by Kate Baldocchi, AuD, Trisha Milnes, AuD, & Amyn M. Amlani, PhD

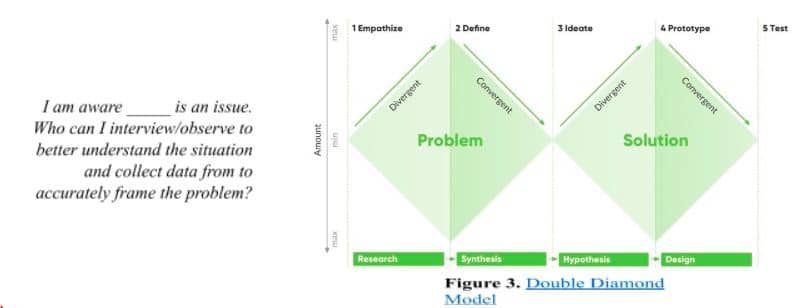

In 2019, the reader was introduced to a conceptual overview of the design thinking process and how it could be utilized as a tool in serving the needs of listeners with hearing loss. Design thinking engagement and interactions are comprised of a non-linear, 5-stage process that includes the areas of Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype, and Test.1

In a follow-up blog, readers were presented the first stage of design thinking: Empathize. Through interviews and observation, the Empathize phase allows for people we serve to be viewed from a new perspective. Looking beyond what is observed in the clinic and shifting focus to what occurs before and after the clinical evaluation facilitates “out-of-the-box” or “outside the sound booth” thinking.

In today’s blog, we review the second stage of the nonlinear process: Define. In the Define stage, data from the Empathize phase are synthesized and interpreted to uncover insights from the target audience. From these insights, an actionable, defined problem prompts, “how might we” questions for the third, or Ideate, phase.2 We will cover the Ideate phase in a future blog.

The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, has forced hearing healthcare to define the question of “how might we,” as it relates to:

- Serving patients when audiology is categorized as non-essential and businesses were mandated to temporarily close;

- Protecting employees and operations when private practice revenue is markedly constrained;

- Appling modified service delivery, such as telehealth/remote care; and

- Reducing exposure to patients, staff, and our families.

Reframing How We Define the Problem

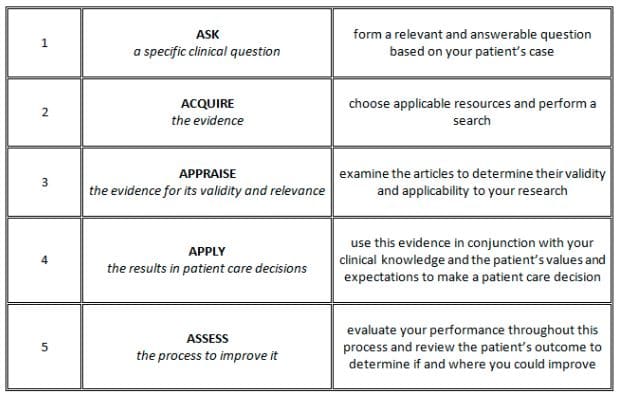

In health care, treatment decisions about patient care are often based on the evidence-based practice (EBP) model. EBP lies at the intersection of clinical expertise, patient values, and the best scientific evidence, and is a reliable and valid approach to problem-solving. Figure 1 illustrates the basic tenets of the EBP process. Note that EBP is predicated on a linear process, grounded on asking a specific question based on patient behavior or outcome to a treatment. The following steps in this process involve acquiring and appraising existing evidence, followed by applying the evidence to a real-world situation, and then assessing changes in patient behavior or outcome.

While EBP allows the provider to engage in high-quality care backed by empirical evidence, the linear structure of the model, unfortunately, falls flat in providing insights or determining solutions to wicked problems that require complex, radical intervention and agility. In addition, EBP is primarily literature focused, while design thinking is human-centered.3

Applying Design Thinking

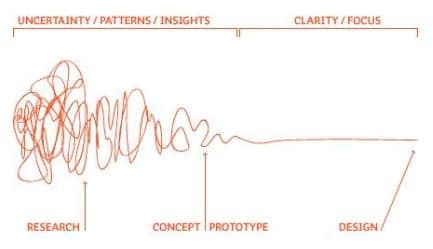

For most individuals new to the design thinking process, the process might feel or look chaotic (Figure 2). Even designers recognize the sense of chaos in the process:

Figure 2. Damien Newman, The Design Squiggle

Figure 3 illustrates that the design thinking process operates using a structured, double-diamond model predicated on exploring an issue more widely or deeply (i.e., divergent thinking) and then taking focused action (i.e., convergent thinking). The first diamond helps people who collaborate in groups understand—rather than assume—what the problems are (i.e., divergent thinking). This insight lends to defining the issue in a different way to the traditional approach of problem solving (i.e., convergent thinking). The second diamond encourages participants to provide separate and distinct responses to the defined problem, this time seeking inspiration from elsewhere and co-designing with different people (i.e., divergent thinking). These newly defined responses are then tested to determine those most likely to lessen the problem (i.e., convergent thinking).

