Once upon a time (actually a month ago), I had a client who wanted to get custom silicon earplugs for his in-ear monitors. Of the many “connectors” for in-ear monitors, the most common is a stem that is on the order of 2.5 mm in diameter and extends about 8-10 mm in length. There is no magic in these numbers, but they are fairly common in the industry. In most cases, I send the actual ear monitor to the earmold laboratory to avoid “surprises.” Yet sometimes surprises occur.

The decision that earmold laboratories need to make–and this is where the surprises sometimes occur–is whether to simply drill a 3.1-mm inner diameter hole through the earmold (in the same way that they would drill a 3.1-mm diameter hole for any behind-the-ear hearing aid earmold that uses standard #13 tubing) OR, to drill a narrower hole (about 2.5 mm in inner diameter). In other words, should the laboratory install a piece of #13 tubing that runs through the custom silicon earmold and have the in-ear monitor sit inside the #13 tubing cuff OR just have the in-ear monitor sit “naked” inside the earmold and be held in place by the friction of the in-ear monitor against the silicon wall?

Well, before I get back to the client whom I saw a month ago, you are all probably screaming at the computer screen that the outer diameter of #13 tubing is less than 3 mm so why use a 3.1-mm bore to drill the hole? If silicon is used, when one drills a hole using a 3.1 mm drill bit, it actually snaps back to an inner diameter of between 2.5 and 2.8 mm. The same cannot be said of a hard material such as Lucite, but silicon seems to be the earmold of choice for those using in-ear monitors. This is just trivia, however, and should be reserved for cocktail party conversation.

The following picture shows my in-ear monitors inserted into a custom silicon earmold without #13 hearing aid tubing. It seems to work well and I have been using it for a number of years in this fashion.

But, now back to my client. I had recently made custom silicon earmolds for his new monitors and he thought that they sounded great. Well, last week he was back in my office with a complaint that he sweats a lot when playing and the earmolds slip out of his ear. I offered to remake the molds with a longer bore that goes into the canal, but I thought that I would try one more thing before I did that- he had a gig that night and didn’t want to give up his earmolds.

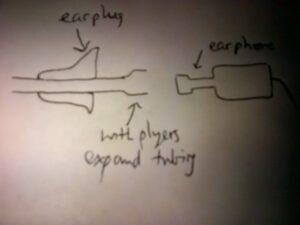

The following figure is what I drew on a napkin while having a beer with friends that evening.

A schematic drawn in a pub showing how #13 tubing can be installed in an in-ear monitor to improve retention and the bass response

It involves a top secret (CIA?) trick to allow the earmolds to fit better in his ear (less sweat-induced slippage), allow the in-ear monitor to stay firmly in the earmold, and allow a better bass response. To explain the picture, a small piece of #13 standard hearing aid tubing was placed through the earmold. A tubing expander (any needle-nose pair of plyers will do) expanded the outer side of the #13 tubing such that the bore of the in-ear monitor can be slid into the tubing. Once done, the #13 tubing was pulled through the custom earmold medially (toward the inside) such that the in-ear monitor sat firmly against the outer portion of the earmold.

This expanded the outer dimensions of the silicon earmold slightly to provide better retention in the ear for this sweaty musician, provided a firmer joining of the in-ear monitor and earmold, and sealed off any unintentional slit leaks on the outside of the earmold- most likely on the anterior side where jaw movement can be a culprit. This last part improved the bass response by plugging the acoustic leak.

An informal survey of about 10 earmold labs around North America indicated that seven of them use #13 tubing for situations like this, two don’t, and the last guy who answered the phone only wanted me to order a pizza. They had pretty good specials too.