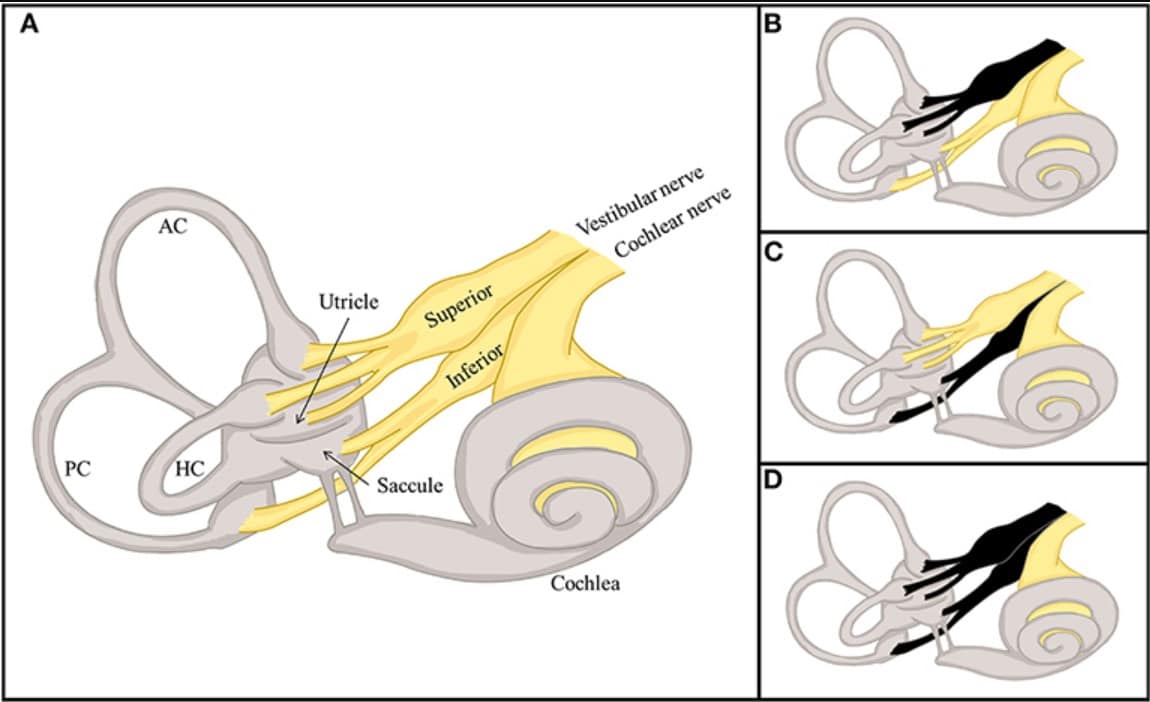

The inner ear consists of a Cochlea and a Labyrinth. The Cochlea is responsible for hearing, while the Labyrinth is responsible for sensing movement and position. The inner ear is connected to the brain by the VIIIth cranial nerve (also known as the vestibulocochlear nerve), which has three branches.

The cochlear branch of the nerve transmits hearing information. The superior portion of the vestibular nerve primarily transfers information about horizontal head movement, while the inferior portion of the vestibular nerve primarily transfers information about vertical head movement.

Divisional structure of the labyrinth and the three distinct types of vestibular neuritis (VN). (A) The vestibular labyrinth is divided into superior and inferior sections. The superior division includes the anterior (AC) and horizontal semicircular canals (HC), along with the utricle and their afferents, while the inferior division consists of the posterior semicircular canal (PC), the saccule, and their afferents. (B–D) Based on the affected division, VN is categorized into three types: superior (B), inferior (C), and total (D). Credit: Kim, J.S., Frontiers in Neurology

What Causes Vestibular Neuritis?

Vestibular neuritis is believed to be a result of viral inflammation and swelling of the vestibular nerve which connects the inner ear to the brain. The swelling causes compression of the nerve where it passes through a narrow bony opening through the skull. This compression disrupts nerve transmission and blood flow. The result of a sudden disruption of nerve transmission from one inner ear is that the brain is receiving asymmetrical inputs related to movement. This asymmetrical input subjectively simulates a sense of constant rotation (vertigo), which leads to imbalance, nausea, and frequently vomiting.

As noted, this compression of the nerve disrupts vascular supply which can lead to permanent damage to the affected vestibular nerve. This permanent damage results in a chronic weakness of the affected ear’s ability to sense movement leading to potentially chronic symptoms associated with the vestibular ocular reflex (VOR) deficit. The VOR is primarily responsible for visual stability with head movement.

