Try this experiment. Poke or drill a hole lengthwise in one of those yellow foam earplugs that are worn for hearing protection. They can be obtained from your local audiologist or even a pharmacy. For those technical people out there, the hole should be about 2.5 mm in diameter. Then place a standard #13 piece of hearing aid tubing through the hole that you have just drilled. It should fit snugly because the outside diameter of #13 tubing is also about 2.5 mm. (The inside diameter is 1.96 mm, but that’s exciting and interesting for party conversations, but irrelevant for this experiment). This is an earplug that typically comes with many off-the-shelf insert earphones. Now compress or squish up the foam plug by gently rolling it between your fingers- the normal instructions for placing it into your ear.

But wait! Something has gone wrong. The #13 piece of hearing aid tubing that was placed snugly into the hole drilled through the foam plug has just fallen out. Well, let me try again… the same thing happens.

It turns out that when you are about to insert a foam earplug into your ear and you begin by compressing or squishing it, the inner diameter of the foam earplug (the hole) becomes larger. This is really counter-intuitive, and although I have seen it demonstrated many times, have done this experiment myself many times, and even have had the physics of this explained to me (many times), I still find it counter-intuitive and almost magic.

The solution is, of course, just to glue the tubing into the foam insert ear plug. If you buy any insert earphones on the market, they usually come with an assortment of ear tips, some of which are foam earplugs with a silicon “sleeve” or tubing that is inserted down the center for the sound to go through. And all of these sleeves are well-glued onto the foam earplug.

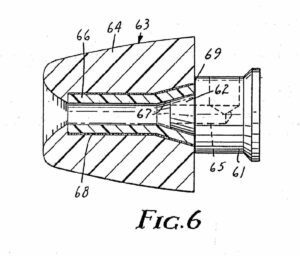

This is an important fact of life- it’s almost a given that you need to glue the tubing into the foam or else it will slip out. Here is one of the many figures from the 1986 Oliveira patent showing the need for a (permanently glued) piece of tubing (tubing marked in the figure as “66” and the glue is marked as “68”).

But, this was not always understood and it took someone like Dr. Bob Oliveira back in the mid-1980s to understand this and even patent it. In 1986, Bob received two patents on this (and patents are good for 20 years by the way). To get a patent, among other things, you must demonstrate that you have invented something new or added something to the state of the art that was not previously known or understood. The US Patent Office agreed that “simply” gluing the tubing into a foam earplug would make the difference between a successful product and one that would keep falling out of the ear. At the time, others had noticed this, but it was not well known or understood.

It may seem like a small thing, but Bob’s company Hearing Components, Inc. (www.complyfoam.com), which markets products such as the Comply brand of sticky tape for poorly fitting hearing aids and products for controlling earwax, defended its 1986 patents when it brought a successful patent-infringement suit against a company that used his patented approach while the patent was still in effect). I was one of the expert witnesses at the time, but that’s a whole different story.

Even though we now take for granted insert earphones coupled to foam earplugs (that do not fall out of the ear), the innovation that allowed it to be a reality came from the mind of Bob Oliveira.

In part 2 of this series, we will learn why patients should keep their mouths open during earmold impressions, especially if we want to give them a good seal and an associated good bass response. That is a Bob Oliveira idea as well.