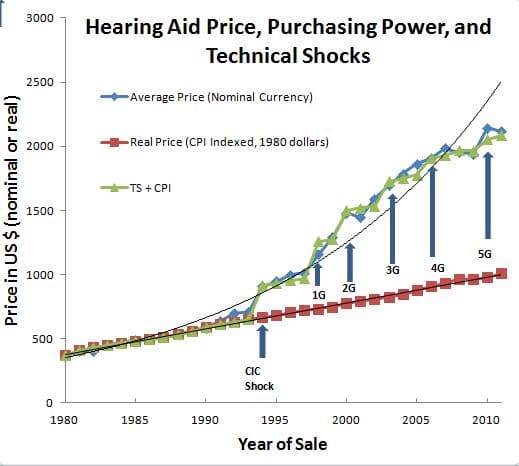

The average Price of hearing aids began rising faster than inflation in 1994 when the first truly differentiated product entered the market. In contrast, Price kept pace with inflation for traditional instruments, which tumbled into a new niche of “low end” products (see title figure). What does this mean?

More Economic Stuff (what you’ve been craving)

- Traditional hearing aids tracking inflation, as measured by the CPI’s representative “market basket of goods,” means that consumers’ Purchasing Power in real dollars for the commodity of hearing aids was stable over time.{{1}}[[1]]The basket of goods used for economic analyses such as CPI comprises a representative group of commodities, undifferentiated goods that change slowly or not at all (e.g., wheat/food) over time. The basket is periodically updated by adding or discarding items.[[1]]

- Price of all hearing aids, including newly introduced CICs and first generation digital instruments, rose faster than inflation after 1994. Another way to say that is that suppliers’ Pricing Power increased with technological innovations that enabled product differentiation. The flip side is that consumers’ Purchasing Power decreased for newly differentiated hearing aid products.

- Manufacturers vie for Market Power via technological innovation to create product differentiation.

- Market power makes a manufacturer a Price Maker instead of a lowly Price Taker. The firm with the most market power can command higher prices than competitors and take “abnormal” (positive) profits.{{2}}[[2]]Recall that maximum profit = 0 in perfect competition, because you sell right up until your marginal profit = marginal cost. When Profits > 0, there is imperfect competition, meaning you’ve got some kind of edge. Such profits are therefore “abnormal” in economics-speak.[[2]]

- Market power is a strong incentive for investment and innovation by manufacturers to maintain or obtain differentiated positioning.

- Market power increases with consolidation through mergers and acquisitions in product differentiated industries.

- Patents and patent protection provide, protect, and extend a firm’s market power.

The Changing Hearing Aid Marketplace

Since 1994, hearing aids qualify as a technology intensive industry, characterized by “continuous product innovation through successive generations of technologies within an existing technology standard, not unlike mobile phones. The result is a marketplace consisting of overlapping generations of products.”

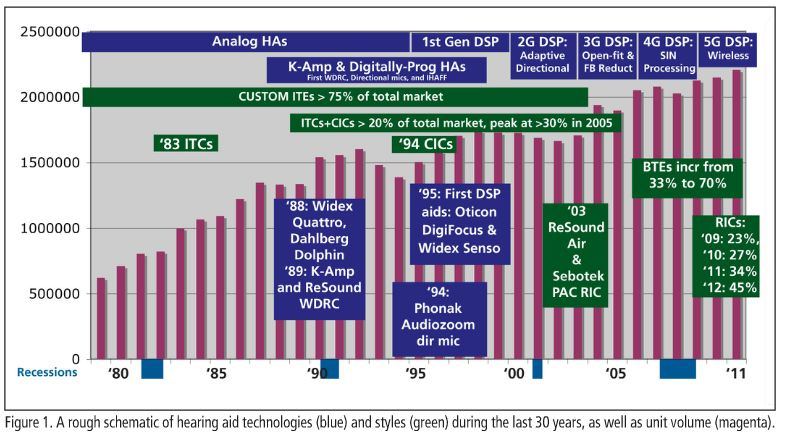

Figure 1 illustrates the point. It’s taken from Karl Strom’s editorial in this year’s January issue of Hearing Review.

Figure 1 illustrates the point. It’s taken from Karl Strom’s editorial in this year’s January issue of Hearing Review.

- Magenta vertical bars show us industry growth from the late 1970s through 2011 in terms of product sold in the US.

- Blue interrupted horizontal bars across the top mark milestones in technological innovation starting in the 1990s and continuing with successive generations.

- Blue and green boxes along the base and middle of the figure identify product differentiations by various manufacturers that were quickly picked up by rivals and came to dominate the industry until a new innovation stepped in. For example, custom canal instruments were a hallmark of the industry from 1994 through 2005. But RICs quickly prevailed, and continue to do so, after their introduction in 2003.

The Real Price of Hearing Aids in a Differentiated Product Market

Figure 2 is the grand finale of this Pricing series. It’s my attempt to talk meaningfully about Price in a technologically intensive industry by estimating and factoring in Pricing Power premiums that accrued with each major innovation shown in Figure 1 (1G = 1st generation DSP, 2G = 2nd general DSP, etc).

The rationale is my own and therefore open to critique and improvement: I take hearing aids in 1980 to represent the aforementioned “existing technology standard.” They were and remain plastic shells, worn at ear level, either in or on the ear, battery-powered, for the purpose of improving hearing in people with hearing loss. Industry technology “shocks” shown in Figure 1 represent the aforementioned “successive generations of technologies.”