Vestibular Neuritis can affect one or both branches of the vestibular nerve. If the third branch of the VIIIth cranial nerve (the cochlear branch) is involved, then hearing is also affected and the condition is termed Labyrinthitis. Because a small stroke of the artery that feeds the inner ear can cause symptoms indistinguishable from Labyrinthitis, if sudden onset hearing loss accompanies the vertigo, testing to rule out stroke is recommended.

Examination –Acute Phase

Due to the sudden onset, severity of symptoms, and acute nature of VN, most patients are first evaluated in the Emergency Department or an Urgent Care facility. There are guidelines in place to assist first line physicians and practitioners (GRACE-3 Dizziness – Emergency Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline) on how to best determine if a patient with acute vertigo is experiencing VN, versus something more worrisome (e.g. stroke). The guideline recommends the use of a test protocol known as HINTS (Head Impulse, Nystagmus, Test of Skew).

Most patients with VN have visible Nystagmus (jerking involuntary eye movements) in the first 24 hours, but these become less visible over a few days. Nearly all patients with recent onset VN will have a positive Head Impulse test when the head is moved quickly towards the affected side. This means that the eye cannot stay stable on a target when the head is moved quickly.

Most patients with VN have visible Nystagmus (jerking involuntary eye movements) in the first 24 hours, but these become less visible over a few days. Nearly all patients with recent onset VN will have a positive Head Impulse test when the head is moved quickly towards the affected side. This means that the eye cannot stay stable on a target when the head is moved quickly.

Vertical diplopia (double vision due to vertical misalignment of the eyes, known as Skew Deviation) is not a symptom of VN, so if this is noticed on examination, more worrisome causes of vertigo such a stroke are suspected.

Treatment –Acute Phase

Treatment during the first few days is focused on minimizing symptoms and potential for permanent damage to the vestibular nerve and/or inner ear. Anti-nausea drugs such as Meclizine (Antivert), Zofran, Phenergan, or sedatives such as Valium can reduce the nausea associated with acute, ongoing vertigo.

High dose steroids delivered either orally, intravenously, or injected through the eardrum have been shown to reduce swelling of the vestibular nerve and reduce permanent damage to the inner ear when administered during the acute phase, preferably within the first 24 hours.

Examination – Chronic Phase

Once the acute phase has passed, usually a matter of days, not weeks, some patients recover fully with no residual symptoms or measurable deficits. Many patients have lingering, sometimes permanent symptoms if the inner ear suffered any permanent damage during the acute phase.

Chronic symptoms can include visual blurring or visual instability with head movement, usually the faster the movement the more likely they are to experience symptoms. Another common symptom is an over dependence on visual and tactile information for balance. This can present as increased dizziness and imbalance in the dark or in busy visual environments, or when walking on uneven or unpredictable surfaces.

Vestibular evaluation can determine the location and extent of the injury, and track recovery of visual stability and overall balance. Most tests involve tracking the eye’s response to various stimulation of the inner ear. This stimulation can include slow movement, fast movement, vibration, sound, position change, or temperature change. Not all clinics offer all these tests.

Overall balance can be assessed informally by trained physical therapists, or through the use of a computerized platform that simulates a variety of environmental conditions.

Treatment –Chronic Phase

Medications such as meclizine should be avoided as they can inhibit recovery. Therapy involving visual stability exercises and balance exercises that gradually reduce visual and tactile feedback have been shown to minimize the impact of any permanent inner ear weakness. Some patients can complete these exercises at home, while others are better managed under the supervision of a Physical Therapist.

Despite optimal treatment, some patients have lasting symptoms. These can include brief dizziness or visual disorientation with quick head movements, or transient surfacing of balance complaints, more notable when the patient is fatigued, stressed or battling some other illness.

About the author

Alan Desmond, AuD, is the director of the Balance Disorders Program at Wake Forest Baptist Health Center, and holds an adjunct assistant professor faculty position at the Wake Forest School of Medicine. He has written several books and book chapters on balance disorders and vestibular function. He is the co-author of the Clinical Practice Guideline for Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV). In 2015, he was the recipient of the President’s Award from the American Academy of Audiology.

Alan Desmond, AuD, is the director of the Balance Disorders Program at Wake Forest Baptist Health Center, and holds an adjunct assistant professor faculty position at the Wake Forest School of Medicine. He has written several books and book chapters on balance disorders and vestibular function. He is the co-author of the Clinical Practice Guideline for Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV). In 2015, he was the recipient of the President’s Award from the American Academy of Audiology.