Editor’s Note: Today’s post continues a discussion on the evolution of hearing aid technology by Abigail Farmer and Bruno Sarda.

Going Beyond Human Abilities

The second thread in the pursuit of human enhancement does not focus on meeting existing societal expectations of what “normal” function is, but rather on exceeding the norm, and ultimately to change it by extending capabilities and creating a new baseline of function and performance.

Even humans with no difficulty walking have long desired increased mobility in order to reach destinations in less time as well as destinations farther away or not accessible on foot. As such, we learned how to ride animals, especially horses. We developed technology such as stirrups to make horses not only a quasi-extension of their own speed and strength, but to augment their strength to give them advantage in battle.1 We learned how to build rafts and canoes to ‘walk’ on water, and later ocean faring ships to explore distant continents. They developed bicycles, automobiles, railroads, airplanes and even space ships to satisfy our need for increased mobility, speed and distance.

If someone had told our grandparents at the turn of the 20th century that within their lifetimes we would succeed at safely transporting millions of human beings every day in machines flying tens of thousands of feet up in the air at speeds in excess of five hundred miles per hour, they could not have believed it.2

In the course of daily life, we quickly learned that physical limitations stood in the way of ambitions, so we devised tools that could cut, pierce, and break things that our hands could not. We devised weapons that enhanced our capabilities and enabled us to hunt and kill animals that were stronger or faster than we were. We trained and bred beasts of burden to do work we could not or didn’t want to do, and ultimately made machines that could multiply our strength and extend our capabilities to whole new levels.

Humans have also long sought to enhance their own physical performance and capabilities. Beyond eyeglasses, we also devised binoculars and telescopes to see farther than our eyes could see. We discovered that certain drugs did not merely restore lacking functions, but could enhance healthy functions as well; individuals without attention deficit disorder can use Adderall to take their concentration from standard to superhuman.

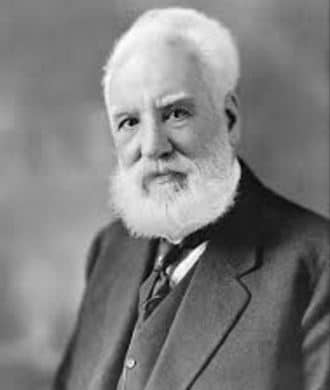

Rather than his many inventions, such as the telephone, Bell believed his greatest achievement was teaching deaf children

The telephone is another enhancement technology, giving us the ability to hear and speak to people who are too far out of range for our limited human hearing. Moreover, it is a key technology that ushered in the modern hearing aid. As we will develop further in this document, key scientific and technology development do not just happen. They are the result of a series of prior steps that tend to happen in nonlinear fashion, contrary to what Polanyi3 claimed and to some extent what Vannevar Bush wrote in his famous 1945 report.4 The reality, including for the development of the modern hearing aid, is much closer to the model Thomas Kuhn articulated.5 For example, it is notable that Alexander Graham Bell’s mother was deaf, and that Bell felt his greatest life achievement was not inventing the telephone, but rather his work teaching deaf children, as his father had done. It may therefore not be a coincidence that the first powered hearing aid was developed a mere twenty years after the invention of the telephone, by another inventor motivated to solve the plight of a hearing impaired loved one.

Technology to Enhance Hearing

Defining “Hearing Aid”

This paper considers the technology known as ‘hearing aids’. Certainly the most common perception of what this term entails is the assistive medical device that “old people” wear in their ears. But that is an oversimplification. What constitutes a hearing aid? The ability to receive sound and amplify it for its user? Modern telephones fit that description, as do headsets and headphones. This is no coincidence, as the technologies are closely related, born from the same inventions. Hearing aids are complex devices, born of centuries of technological advancement, user-driven modifications, and both market and political forces. For purposes of this paper, however, hearing aids are devices that enhance the hearing capacity of their user, with a primary, but not exclusive, focus on people seeking to regain hearing function lost as a result of age, disease or injury, as opposed to people born with severe or complete hearing loss.

History of Hearing Aid Technology

Hearing aids existed long before they could be worn. Humans have used various methods to improve hearing for a very long time6, but engineered devices started appearing in the 1600s. These were mechanical devices, the most recognizable of which are ear trumpets. These funnel-shaped devices helped capture, amplify, and guide sound waves into the ear canal. They were usually made of sheet metal, but some were made from wood, silver, and less commonly from materials such as snail shells and animal horns.7 Other devices like speaking tubes, following a similar amplification concept, could be built in to furniture, including a famous acoustic throne built for the king of Portugal in the early 1800’s.

