One of the first concepts learned in deaf education or aural rehabilitation courses is the controversy over sign language (manualism) vs. oralism. There is an undertone that oralism is better than manualism. It has been the root of much discussion in the deaf community as well as among educational and medical professionals since the inception of formal sign language in 18th century France.

On one hand communication with the hearing impaired through sign language offers a natural method for interaction and education for those that cannot learn verbal communication. For mothers and fathers of deaf children, the use of signing allows for the natural psychological development of children and promotes easy and normal family interactions. Signing, of course, is even used at the university level to learn and become successful in virtually every field. American Sign Language (ASL) and its derivatives is taught all over the world to both hearing and deaf individuals and has now become a popular second language for many hearing individuals.

On the other hand, the oralist argument is that deaf individuals must integrate into the hearing world to have opportunity outside the family and the deaf community which requires oral communication. While this argument does have some merit, not all deaf individuals are capable of communicating orally, even with today’s high technology.

While the newest technology such as cochlear and middle ear implants, the newest hearing devices, and 21st century education techniques have allowed for more oral communication among the deaf than ever before, the controversy still exists.

Even though there are tremendous personal, professional successes with each of these methods there has always been a general undertone that oralism is better than manual communication, but WHY, where did the notion that one system is better than another originate?

The First International Congress on Education of the Deaf

Due to the successes of teaching the deaf over 150 years, both orally and with sign language, there was great controversy in the late 19th century about which method should be used to educate and interact with the deaf. The oralists felt that their method was best and those that used sign language felt that their method was best.

It had been hotly contested for over a century which method – the manual method using sign languages or the oral method of lipreading and articulation – was the most effective.

The Pereire Society organized the first congress in Paris in 1878 to establish a standardized approach, but it was the Second International Congress on Education of the Deaf in Milan, Italy in 1880 that became the major platform for debates and significant resolutions on the matter.

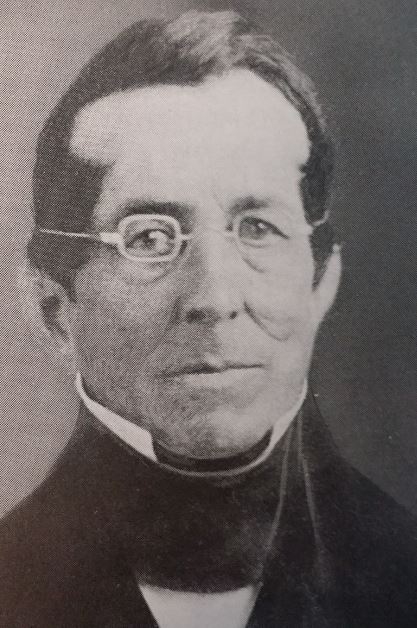

Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet. Image credit, Wikipedia

Representatives of the Pereire Society were interested in bringing about a standardized method for education of the deaf via the oral method. This first congress was held in Paris in 1878, and was attended by 28 delegates from 6 countries: France, Sweden, Italy, Austria, Belgium and the United States (but only as an observer). As in other areas of endeavor, dealing with deep seated emotions and philosophies that had developed over a century or so were difficult to discuss with civility and it appears that nothing much was resolved at the first meeting.

It appears that the place where the major debates occurred and far reaching resolutions were adopted was at the Second International Congress on Education of the Deaf in Milan Italy, 1880.

The Second International Congress on Education of the Deaf: “The Milan Conference”

Burke (2014) indicates that the notion of the superiority of oral methods began at the famous Second International Congress on Education of the Deaf held September 6-11, 1880 in Milan, Italy.

This conference was attended by representatives from more countries than the previous one and offered some discussion of manual as well as oral methods. There were 164 members (142 of which were either British or Italian) representing eight different countries and were champions of both oral and manual methods. On one side was Alexander Graham Bell and his colleagues from around Europe supporting the oral methods and on the other side was Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet and colleagues from the US and Britain supporting the manual methods. Only one representative was deaf, James Denison a member of Gallaudet’s US delegation.

While the Americans and the Brits did their level best to counteract the air of oral method superiority, the oralists won this round and the Milan Congress adopted 8 resolutions, two of which had an astronomical impact on deaf education.

Those far reaching resolutions were:

1. The Convention, considering the incontestable superiority of articulation over signs in restoring the deaf-mute to society and giving him a fuller knowledge of language, declares that the oral method should be preferred to that of signs in the education and instruction of deaf-mutes.

2. The Convention, considering that the simultaneous use of articulation and signs has the disadvantage of injuring articulation and lip-reading and the precision of ideas, declares that the pure oral method should be preferred.

According to the consensus (of hearing people at the conference), the “superiority of speech over signs would aid in restoring deaf-mutes to social life” and provide a “greater facility of language.” At the conclusion of the Milan Conference, the oral method was voted to become the officially acknowledged method for instructing the deaf. According to Burke (2014) there were immediate consequences of the Milan resolutions:

- Deaf Teachers lost their jobs.

- The fledging National Association of the Deaf attracted more supporters as the deaf people fought to save their language and culture.

- The President of Gallaudet College at the time decided to keep sign language on the Gallaudet campus (which survives today). It is thought that this decision may have been largely responsible for the survival of American Sign Language.

In all fairness to the 1880 deaf education decision makers, 19th century hearing aids were only mechanical and extremely crude, cochlear implants were an impossible dream but not many people in the general worldwide population knew sign language. Deafness was also more common at this time as there were no antibiotics, infection control procedures to reduce epidemics, or successful surgeries that cured deafness. Thus, some solutions were necessary to facilitate education, with two vastly different approaches to the process.

Some felt that the Milan conference was tainted as many of deaf educators of the time were manual deaf as well, these individuals were virtually excluded from the conference and many lost their jobs in the aftermath. Consequently, critics have suggested that with minimal discussion of all the major education techniques, the conference was unfair to manual methods leaving it as mere propaganda for oral (lipreading) techniques. Championed primarily by the representatives from the United States and Britain, this so called consensus and resolutions from the Milan Conference sparked an enormous amount of controversy and further established the much-heated manual vs. oral “war of methods” that would last well over a century.

In modern times, however, oralists and manualists have learned to live with each other, allowing the deaf community decide the methods used in education.

References:

Burke, J. (2014). Deaf History- Milan 1880: Event with powerful repercussions. www.verywell.com. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

Gallaudet University (2005). Collection of International Congress on the Education of the Deaf, 1963. Gallaudet University Deaf Collections and Archives. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

Jowers-Barber, S. (2011). The complicated history of deaf education. New York Times: Opinion Pages, Room for Debate. Retrieved May 31, 2016.