The end of the year is usually a time of reflection and appreciation – for how far we have come from the dreaded days of disease that could snuff out a life before it got started and for the contributions to knowledge by those that suffered deafness through disease.

Scarlet fever (also known as Scarlatina), with its pandemics in both Europe and the United States in the 19th and early 20th centuries, was one of these killers, inflicting death on thousands of infants and young children. Simply hearing the name of this dreaded disease, or knowing that it was present in the community, was enough to strike fear into the hearts of those living in Victorian-era United States and Europe. In the worst cases, all a family’s children were killed in a matter of a week or two through contagion.

Indeed, until early in the 20th century, scarlet fever was a common condition among children. Scarlet fever, even when not deadly, caused large amounts of suffering to those infected and their families, often leaving deafness in its wake.

To put this disease in perspective, infant mortality rate is calculated by dividing the number of infants that die within one year of birth by the number of infants that are born. It is usually presented in the number of deaths per 1000 births. Prior to 1900 infant mortality rates of 2-300 per 1000 were common throughout the world, fluctuating according to the weather, the harvest, war, and epidemic disease. In difficult times, most infants would die within the first year of life, while under the best of conditions perhaps 200 per 1000 would die. In some pre-modern countries, child mortality rates were between 300 and 500 per 1,000 live births. In fact, in the late 19th century, every second child in Germany died before its fifth birthday.

Smith (2011) presents historical scarlet fever death data from Krause (1992) depicting Boston, Massachusetts (USA) during the period 1840-1940 which is typical of most pre-modern cities. These data suggest at least three epidemiologic phases during this time, not unlike the rest of the world during this pandemic. While the first major epidemic appears to have begun in ancient times and lasted until the late eighteenth century, scarlet fever was either endemic (always present at a low level) or occurred in relatively benign outbreaks separated by long intervals. In the second phase (~1825-1885), scarlet fever suddenly began to recur in cyclic and often highly fatal urban epidemics. In the third phase (~1885 to the present), scarlet fever began to manifest as a milder disease in developed countries, with fatalities becoming quite rare by the middle of the 20th century. This was mostly due to antibiotics and improved living conditions in these modern cities. In both England and the United States, mortality from scarlet fever decreased beginning in the mid-1880s and by the middle of the twentieth century, the mortality rate from scarlet fever fell to around 1%.

Those that have had children grow up in their homes will appreciate the number of times they may have become infected with a close relative to scarlet fever–“Strep Throat”. Even in 2016, “strep” is still a relatively common disorder among infants and young children, especially in day care centers and other child care situations. Scarlet fever and strep throat are caused by the same bacterium, Streptococcus pyogenes, or group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus. When the bacteria release toxins, scarlet fever symptoms occur. Scarlet fever transmits from human-to-human by fluids from the mouth and nose. When an infected individual coughs or sneezes, the bacteria become airborne in droplets of water and can be inhaled. The bacteria can land on surfaces, such as drinking glasses, work surfaces, and doorknobs, and infect people who touch them with their hands and then touch their own nose or mouth. The bacteria may also be inhaled.

