Downstream Consequences of Aging is a bi-monthly series written by guest columnist Barbara Weinstein, PhD.

Audiologists are obligated under the 2016 Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), which now includes domains of function directly related to age related hearing loss including depression. Last post iterated the prevalence of depression and hearing loss in the US aging population; the cost burden of the conditions; epidemiological data linking the conditions; and ideation of public policy initiatives for prevention and control of these linked, chronic conditions of aging.

Today’s post builds on the HI-depression relationship by introducing evidence of two related links that make the case for a public policy initiative for clinical treatment:

- Self-rated significant hearing handicap (HH) is an independent factor associated with severity and development of depressive symptoms.

- Even minimal daily use of hearing aids is associated with significantly lower likelihood of having depressive symptoms.

Hearing Handicap (HH) and Depression

Presence of self rated psychosocial hearing difficulties, measured using the Hearing Handicap Inventory (HHI), is associated with severity and development of depressive symptoms.

Saito et al. (2010)

As part of an ongoing community-based cohort longitudinal study of functional health of community based residents of a city outside of Tokyo without baseline depression, Saito et al. (2010) explored incident depression (after three years) based on baseline scores on the Screening Version of the Hearing Handicap Inventory (HHI-S). The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) was used to identify depressive symptoms.

Participants with significant hearing handicap (HH) had a higher incidence of depressive symptoms (19.6%) than did persons without (8.0%) self rated psychosocial hearing difficulties. As compared to participants without, subjects with HH had an increased odds of reporting depressive symptoms after adjusting for numerous covariates including age, smoking status, current history of major illness, and measured vision impairment.

Even after controlling for hearing loss severity, HH remained an independent predictor of future occurrence of depressive symptoms. Interestingly, when excluding hearing aid users from the multivariate analysis, HH remained associated with depressive symptoms at the three year follow up.

Gopinath et al. (2012)

Based on data from the population based Blue Mountain Hearing Study, Gopinath et al. (2012) also found that as compared to persons without HH according to responses to the HHI, older adults with self reported psychosocial hearing difficulties were more likely to have depressive symptoms. This association remained after adjusting for age, sex, walking disability, receipt of pension payment, use of community support, living arrangements, cognitive status, and history of arthritis and/or stroke.

Do Hearing Aids Matter?

Based on responses to the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10) participants in the Blue Mountains Study who reported using a hearing aid for a minimum of 1 hour per day had a significantly lower likelihood of having depressive symptoms than non-frequent users. According to scores on the CES-D-10, women who reportedly used their hearing aid frequently were less likely to suffer from depressive symptoms than women who used their aid infrequently even after adjusting for potential confounders (Gopinath, et al., 2009).

In their analysis using the NHANES data, Mener, et al., (2013) found that hearing aid use was associated with lower odds of major depressive disorder (MDD).

In their single arm prospective study, Boi, et al. (2012) also noted a significant reduction in depressive symptoms according to scores on the CES-D one month following the hearing aid fitting which remained after six months of hearing aid use.

Why and How To Screen for Depression?

Hearing-impaired persons have a 3-fold higher risk of developing social and emotional deficits in everyday life and 2/3 of older adults with measured hearing impairment at baseline develop psychosocial hearing difficulties within five years (Gopinath, et al., 2009). The symptoms of depression often overlap with those of handicapping hearing loss (e.g. loss of interest in activities, fatigue), hence screening for depression (as is part of PQRS) and referring older adults with age related hearing loss who fail the screen is in my view a professional obligation with which we must become comfortable.

Contributing to early recognition of depressive symptoms, intervening with hearing aids which can be effective in improving symptoms associated with depression, and documenting the efficacy of our hearing healthcare solutions is likely to contribute to increased recognition of our value as health care professionals. Improved collaborations with stakeholders in the geriatric network resulting from recognition of the contributions of our services to quality of life is a likely outcome.

We have a responsibility to advise our patients and physicians of screening results so that they can facilitate and coordinate referrals for mental health treatment. We do not want to miss opportunities to help improve health outcomes when a costly chronic condition such as depression is under-recognized and under-treated.

