Editor’s Note: Today’s post continues the discussion by Abigail Farmer and Bruno Sarda on the evolution of hearing aid technology.

Changing Hearing Aid User Demographics

In 2013, there were 44.7 million individuals over the age of sixty-five in the United States, or about 14% of the population.1 This age group is expected to grow to 21.7% of the population by 2040, and by 2060, it is estimated that there will be 98 million individuals over the age of sixty-five—twice as many as in 2013.2 If nearly half of the population over age of seventy-five suffers from hearing loss, the number of individuals requiring hearing aids will increase by tens of millions over the next few decades.

Another growing population who will require hearing aids is veterans. Because soldiers are at high risk of exposure to loud noises or explosions and head trauma, they are particularly vulnerable to noise-induced and trauma-induced hearing loss.

Indeed, more than 350 thousand service members suffer from tinnitus, while more than 250 thousand have hearing loss.3 In 2010 alone, more than 92 thousand unique claims of tinnitus were reported.4 The cost of these disabilities is at least one billion dollars for hearing loss and over $330 million for tinnitus.5

Deaf Culture

Although hearing loss definitely carries a stigma, Deaf Culture stands out as an exception to this rule. Whereas individuals with hearing loss express concern about being considered “disabled” or “old,” Deaf6 people take pride in their language and experience joy in their communities.7 They celebrate their struggle “to explain to themselves and each other their own existence in the world.”8

Image courtesy deafculturalcenter

This struggle is shared with a community bound by a shared human experience, not by a sense of isolation due to the inability to hear.9 After all, Deaf people do not see themselves as broken, needing to be fixed. They desire the same recognition as “language users, which means they want to be granted the same acceptance that would be given to any other language.”10

Consequently, devices like cochlear implants are viewed with hostility in Deaf communities. Despite impressively optimistic newspaper headlines,11 Deaf people view these implants as nothing more than experiments conducted on non-consenting children.12 Rather than a scientific advancement, these devices are yet another way that hearing society oppresses the Deaf.13

This is not to say that all individuals with total hearing loss identify as Deaf and reject all technology to restore (or even create) hearing abilities. Even so, because cochlear implants must be implanted at a very young age for the best spoken language acquisition outcomes,14 and because cochlear implants are essentially rejection of Deaf culture, the choice to have the procedure performed on an infant is troubling.

While Deaf Culture is a rich topic that is beyond the scope of this paper, this alternate perspective is important to note.

Causes of Hearing Impairment and Current Treatments

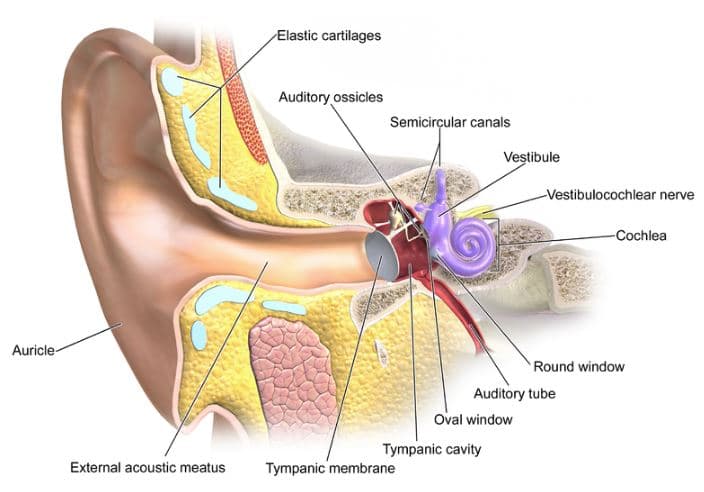

No discussion of hearing aids is complete without discussing the main causes of hearing loss. Hearing loss takes three forms: conductive, sensorineural, or mixed conductive and sensorineural hearing loss.

Each kind of hearing loss differs in causes, severity, and treatment; however, “half of all cases of hearing loss are avoidable through primary prevention.”16

Conductive hearing loss is hearing loss resulting from problems with the ear canal, eardrum, or middle ear.17 This can be caused by congenital conditions such as the ear canal’s failure to be open at birth (or total absence); absence, malformation, or dysfunction of middle ear structures, or the condition otosclerosis, which causes bones in the middle ear to not vibrate, leading to hearing loss by early adulthood.18 Diseases like chronic ear infections and tumors also cause conductive hearing loss.19 Finally, trauma like skull fractures can lead to hearing loss.20

Image courtesy Wikipedia

Sensorineural hearing loss, known as nerve-related hearing loss, results from problems with the inner ear.21 Causes include exposure to loud noises, head trauma or rapid decreases in air pressure (such as during a plane’s descent), viruses or other diseases, aging, genetic predisposition, and tumors.22 Like conductive hearing loss, treatment depends largely on the cause of hearing loss.23 Corticosteroids can reduce cochlear hair cell swelling, emergency surgeries can sometimes restore hearing loss due to head trauma, viral-caused hearing loss can be treated with drugs; and removing tumors can restore hearing loss when the tumors are small and the hearing loss is mild.24 Irreversible sensorineural hearing loss is the most common form of hearing loss; this is treated with hearing aids and, if hearing aids are ineffective, cochlear implants.25 Mixed hearing loss occurs when an individual has both conductive and sensorineural hearing loss;26 a combination of treatments is usually best.27

Treating hearing loss is extremely important, as untreated hearing loss can lead to a variety of problems, including serious emotional and social consequences, reduced job performance, and diminished quality of life.28 Basic cognitive abilities can be affected, because so much energy goes towards understanding speech.29

Untreated hearing loss can also lead to auditory deprivation: when the nerves responsible for hearing atrophy due to lack of stimulation.30 This can occur when hearing loss is untreated or if only one ear is fitted with a hearing aid—the unaided ear weakens over time and it becomes more difficult to understand spoken language.31

*Stay tuned for Part 8: Alternatives to Hearing; title image courtesy Siemens

References:

- Aging Statistics, U.S. Dep’t Health & Human Services: Administration for Community Living, https://www.aoa.acl.gov/aging_statistics/index.aspx (last visited Apr. 25, 2016).

