Editor’s Note: Today’s post continues the discussion by Abigail Farmer and Bruno Sarda on the evolution of hearing aid technology.

Alternatives to Hearing

As discussed previously, humans have always applied their creativity in pursuit of making things better. In the case of helping people hear better, we will first review technologies that have provided alternative to hearing, and we will then review technologies that actually assist in hearing better.

For as long as there have been people with hearing deficiencies, there have been attempts to help them overcome this handicap. Using gestures and hand signs is the oldest form of alternative to hearing. Some of these signs were developed into alphabets and languages, like the American Sign Language (ASL)1, itself believed to stem from an older sign language system established in France in the 1700’s.2 This can be extremely effective done face-to-face—any hearing person who’s traveled to a country where they don’t speak the language can attest to the effectiveness of gestures.

However, in the era of broadcast and distance communication, including radio, television and telephone, hearing impaired individuals are definitely disadvantaged. For example, written communication has long been an effective solution for hearing impaired individuals—they could always write what they wanted to communicate, and read messages of what others were saying.

However, in the era of broadcast and distance communication, including radio, television and telephone, hearing impaired individuals are definitely disadvantaged. For example, written communication has long been an effective solution for hearing impaired individuals—they could always write what they wanted to communicate, and read messages of what others were saying.

Adopting the telephone as a ubiquitous form of communication, including in the workplace, was a significant obstacle for the hearing impaired. It took decades to start overcoming this obstacle with technologies like TTY (Text Telephone), sometimes known as TDD (Telecommunication Device for the Deaf).

Television has a similar story. It also took decades before technologies like closed captioning (CC) were possible or even mandated, so prior to that, a very few broadcasts (primarily government-run) would have interpreters providing real-time translation into sign language in a small window on the screen. Interestingly, in recent times, text-based communication has seen a resurgence; technologies like email, texting or instant messaging have become ubiquitous at home and at work. This makes it easier for hearing impaired individuals to communicate.

Role of Policy in Shaping Hearing Aids as We Know Them

Although global approaches to hearing loss varies widely, this paper focuses primarily on American policies regarding hearing aids. Hearing aids’ technological development was not inevitable; rather, a series of political and social decisions made this happen.

Funding: Miniaturization, Transistors

Hearing aids consist of several component technologies, from transistors to batteries. The United States military was a critical source of funding that allowed these technologies to develop. The technology enabling smaller hearing aids was a result of the “philosophy of miniaturization” that the U.S. Army developed during World War II.3

Although hearing aid users had the strongest consumer demand for miniaturization, the military was no less anxious for miniaturization.4 Indeed, in 1946, the Army Signal Corps Engineering Laboratory(SCEL) Committee on Miniaturization declared that “miniaturization should and will be a major objective in the design of future Signal Corps’ equipment.”5

In particular, the SCEL focused its efforts on miniaturizing circuit-assembly techniques.6 Military investments during World War II gave post-war industry a starting point for button batteries and printed circuits, which were soon adopted by the hearing aid industry.7

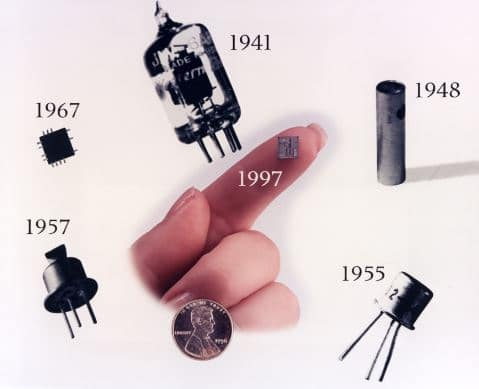

How the size of transistors evolved over time. Image courtesy gregd3

Miniature or not, transistor technology also relied heavily on military funding. Although much of the work on transistors took place in the Bell Telephone Laboratories, the Army Signal Corps’ investment heavily impacted both the content and style of transistor technology.8 During the war, military investment funded research on a variety of semiconductors: silicon at MIT and germanium at Purdue.9 After the war, the Office of Naval Research became the primary funder of research, but Bell Laboratories, as a company with independent means was able to continue its work, capitalizing on MIT and Purdue’s research while those institutions had to wait for further funding.10

Standardization of Batteries

Standardization’s importance to industry in general can hardly be overstated: it’s why we know that an electric device’s plug will fit in a wall socket or that a light bulb purchased at one store will fit a lamp purchased at another. Up until World War II, however, hearing aid users had to purchase batteries that were unique to their specific hearing aid.11 The War Production Board’s decision to standardize battery sizes freed hearing aid users from the constraint of a specific brand’s battery and allowed them to use universal sizes.12

Patents

Intellectual property rights are the quintessential incentive to encourage innovation, and they certainly played their part in incentivizing the development of hearing aid technology. One interesting exception is how Bell Laboratories’ handled its original patent on the transistor.

At the time the transistor was invented, AT&T was under investigation by the Justice Department to determine whether it had a “monopoly on telephone network gear through Western Electric.”13 Thus, in 1952, in an attempt to deflect criticism, AT&T offered to license its transistor patents for $25,000—or for free, if the company would use the transistor in hearing aids.14

Raytheon and other companies took advantage of the royalty-free license, putting transistors to use in hearing aids almost immediately.15

Hearing Loss Policy

Today American policy addresses hearing loss in four main ways: through policies directly addressing disabilities, policies addressing education of individuals with partial or total hearing loss, policies regarding hearing aid access, and military funding of research into hearing loss and treatments.