The predicted Real Price of hearing aids in 1994 is $666 (1980$) but the actual average Price was $910, as shown respectively by the red box and blue diamond functions in Fig 2. The blue arrow signifies introduction of CICs that year as the first Technology Shock (TS) to the industry, instantly bifurcating the market into CIC and traditional instruments. Adding a TS price premium of $250 to the CPI prediction (green triangles) allows good tracking of actual average hearing aid prices for the next four years.

The next TS comes when Widex and Oticon introduce digital instruments to the US market in 1996/7. For the first time our industry becomes a “marketplace consisting of overlapping generations of products” and it takes a year or so for the Pricing effect of first-generation digital (G1 in Fig 1) to jump out on the graph. I estimate the Price Power premium of G1 at $275 starting in 1998. Adding that bump does a reasonable job of tracking actual average hearing aid price for the next few years, until G2 contributes another Price Premium several years later … and so on right up till 2011, though actual numbers get harder to come by as the years progress.

Pricing Premiums — Not Just Your Grandma’s Hearing Aid

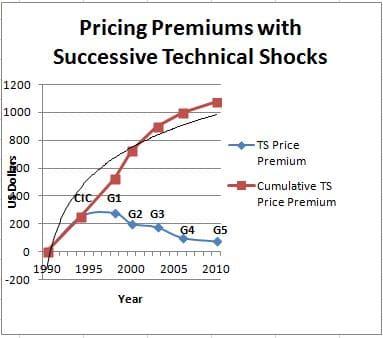

Figure 3 is my answer to the questionable quote that started this series: “The hearing aid industry uses every new thing, like digital or a new algorithm, to raise prices.”

The answer is a qualified Yes/No. Yes, major technological shocks come with price tags that manufacturers pass on to retailers and end users. Over 18 years, premium pricing has added just over $1000 to average Price, which translates to $59.70/year.

No, premium pricing does not happen with every new thing, but it does happen and it is the engine that drives rapid innovation in a technology intensive industry. Given the improvements for what it’s cost, I say full steam ahead.

And lest we forget the range of Price has grown with every differentiation. Low-end hearing aids going for $300 in today’s newspapers and on the Internet may be primitive but they feature CIC and digital processing technologies. Fig 2 tell us that even analog linear instruments — and I defy you to find one — should be clocking in at more than $1000 each in real dollars (1980$) on today’s market. Instead, first-generation technologies cost $40 less than traditional aids did in 1980. I say product differentiation has driven Price down for pioneer products.

Most importantly, note the logarithmic trend of cumulative price increases (red box function), based on a premium pricing surge function (blue diamonds), which peaked with the advent of CIC and first-generation digital technology and has been declining ever since, notwithstanding the revolutionary change wrought by RIC technology. Premiums are decreasing as technology is increasing. I say technology still costs money, but it’s getting cheaper.

There are a number of explanations to consider with Fig 3. Flattening prices may reflect more consumption of older, less expensive instruments as technological advances have become heavily overlapped in the industry. That raises another explanation, that flattening prices may reflect increasing Price Elasticity of Demand in a previously inelastic market as expanding product differentiation allows consumers more options and price points. Those of you who have mentioned falling prices in consumer electronics as a contrast to price growth in the hearing aid industry can take comfort that we will become more like other consumer industries as our market becomes more Price elastic.

If you are like me, this series raises more questions and objections than it answers. First question should be “How did you arrive at your numbers?” The quick answer is “Not easily and probably not entirely correctly.” I’m anxious to get smarter people with better numbers, or at least number sense, involved in this discussion. Toward that end, I will put the numbers out there in two weeks, after the bi-monthly patent review post.

In my dreams, I see someone taking the numbers, improving them, and sending me new, improved graphs. In my best dream, that someone is a tall dark and handsome economist who delivers beautiful graphs in person. Hello? Are you out there?

(editor’s note: this is Part 3 in the multi-year Hearing Aid Pricing series. Click here for Part 2 or Part 4)

WOULD YOU CONSIDER CHOCOLATE DELIVERED BY A SHORT FAT GRAY NON ECONOMIST AS A SUITABLE SUBSTITUTE?

I am highly elastic when it comes to chocolate consumption.

The major innovations of late appear to be focused on service and delivery – that is, the distribution of hearing aids as well as initial and follow-up audiologic evaluation and programming is going to increasingly happen over the web. It’s not perfect yet (new innovation rarely is), but over time technology will fill in the gaps. Despite the fact that the brick and mortar audiology industry will continue to fight this tooth and nail, the hearing aid market is on the verge of a major disruption which will render any economic models based on the current market structure obsolete.

I agree to some extent, unfortunately. I’d say maybe within a decade.

I envision people going to their local pharmacy kiosk and being fit by a minimum-wage, minimally-trained, “technicians”. Then people will get strapped-in (wired or wirelessly) and connect with computer software to determine their personal listening preference… Sadly, people are demanding this whether they realize it or not, when they demand ‘super-low’ priced hearing aids… takes the people who are most qualified (AuDs) to provide not only the fitting, but the incredibly important follow-up care and rehab, completely out of the picture.

Audiologists need to be prepared for this.