- Id.

- Mission and Overview, Dep’t Defense Hearing Center of Excellence,https://hearing.health.mil/AboutUs/Mission.aspx (last visited Apr. 25, 2016).

- Id.

- Id.

- When spelled with a lowercase D, “deaf refers to those for whom deafness is primarily an audiological experience” and is usually applied to individuals “who lost some or all of their hearing in early or late life.” These individuals prefer to try and remain in the society in they were socialized. When spelled with an uppercase D, “Deaf refers to those born Deaf or deafened in early (sometimes late) childhood, for whom the sign languages, communities, and cultures of the Deaf collective represents their primary experience and allegiance.” Paddy Ladd, Understanding Deaf Culture: In Search of Deafhood xvii (2003).

- Id. at 3.

- Id.

- Id.

- Id. at 8.

- For example, “New Miracle Cure for Deaf Baby” or “Wonder Cochlear Implant Operation Abolishes Deafness.” Id. at 30.

- Id. at 30–31.

- Id. at 165

- See John K. Niparko et al., Spoken Language Development in Children Following Cochlear Implantation, 303 J. Am. Med. Ass’n 1498 (2010).

- Bob Traynor, Cultural Differences in Hearing Aid Use, Hearing Health & Tech. Matters (May 20, 2015), https://hearinghealthmatters.org/hearinginternational/2015/cultural-differences-in-hearing-aid-use/.

- Types, Causes and Treatment,Hearing Loss Association of America, https://www.hearingloss.org/content/types-causes-and-treatment (last visited Mar. 13, 2016).

- Id.

- Id.

- Id.

- Id.; H.P. Niedermeyer & W. Arnold, Otosclerosis and Measles Virus—Association or Causation?, 70 ORL 63, 63 (2008) (finding such high correlation between increased rates of measles vaccinations and decreased rates of otosclerosis that it is “most plausible that MV is at least one triggering factor for the development of otosclerosis”).

- Types, Causes and Treatments, supra note 11.

- Id.

- Id.

- Id.

- Id.

- Types, Causes and Treatments, supra note 111.

- Id.

- Hearing Aids Improve Brain Function in People with Hearing Loss, News Medical (Jan. 30, 2016, 2:35 AM), https://www.news-medical.net/news/20160130/Hearing-aids-improve-brain-function-in-people-with-hearing-loss.aspx.

- Id.

- Hearing Loss: Use It or Lose It, Healthy Hearing (Apr. 5, 2010), https://www.healthyhearing.com/content/articles/Hearing-loss/Causes/46306-Hearing-loss-auditory-deprivation.

- Id.

Abigail Farmer graduated summa cum laude with B.A.s in French and Spanish from Texas A&M University. Before starting law school, she interned with the U.S. Commercial Service in Paris, France. Abigail served as Executive Note and Comment Editor for the Arizona State Law Journal from 2014–2015 and as the Hong Kong team editor for the Wilhem C. Vis International Commercial Arbitration Moot from 2015–2016. She also co-authored an article on bitcoins and estate planning, which won the Mary Moers Wenig Student Writing Competition and was published in the ACTEC Law Journal; she and her co-author presented the article at the Arizona State Bar Convention. Abigail is graduating summa cum laude with a J.D. from the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law and with an M.B.A. from the W.P. Carey School of Business. After graduation, Abigail will join Shell’s legal department in Houston, Texas

Bruno Sarda is a leading practitioner in the field of corporate sustainability at Dell, where he’s worked since 2005. In his role as Director of Social Responsibility, he leads the company’s strategy on social aspects of sustainability, including human rights and labor practices, working with internal and external stakeholders. He also manages Dell’s groundbreaking partnership with Phoenix-based TGen (Translational Genomics Research Institute) to accelerate adoption of precision medicine in addressing childhood cancer. In addition, Sarda is an adjunct faculty member and Senior Sustainability Scholar at Arizona State University, where he teaches and helped design and launch the Executive Master’s for Sustainability Leadership working with the Rob and Melani Walton Sustainability Solutions Initiatives at ASU.

Bruno Sarda is a leading practitioner in the field of corporate sustainability at Dell, where he’s worked since 2005. In his role as Director of Social Responsibility, he leads the company’s strategy on social aspects of sustainability, including human rights and labor practices, working with internal and external stakeholders. He also manages Dell’s groundbreaking partnership with Phoenix-based TGen (Translational Genomics Research Institute) to accelerate adoption of precision medicine in addressing childhood cancer. In addition, Sarda is an adjunct faculty member and Senior Sustainability Scholar at Arizona State University, where he teaches and helped design and launch the Executive Master’s for Sustainability Leadership working with the Rob and Melani Walton Sustainability Solutions Initiatives at ASU.