*Stay tuned for part 3: the first electric hearing aids

References:

- See generally Lynn T. White, Stirrup, Mounted Shock Combat, Feudalism, and Chivalry, in Medieval Technology and Social Change 1–38 (1962).

- Michael Polanyi, The Republic of Science: Its Political and Economic Theory, 1 Minerva 54–73 (1962).

- Vannevar Bush, Office of Scientific Research and Development, Science, The Endless Frontier (1945).

- Thomas Kuhn, Anomaly and the Emergence of Scientific Discoveries and Crisis and the Emergence of Scientific Theories, in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions 52–76 (1962).

- Daniel Sarewitz, Address at the Workshop on Transhumanism and the Meaning of Progress: Technology in the Culture of Progressat Arizona State University (2008).

- Simply cupping one’s hand around one’s ear is probably the simplest way to correct (or augment) minor hearing loss.

- Hearing Aids: The Past, the Present, and the Future,Worth Hearing Center (Dec. 1, 2015), https://www.worthhearing.com/hearing-aids-the-past-the-present-and-the-future/.

*title image courtesy e-gps

Abigail Farmer graduated summa cum laude with B.A.s in French and Spanish from Texas A&M University. Before starting law school, she interned with the U.S. Commercial Service in Paris, France. Abigail served as Executive Note and Comment Editor for the Arizona State Law Journal from 2014–2015 and as the Hong Kong team editor for the Wilhem C. Vis International Commercial Arbitration Moot from 2015–2016. She also co-authored an article on bitcoins and estate planning, which won the Mary Moers Wenig Student Writing Competition and was published in the ACTEC Law Journal; she and her co-author presented the article at the Arizona State Bar Convention. Abigail is graduating summa cum laude with a J.D. from the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law and with an M.B.A. from the W.P. Carey School of Business. After graduation, Abigail will join Shell’s legal department in Houston, Texas

Abigail Farmer graduated summa cum laude with B.A.s in French and Spanish from Texas A&M University. Before starting law school, she interned with the U.S. Commercial Service in Paris, France. Abigail served as Executive Note and Comment Editor for the Arizona State Law Journal from 2014–2015 and as the Hong Kong team editor for the Wilhem C. Vis International Commercial Arbitration Moot from 2015–2016. She also co-authored an article on bitcoins and estate planning, which won the Mary Moers Wenig Student Writing Competition and was published in the ACTEC Law Journal; she and her co-author presented the article at the Arizona State Bar Convention. Abigail is graduating summa cum laude with a J.D. from the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law and with an M.B.A. from the W.P. Carey School of Business. After graduation, Abigail will join Shell’s legal department in Houston, Texas

Bruno Sarda is a leading practitioner in the field of corporate sustainability at Dell, where he’s worked since 2005. In his role as Director of Social Responsibility, he leads the company’s strategy on social aspects of sustainability, including human rights and labor practices, working with internal and external stakeholders. He also manages Dell’s groundbreaking partnership with Phoenix-based TGen (Translational Genomics Research Institute) to accelerate adoption of precision medicine in addressing childhood cancer. In addition, Sarda is an adjunct faculty member and Senior Sustainability Scholar at Arizona State University, where he teaches and helped design and launch the Executive Master’s for Sustainability Leadership working with the Rob and Melani Walton Sustainability Solutions Initiatives at ASU.

Bruno Sarda is a leading practitioner in the field of corporate sustainability at Dell, where he’s worked since 2005. In his role as Director of Social Responsibility, he leads the company’s strategy on social aspects of sustainability, including human rights and labor practices, working with internal and external stakeholders. He also manages Dell’s groundbreaking partnership with Phoenix-based TGen (Translational Genomics Research Institute) to accelerate adoption of precision medicine in addressing childhood cancer. In addition, Sarda is an adjunct faculty member and Senior Sustainability Scholar at Arizona State University, where he teaches and helped design and launch the Executive Master’s for Sustainability Leadership working with the Rob and Melani Walton Sustainability Solutions Initiatives at ASU.