Identifying and Defining Themes

The Define phase consists of the design team collaborating to synthesize the Empathize phase learnings, identify themes that emerge from the learnings, and uncover insights from these themes to ask, “How Might We” (HMW) questions. HMW questions are focused, brainstorming prompts for the next (i.e., third) phase in design thinking, Ideate.

The convergence of stakeholders’ stories, motivations, barriers and interactions turn learnings into “opportunities for design.”4

Visualize Learnings

Visualization…is any technique for creating images, diagrams, or animations to communicate a message. Visualization through visual imagery has been an effective way to

communicate both abstract and concrete ideas since the dawn of humanity.

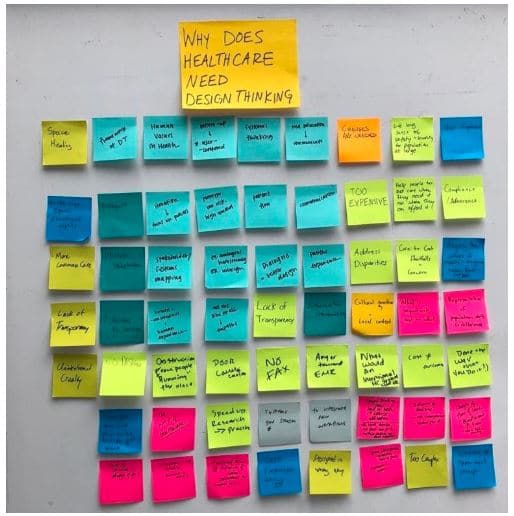

Data collected from the Empathize phase: photographs, quotes, body language observations, interesting stories, frustrations, and workarounds are each documented on Post-its: one point per Post-it Note.5 These data points can be organized using tools such as personas, empathy maps, or journey maps. The shared canvas of design thinking teams has historically been large whiteboards filled with Post-it Notes.

In 2020, travel restrictions and remote work has amplified the use of virtual whiteboards. This collective, visual approach to displaying data allows for easier theme identification from team members.

Bon Ku, MD MPP @BonKu. Tweet: #MedX Design Workshop: Why does healthcare need design thinking & barriers to design in #meded.

In their 2020 book, Health Design Thinking, Dr. Bon Ku and designer Ellen Lupton state, “Visualizing ideas and information is a bedrock of design practice.” Hearing health providers’ dependency on the audiogram as a basis for diagnosis and treatment plans reflect the power of visuals. What other data could we visualize to innovate how we care for our clients?

Visuals can ease the process of uncovering trends, making connections, combating biases, and identifying knowledge gaps. (Note: Dr. Bon Ku is a keynote speaker for the upcoming AuDacity 2020 Virtual Conference hosted by the ADA. Dr. Ku’s talk is scheduled for Friday, October 16.)

Collaborative Data Synthesis to Uncover Themes and Insights

Once data points have been captured and displayed across a single whiteboard, the team can start instinctively to observe trends from the interviews and observations. The common data points are clustered together, and groups are named by the common content, also known as themes. Each theme can generate multiple insight statements.4

“Insights are a succinct expression of what you have learned from your field research activities.

Insights offer a new perspective, even if they are not new discoveries.”

– Acumen Academy, Introduction to Human-Centered Design

A goal in design thinking is to refrain from making unfounded decisions or leaving future outcomes to chance. The process of empathizing with clients, observing clients, synthesizing and interpreting this data lays the groundwork for accurate problem identification. The journey map tool visualizes the diverse perspectives of stakeholders and reveals the barriers when experiencing a product or service. Individual barriers are parsed out as specific components of the whole practice to prioritize and converge themes.

Given the effect of COVID-19, incorporating the observation component could provide valuable insights into understanding how listeners with hearing loss perceive the risks associated with the virus, their willingness to engage in hearing health services, and the degree to which they socialize. The collaborative insights of a hearing health provider, hearing health patient, the patient’s spouse/family, referring provider and clinic staff would assemble an ideal design team for further investigation on the current state of hearing care.

As an example, consider the University of Texas Dell Medical School Design Institute for Health’s (DIH) case study on COVID-19 Drive-Thru Testing. In this case study, a team of healthcare professionals were asked to identify challenges and opportunities to improve the workflow design and enable scaling of these types of testing sites in the context of limited supplies.6

Themes that emerged included:

-Screening

-Intake

-Collection

-Processing

-Consultation

-Education

Insight that surfaced included:

“Reduce errors and increase speed by limiting the task complexity for any one person:

Rather than expecting a provider to learn several new tasks in this rapidly evolving workflow,

streamline a person’s tasks so they can focus and master them quickly.