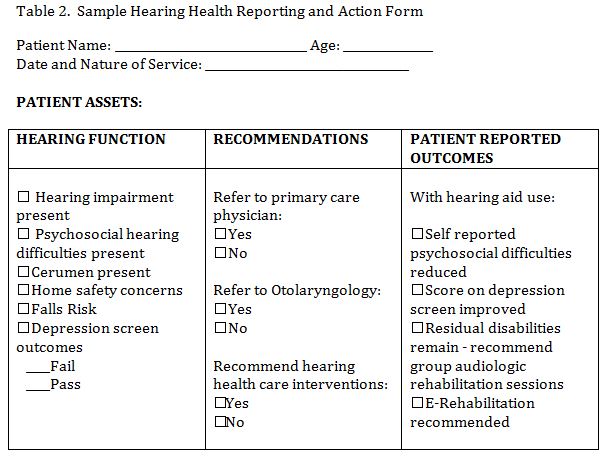

Table 1 includes a listing of reliable and valid measures of depression which relate to hearing status and Table 2 includes a sample form for communicating outcomes.

Table 1. Sample Tools for Screening or Measuring Depression

| Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale (CES-D) | Radloff (1977) |

| Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) | Spitzer, et al. (1999) |

| Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) ultra brief depression screener | Arroll et al. (2010) |

| The Mental Health Index

(a component of the SF-36 ) |

Friedman et al. (2005)

|

| Geriatric Depression Scale-Short Form (GDS-SF) | Sheikh & Yesavage (1986) |

Conclusion

Hearing impairment and associated psychosocial difficulties is a modifiable risk factor with hearing aids proving efficacious in reducing symptoms of depression. Let’s embrace the PQRS mandate and take advantage of the opportunity to potentially contribute to reduction in depressive symptoms and improving quality of life of older adults using the technologic advances at our disposal. Importantly, we must share the outcomes with the patient and physicians as the bi-directional benefits will be invaluable. As eloquently stated by Boi, et al. (2012):

“technological advances in hearing aids and exemplary customer care might do more than improve hearing capacity ……….. The mood, social life, general health and overall mental profile of patients also stand to benefit (p. 444).”

References

Arroll, B., Goodyear-Smith, F., Crengle, S., Gunn, J. et al. (2010). Validation of PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 to screen for major depression in the primary care population. Ann Fam Med. 8:348-53.

Boi, R., Racca, L., Cavallero, A., et al. (2012). Hearing loss and depressive symptoms in elderly patients. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 12:440–445.

Friedman, B,. Heisel, M., & Delavan, R. (2005). Validity of the SF-36 five-item Mental Health Index for major depression in functionally impaired, community-dwelling elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 53: 1978–85.

Gopinath, B., Wang, J., Schneider, R., et al., (2009). Depressive symptoms in older adults with hearing impairments: the Blue Mountains study. J Am Geriatr Soc.. 57: 1306-1308.

Gopinath, B., Hickson, L., Schneider, J., McMahon, C., et al., (2012). Hearing-impaired adults are at increased risk of experiencing emotional distress and social engagement restrictions five years later. Age and Ageing. 41: 618–623.

Hoyl, M., Alessi, C., Harker,J., et al. (1999). Development and testing of a five-item version of the Geriatric Depression Scale. J Am Geriatr Soc ;47:873–878.

Mener, D. Betz, J., Genther, D., & Lin, F. (2013). Hearing loss and depression in older adults. Journal American Geriatrics Society. 61: 1627-1629.

Radloff , L (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1: 385–401.

Sheikh, J., &, Yesavage, J. (1986). Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS). Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol. 5: 165–172.

Saito, H., Nishiwaki, Y., Michikawa, T., et al., (2010). Hearing Handicap Predicts the Development of Depressive Symptoms After 3 Years in Older Community-Dwelling Japanese. J Am Geriatr Soc. 58:93–97.

Spitzer, R., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. (1999). Validation and utility of the self- report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. JAMA. 282:1737–1744.

Barbara E. Weinstein, Ph.D. earned her doctorate from Columbia University, where she continued on as a faculty member and developed the Hearing Handicap Inventorywith her mentor, Dr. Ira Ventry. Dr. Weinstein’s research interests range from screening, quantification of psychosocial effects of hearing loss, senile dementia, and patient reported outcomes assessment. Her passion is educating health professionals and the public about the trajectory of untreated age-related hearing loss and the importance of referral and management. The author of both editions of Geriatric Audiology, Dr. Weinstein has written numerous manuscripts and spoken worldwide on hearing loss in the elderly. Dr. Weinstein is the founding Executive Officer of Health Sciences Doctoral Programs at the Graduate Center, CUNY which included doctoral programs in public health, audiology, nursing sciences and physical therapy. She was the first Executive Officer the CUNY AuD program and is a Professor in the Doctor of Audiology program and the Ph.D. program in Speech, Language and Hearing Sciences at the Graduate Center, CUNY.

feature photo courtesy of shannon christy (edit)