I am always surprised by how the various hearing aid manufacturers lump the two words “speech” and “music” together in one sentence…. “Hearing aid X can help with speech and music, and can help you jump higher and run faster….”. Of course everyone knows that the last part is true and many of my hard of hearing clients can leap tall buildings in a single bounce. But lump “speech” and “music” together in one sentence??!!

In many ways, the construction of speech is much more-simple than that of music. I am fond of saying that speech is sequential and music is concurrent. Speech is one speech segment followed by another in time. There are some overlaps which speech scientists call “co-articulation” and some assimilation of one speech sound with an adjacent one and linguistics would refer to this as being governed by “phonological rules” but in the end, speech is characterized by either lower frequency vowels and nasals (sonorants) one moment and possibly higher frequency stops, fricatives, and affricates (obstruents) the next moment. Speech does not have both low frequency sounds and high frequency sounds at the same time. It is like playing the piano keyboard with only one hand – you are either playing on the left side, the middle, or the right side, but never both sides at the same time. Speech is sequential – one sound at a time followed by another sound, a moment later.

In many ways, the construction of speech is much more-simple than that of music. I am fond of saying that speech is sequential and music is concurrent. Speech is one speech segment followed by another in time. There are some overlaps which speech scientists call “co-articulation” and some assimilation of one speech sound with an adjacent one and linguistics would refer to this as being governed by “phonological rules” but in the end, speech is characterized by either lower frequency vowels and nasals (sonorants) one moment and possibly higher frequency stops, fricatives, and affricates (obstruents) the next moment. Speech does not have both low frequency sounds and high frequency sounds at the same time. It is like playing the piano keyboard with only one hand – you are either playing on the left side, the middle, or the right side, but never both sides at the same time. Speech is sequential – one sound at a time followed by another sound, a moment later.

Music is concurrent; unlike speech, we must have both low frequency sounds and high frequency sounds that occur at the very same time. Musicians call this harmony. Even while playing a single note on the piano keyboard, there is the fundamental or tonic – the note name that is played – and then integer spaced multiples of that note spread out on the right hand side of the piano.

Music cannot be like speech, one frequency region at a time. And speech cannot be like music, many frequency regions at a time.

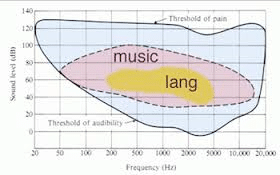

Graphs that compare music and speech are simplistic; they should not be used to define amplified frequency responses or the characteristics of compression circuitries. They look pretty but have very limited value.

Algorithms that have been optimized for hearing speech need to be different than those that are optimized for listening to music. Even something as simple as feedback management can be quite useful for speech but disastrous for music. Imagine a feedback management system that confuses a high frequency harmonic for feedback- music would essentially be shut off. Ad hoc features such “only restrict the feedback manager to sounds over 2000 Hz” would be slightly better than feedback managers that are active in all frequency regions, but even then, the higher frequency harmonics of the music would be nullified.

Another algorithm that has shown itself to be of great assistance with speech is frequency transposition or frequency compression. These phrases are meant to apply to the wide range of frequency shifting algorithms that are available including linear and non-linear shifting and compression. Imagine the second or third harmonic of a note being moved elsewhere. Discordance will result.

The best music algorithm for severely damaged cochlear regions would not be to transpose away from that region, but simply reduce the gain in that frequency region. A creation of additional in-harmonic energy where it is not supposed to be will ruin music.

And indeed, in most cases of algorithms for amplifying music, less is usually more. Turn off the fancy stuff and just listen to the music. Wider or narrower frequency responses have nothing to do with the input source- music or speech- and as such should not be different between a “speech in quiet” program and a “music” program.

Please authorize me to translate and publish this wonderful paper into my Chinese website.

Thanks.

Yes- glad to provide permission. Please quote the Hearing Health Matters site. Best regards, Marshall

Listening to recorded music, through a good system with excellent speakers, by way of top notch hearing aids is, for me, an ugly experience. However, that same recording, sent wirelessly by Blue-tooth directly to those same hearing aids is as close as I can remember to the real thing. Why is this?

This is an interesting comment- not sure why this is the case. Even Bluetooth will need to go through the same front end A/D conversion process as the normal microphone route. Anyone out there with an answer to this?

With thanks, Marshall

I have asked Steve Armstrong of Sounds Good Lab to respond to some of the comments from Peter Chellew. Steve is an engineer who has designed many circuits (both analog and digital) that have been used in the hearing aid industry since the mid 1980s. He actively consults to manufacturers within the hearing health care industry. These are questions that should be directed to your local audiologist and working together, an optimal set of software and hardware features can be obtained.

Marshall Chasin

****************

Actually the Bluetooth audio stream most likely remains in the digital domain, which would bypass any HA front end issues.

Peter, can you provide a little more insight on the conditions for the experiences you mention?

Is your fitting an “Open” one in which the sound arriving at your ear drum is the combination of sound from HA output as well as sound directly entering into your ear canal?

When trying to listen to the speakers does your perception of the sound quality improve if you lower the sound level in the room?

When you are listening to Bluetooth direct is the same sound also being reproduced over speakers?

Have you compared with all features off? I would suspect there’s no filtering, shaping or other ballyhoo going on when streaming is occuring. The front-end shouldn’t be or no longer is a limitation in most top notch aids nowadays.