Current Policies Pertaining Specifically to Hearing Loss

Several state and Federal laws address the impact hearing loss has on Americans. For example,The Telecommunications Act of 1996 requires manufacturers of telecom equipment and providers of telecom services to ensure that their products are both accessible to and usable by individuals with disabilities.16 The purpose of this act was to ensure that individuals with disabilities have a broad range of telecommunication products and services available.

Individuals who suffer hearing loss in the course of their employment may obtain compensation for that loss. Although the concept of compensating workers for the loss of a body part has existed since the time of Hammurabi,17 modern workers’ compensation laws have their roots in the immediate aftermath of the Industrial Revolution, although it took a wave of social activism for workers’ compensation to gain traction in the United States.18

New technologies have created the need to compensate workers for hearing loss simply because prior to the Industrial Revolution, most occupations did not pose a long-term risk to workers’ hearing.

With the advent of factories and the widespread use of machine guns and other loud instruments of war, individuals found their hearing increasingly at risk; workers in cotton mills, for example, frequently suffered hearing loss.19 State and local governments thus needed a way to compensate workers.

Today, many states in the United States require that businesses have workers’ compensation coverage for work-related injuries, including hearing loss.20 If a worker’s hearing is impaired as a result of industrial work, then the employer must pay for audiology services, including providing a hearing aid, if a hearing aid would improve the worker’s ability to communicate.21 OSHA also sets standards for maximum exposure to loud noises.22

*Stay tuned for Part 9: ADA and Education of Deaf and Hard of Hearing people. Images courtesy IEEE, nj.com

References

- Baker-Shenk, C.L., Charlotte Baker, and Carol Padden. American Sign Language: A Look at Its History, Structure & Community. TJ Pub Incorporated, 1979.

- Marschark, Marc, and Spencer, Patricia Elizabeth. Oxford Handbook of Deaf Studies, Language and Education. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Mills, supra note 16, at 24.

- Id. at 25.

- William R. Stevenson, History Office: US Army Electronics Command, Miniaturization and Microminiaturization of Army Communications—Electronics, 1946–1964 (1966)

- Misa, supra note 51, at 263.

- Mills, supra note 16, at 25.

- Misa, supra note 51, at 255.

- Id. at 256–57.

- Id. at 558.

- Staab, Hearing Aid Evolution II, supra note 63.

- Id.

- Jeffery S. Young, Forbes Greatest Technology Stories: Inspiring Tales of the Entrepreneurs and Inventors Who Revolutionized Modern Business 72 (1998).

- Id.

- Id. at 73–74.

- 47 U.S.C. § 255.

- Gregory P. Guyton, A Brief History of Workers’ Compensation, 19 Iowa Orthopaedic J. 106, 106 (1999).

- Id. at 107–08.

- Jamie H. Evens, The Din of Machiens: The Technology of Textile Production, Windham Textile & Hist. Museum (last visited Apr. 25, 2016).

- 3 Modern Workers Compensation § 307:15 (2016); Workers’ Compensation Laws by State, Insureon,https://www.insureon.com/products/workers-compensation/state-laws/ (last visited Apr. 25, 2016).

- 2 Modern Workers Compensation § 202:14 (Mar. 2016)

- See, e.g., 29 C.F.R. § 1910.95 (West 2009).

Abigail Farmer graduated summa cum laude with B.A.s in French and Spanish from Texas A&M University. Before starting law school, she interned with the U.S. Commercial Service in Paris, France. Abigail served as Executive Note and Comment Editor for the Arizona State Law Journal from 2014–2015 and as the Hong Kong team editor for the Wilhem C. Vis International Commercial Arbitration Moot from 2015–2016. She also co-authored an article on bitcoins and estate planning, which won the Mary Moers Wenig Student Writing Competition and was published in the ACTEC Law Journal; she and her co-author presented the article at the Arizona State Bar Convention. Abigail is graduating summa cum laude with a J.D. from the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law and with an M.B.A. from the W.P. Carey School of Business. After graduation, Abigail will join Shell’s legal department in Houston, Texas

Bruno Sarda is a leading practitioner in the field of corporate sustainability at Dell, where he’s worked since 2005. In his role as Director of Social Responsibility, he leads the company’s strategy on social aspects of sustainability, including human rights and labor practices, working with internal and external stakeholders. He also manages Dell’s groundbreaking partnership with Phoenix-based TGen (Translational Genomics Research Institute) to accelerate adoption of precision medicine in addressing childhood cancer. In addition, Sarda is an adjunct faculty member and Senior Sustainability Scholar at Arizona State University, where he teaches and helped design and launch the Executive Master’s for Sustainability Leadership working with the Rob and Melani Walton Sustainability Solutions Initiatives at ASU.

Bruno Sarda is a leading practitioner in the field of corporate sustainability at Dell, where he’s worked since 2005. In his role as Director of Social Responsibility, he leads the company’s strategy on social aspects of sustainability, including human rights and labor practices, working with internal and external stakeholders. He also manages Dell’s groundbreaking partnership with Phoenix-based TGen (Translational Genomics Research Institute) to accelerate adoption of precision medicine in addressing childhood cancer. In addition, Sarda is an adjunct faculty member and Senior Sustainability Scholar at Arizona State University, where he teaches and helped design and launch the Executive Master’s for Sustainability Leadership working with the Rob and Melani Walton Sustainability Solutions Initiatives at ASU.