Harvey Abrams, PhD

By Harvey Abrams, PhD

In Kim Cavitt’s recent post, she argues that the disruptive forces facing our industry and profession can have the potential to positively impact accessibility to and affordability of hearing healthcare. I hope she’s right.

When most of us think about disruptive forces these days, our minds understandably turn to products, specifically PSAPs and other hearables and how they’re delivered (i.e., direct to consumer).

Indeed, the focus of the PCAST report is almost entirely devoted to improving accessibility and affordability through changes to the product (their cost and method of delivery). I would argue that the PCAST recommendations are very narrowly focused on the device part of the equation and that, while PSAPs and direct-to-consumer sales may decrease overall costs, they almost certainly won’t ensure the quality of care that our patients deserve and, in fact, may very well compromise that given the complete lack of attention given to the critical importance that professional services play in the management of individuals with hearing loss.

Separating Services from Device

Utilizing best practices in audiologic care can take time

There is another way to think about disruptive forces separate from the device – the way we as clinicians deliver our hearing care.

Consider the typical clinical encounter in many audiology practices: A patient checks in with the receptionist and waits until called. They’re brought back by the audiologist who conducts every aspect of the patient care encounter – the history, otoscopy, testing (manual audiometry, immittance, speech testing), review of the results, treatment planning, earmold impressions, ordering devices, report writing, etc. Depending on the complexity and comprehensiveness of the encounter, the audiologist can spend 60-120 minutes with the patient during this initial consultation.

Assuming amplification is recommended, the patient will return for the hearing aid fitting and once again, the audiologist conducts each aspect of this encounter – unpacking the instruments from the box, running an ANSI specification check, connecting the hearing aids to the software, programming and verifying the instrument parameters on the patient, instructing the patient on the use and care of the devices, counseling the patient on expectations, warranty information, batteries, etc. Again, another 60-90 minutes.

The patient will return for follow up and, once again, it’s the audiologist who checks the ears, the hearing aids, the progress, makes adjustments, – another 30-60 minutes. Depending upon the follow-up schedule, this process is repeated several more times throughout the year.

The most highly skilled and paid member of the clinic team is spending some 4-6 hours (more in the event of unscheduled visits) with a single patient throughout the year.

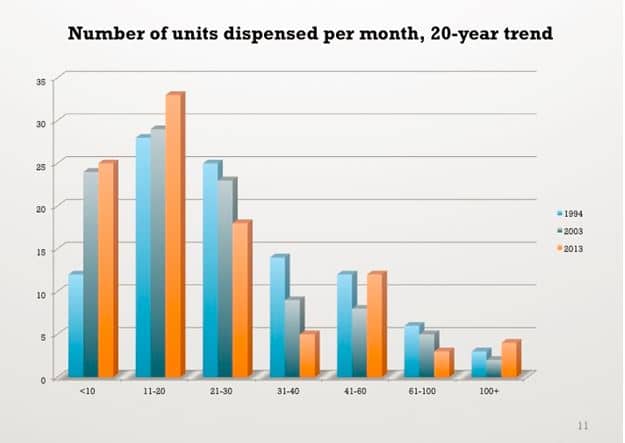

It’s no wonder that the cost of our bundled service is so high. It’s also no wonder that most practices sell no more than 20 units per month — the audiologist is spending a great deal of time with relatively few patients.

Adapted from: Strom KE. HR 2013 dispenser survey: Dispensing in the age of internet and big box retailers. Hearing Review. 2014;21(4):22-28.

Every system is perfectly designed for the results it gets and up until now, there has been no reason (financially) to change the prevailing system of hearing aid sales and delivery.

**Stay tuned next week for Part 2 of Dr. Abrams take on disruptive forces facing the hearing aid industry

.

Harvey Abrams, PhD, is a regular contributor to HHTM and works as an audiology consultant in the hearing aid industry. Dr. Abrams has served in various clinical, research, and administrative capacities in the industry, the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense. Dr. Abrams received his master’s and doctoral degrees from the University of Florida. His research has focused on treatment efficacy and improved quality of life associated with audiologic intervention. He has authored and co-authored several recent papers and book chapters and frequently lectures on post-fitting audiologic rehabilitation, outcome measures, health-related quality of life, and evidence-based audiologic practice. Dr. Abrams can be reached at hbabrams@gmail.com

There’s also the “dresser drawer effect.” If people start with hearables, and they don’t perform that well, they might end up in the dresser drawer, with the user less likely to pursue real hearing aids.