This also improves the provider’s confidence in delivering a new service under duress that reduces anxiety and allows them to deliver care confidently and with empathy.”6

Note the design thinking insight statement focuses on the users and their needs while resisting the inclusion of “technology, monetary returns or product specifications.”2 This may sound like a counter-intuitive business strategy. However, by doing so, confirmation bias is kept in check and an environment for human-centered innovative ideas to flourish is created.

Successfully executed design thinking projects exist at the intersection of feasibility, viability, and desirability.7 Financial risks and time-to-market can both be reduced, while project ROI can significantly increase:

“Organizations slashed the time required for initial design and alignment by 75%.

The model demonstrates cost savings of $196K per minor project and $872K per major project.”

The Total Economic ImpactTM Of IBM’s Design Thinking Practice

HMW: Questions for the Ideate Phase

Design thinking has two phases (i.e., Empathy, Define) prior to the response most of us immediately have when presented with a problem: idea generation (i.e., delivering solutions). By taking the time to empathize with the people we serve, define problems as a team through theme identification and insight discovery, we now have the groundwork to ask impactful questions that reflect our patients’ needs, motivations and hopes.

“Avoid brainstorming questions that already imply a solution.”

– Acumen Academy, Introduction to Human-Centered Design

From each insight, generate multiple HMW questions that prompt multiple, unrestrained solutions.

Returning to the DIH COVID-19 Drive Thru Testing case study, here is one of their HMW questions:

HMW Example:

“How might we improve and evolve a rapidly-devised COVID-19 testing site workflow

to prepare for increased volume and scale?”6

Select the top three HMW questions that immediately inspire ideas3 from the team and get your virtual post its ready. The Ideate phase is where quantity and variety of ideas are highly encouraged.

Summary

Cognitive biases can lead to irrational behavior.8 Defining problems amongst irrational behavior, regardless of which stakeholder exhibits the behavior—patient, provider or manufacturer—can feel abstract. For abstract challenges, we need abstract tools, as provided by design thinking methodologies.

Synthesis consists of visualizing and organizing data from the Empathize phase. Synthesizing data collected from interviews and observations is similar to binaural loudness summation: in design thinking, summating multiple perspectives enhances the number of innovative ideas generated.

“Creative thinking…refers to how people approach problems and solutions—their capacity to put existing ideas together in new combinations…Her creativity will be enhanced further if she habitually turns problems upside down and combines knowledge from seemingly disparate fields.”

–How to Kill Creativity, Teresa Amabile HBR

References:

- Dam RF, Teo YS. (2020). 5 Stages in the Design Thinking Process. Interaction Design Foundation.

- Dam RF, Teo YS. (2020). Stage 2 in the Design Thinking Process: Define the Problem and Interpret the Results. Interaction Design Foundation.

- Howard Z, Davis K. (2011). From solving puzzles to designing solutions:Integrating design thinking into evidence based practice. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice 6(4):15-21.

- Acumen Academy. Introduction to Human-Centered Design. https://www.acumenacademy.org/course/design-kit-human-centered-design

- IDEO. Insights for Innovation. https://www.ideou.com/products/insights-for-innovation

- Designing on the Front Lines: COVID-19 Drive-Thru Testing (April 2020). Design Institute for Health. https://www.designinhealth.org/designing-on-the-front-lines-covid-19-drive-thru-testing

- Dam RF, Teo YS. (2020). From Prototype to Product: Ensuring Your Solution is Feasible and Viable. Interaction Design Foundation.

- Kahneman D, Tversky A (1972). “Subjective probability: A judgment of representativeness.” Cognitive Psychology. 3 (3): 430–454.

- Ku B, Lupton E (2020) Health Design Thinking: Creating Products and Services for Better Health

About the Authors

Kate Baldocchi, AuD, is a Government Account Manager at Phonak, designer and audiologist residing in Austin, TX. Dr. Baldocchi is a proponent of human-centered design in hearing healthcare, who envisions design as a vehicle for innovation that can help improve the lives of impaired listeners and the approaches providers utilize in service provision

Trisha Milnes, AuD, CCC-A, AIB-VAM is Chief of Audiology and Speech Pathology Services at Charlie Norwood VA Medical Center in Augusta, GA. She has completed the American Institute of Balance’s Certification in Vestibular Assessment and Management and Acumen Academy’s Introduction to Human Centered Design. Dr. Milnes enrolled in the Master of Healthcare Administration program through Colorado State University: Global Campus to develop leadership skills and networks to grow audiology and speech pathology into more prominent roles in medical settings by emphasizing the foundations of health that our services provide including communication resources, balance assessment and support, and cognition care in addition to initiating opportunities for growth through identification and prevention of hearing loss and fall risk through electronic health record identification factors.

Amyn M. Amlani, PhD, is the Director of Professional Development & Education at Audigy, a data-driven, management group for audiology and hearing care, ENT group, and allergy practices in the United States. Prior to this position, Dr. Amlani was an academician for nearly two decades. He also serves as section editor of Economics for Hearing Health Technology Matters.