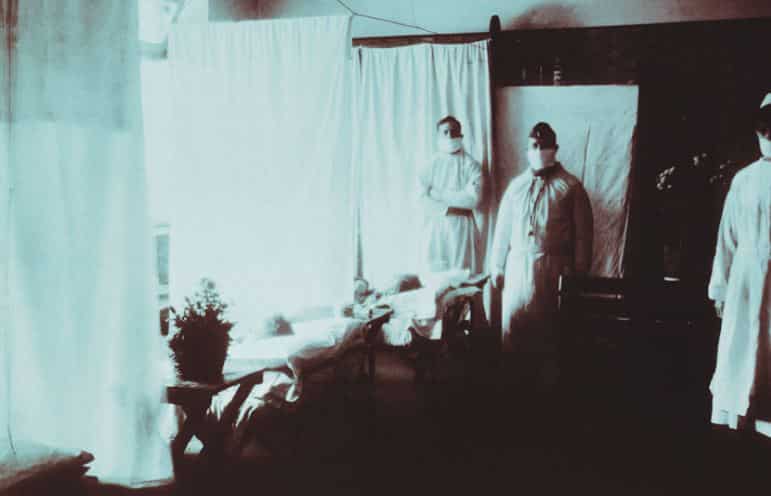

If someone touches the skin of an individual with a streptococcal skin infection, there is a risk of becoming infected. People who share towels, baths, clothes, or bed linen with an infected person are at risk. The early part of the Industrial Revolution probably exacerbated these conditions. At the time of the 19th and early 20th century pandemics, housing in factory cities was crowded, dirty, unheated, and unventilated. Even in Europe and the United States, food supplies, especially milk products were unreliable, impure, and so narrowly nutrition-based that these terrible conditions probably greatly increased the incidence of this and other disorders. At the time, diseases were generally untreatable, sometimes even unrecognized. Without a germ theory of disease, people did not know to take precautions to prevent the spread of infectious diseases. A person with scarlet fever who is not treated may be contagious for several weeks, even after symptoms have gone. Additionally, some individuals can carry the infection and be contagious, without ever showing any symptoms and only those who are susceptible to the toxins released by streptococcal bacteria develop symptoms.

Scarlet fever mostly affects children between ages 2 and 10 and often begins as a throat infection (strep throat), the fever (over 101 degrees) typically subsides within 3 to 5 days, and the sore throat passes soon afterward. The Scarlet Fever rash usually fades on the sixth day after sore-throat symptoms started. While there is no vaccine, the infection itself is usually cured with a 10-day course of antibiotics, but it may take a few weeks for tonsils and swollen glands to return to normal. Today, in most first world countries, the infection usually does not progress past the “strep throat” stage.

Auditory Implications: Hearing Loss and Deafness from Scarlet Fever

One of the serious results of scarlet fever was often deafness. The deafness usually arises from complications that include sinus infections, followed by abscesses of the ear and often resulting in mastoiditis. In scarlet fever, diphtheria, measles, and influenza, the middle ear is usually affected by communication with the nasopharynx through the Eustachian tubes. The inflammation extending along the Eustachian tube is followed by suppuration and perforation of the membrane resulting in a conductive hearing loss that would not be curable until many years later, if then. Sometimes the membranous labyrinth is affected directly creating cochlear damage due to systemic poisoning by the bacteria which would then leave a sensori-neural hearing loss.

Additionally, a sustained high fever of over 104 degrees which may accompany the disorder can also create a sensorineural hearing loss and require immediate medical attention. Most parents were grateful that their child’s life was spared, but the residual damage was an auditory devastation that destined many of 19th and early 20th century children to a life of deafness or being hard of hearing.

“One of the serious results of scarlet fever was often deafness. The deafness usually arises from complications that include sinus infections, followed by abscesses of the ear and often resulting in mastoiditis.”

These days scarlet fever issues created within the middle ear and the resulting conductive hearing loss can usually be surgically repaired or cured in most cases, or never occur with today’s antibiotic treatment regimes.

While deafness from scarlet fever was a devastation of the 19 and early 20th centuries a positive from this dreaded disease was the many inventions created due to its presence. These include surgical techniques, research into bacteria, even Miller Reese Hutchinson’s first hearing aid , which was made for a friend who had suffered the disease. Some of those deafened by scarlet fever became contributors to science, the arts and other disciplines, many of whom have been featured at Hearing International.

Just a small fraction of those that were affected by the disease are remembered here:

- Helen Keller – Deaf Blind Political Activist, and Lecturer

- Thomas Edison – Famous Inventor

- Oliver Heaviside – Famous Engineer, Mathematician, and Electric Circuit Theorist

- Konstantin Tsiolkovsky – Rocket Scientist and Aeronautic Theorist

- Douglas Tilden – World Famous Sculptor

- Granville Redmond – Landscape Painter, occasional actor with Charlie Chaplin

References:

Kress, H. (2016). Scarlett Fever. Henrietta’s Herbal Homepage. Retrieved December 26, 2016.

Roser, M. (2016) – ‘Child Mortality’. OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved December 26, 2016.

Smith, T. (2011). Scarlet Fever: Past and Present. Aeitology. Science Blogs.com Retrieved December 26, 2016