If you listed the most common problems that your hearing aid patients complain of when they return to your office, number one on the list would be, “I can hear, but I can’t understand the words.” Or, to put it differently, “The hearing aids are giving me more sound, but this sound does not help me distinguish the words people are saying to me.”

Resolving this problem may require a significant amount of work from the professional. The solution may be high tech or low tech. Most of the time, substantial improvement is possible. However, the condition of “I’m not understanding” is often complicated by wax or dead skin in the ear canal; dirty, distorted, and weak hearing aids; patients who are unable or unwilling to push buttons and/or make adjustments; and family members who are not helpful.

Over time, all hearing aids get “dirty and weak,” and the brightness and clarity of the amplified sound decreases. New microphones and receivers will often markedly improve the quality of the sound. Unfortunately, some unscrupulous hearing aid practitioners may take advantage of this situation to attempt to sell people new hearing aids every time they come to the office with a complaint about the sound. In fact, though, with proper maintenance, a good set of hearing aids should last several years. This maintenance includes seeing one’s hearing aid professional on a regular basis, say every six months.

Many hearing aids come without a volume control and are programmed to adjust the level of amplification automatically. In such cases, if a patient needs more amplification to hear better, he will have to return to the office to have the instruments re-programmed.

In handing this situation, good communication among the practitioner, the patient, and the patient’s family is essential. Family members can talk to and work with the patient. Sometimes when more sound is needed, a family member can even bring the hearing aids into the office to have them adjusted without the patient being present. We only do this, however, when it is difficult for the patient to come.

Ability to Hear in Quiet Environment

When a patient tells me, “I hear, but I don’t understand,” I always ask “Hear where?” Helping patients hear in the quiet of their home is a completely different task from helping them hear well in a noisy restaurant.

Helping patients hear better in quiet is usually a matter of increasing the bandwidth (adding more gain in the very low-frequency and very high-frequency ranges), eliminating all types of distortion (e.g., irregular, peaky frequency response curves), and giving them enough sound. I will discuss these topics in the future. I conduct word-understanding tests at varying intensity levels (as discussed in my previous post) to figure out how to help the patient.

Hearing Aid Performance in Noise

Helping a patient hear well in a high-level noise environment requires a very different solution. Using too much gain in the lower frequencies can quickly destroy the effectiveness of a “noisy listening” program. When I am working on a program for listening in noise, I first make sure the patient has the potential to hear well in noise with properly fitted hearing aids. There are a couple of quick and easy ways to determine if this is the case, which I will discuss in future blog posts.

Once I have determined that the patient’s ears will be able to hear well in noise, I focus my attention on how much speech information the patient is getting when wearing the hearing aids in a noisy environment. Later on, I will explain how to “load” a hearing aid to do these tests. For now, let me simply say: Use high-level inputs (e.g., an 80-dB composite noise) and look at the REAR (real-ear aided response).

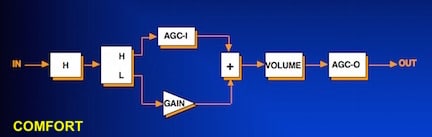

When you put a loud input signal into a hearing aid, you activate the AGC (automatic gain control) circuits. That means that if you use too much AGC, i.e., you have set the compression to an aggressive level, the hearing aid effectively turns off. Since most people are able to improve their hearing in noise if they put their hand behind their ear, I use the hand-behind-the-ear response as a minimum target for my “hearing well in background noise listening program.”

To summarize all this simply, make sure the patient can hear well under some conditions, then try to replicate these conditions with a pair of well-fitted hearing aids. It takes work–sometime a lot of work–and it takes time. But it is the greatest feeling in the world to know that my patient can hear because I did my job right.

Doesn’t word recognition have a lot to do with hearing the words but not understanding them? If you have a low word recognition score, isn’t true that even with hearing aids, you won’t understand some words? Even with new miss and receivers?

I totally disagree with Jeff’. I am extremely confident in my word recognition and have taken tests to prove it. I can hear; but, I have a problem understanding them. The words sound garbled “with some” individuals; but not all. If I remove my hearing aids ; and as stated above; If I put my hands behind my ears , the words that were garbled by a speaker before are now clear. This would indicate to me that it has nothing to do with word recognition score. With the hearing aids , Jeff sounds like Jrrrrefff. With my hands behind my ears ; the word Jeff sounds like Jeph (JEFF)