Stanton (2016) indicates that the history of deaf and hard of hearing lawyers parallels the history of deaf and hard of hearing people in general. As technology progressed, and as accessibility laws were enacted, the opportunities for deaf and hard of hearing lawyers (and deaf and hard of hearing people in general) increased and the barriers faced by them were broken. In 2016, Stanton reported that there were about 30 deaf and hard of hearing attorneys in the United States. Today there is even a Deaf and Hard of Hearing Bar Association (DHHBA) is an organization of deaf, hard of hearing, and late-deafened attorneys, judges, law school graduates, law students, and legal professionals. They are a member-focused organization, providing a forum for the exchange of ideas, building relationships, and informal mentoring. Members of the DHHBA have all types and degrees of hearing loss and use all types of communication methods and accommodations. It was not always easy to be an attorney with hearing impairment. In a profession that prides themselves on communication, questions, interaction with clients and other skills necessary for counselors, deafness one really a barrier. In 2011, there was only a handful of deaf lawyers who were admitted to the United States Supreme Court Bar and by 2016, there are over thirty. It is only a matter of time before its routine for a deaf or hard of hearing attorney to argue cases before the U.S. Supreme Court.

Stanton (2016) indicates that the history of deaf and hard of hearing lawyers parallels the history of deaf and hard of hearing people in general. As technology progressed, and as accessibility laws were enacted, the opportunities for deaf and hard of hearing lawyers (and deaf and hard of hearing people in general) increased and the barriers faced by them were broken. In 2016, Stanton reported that there were about 30 deaf and hard of hearing attorneys in the United States. Today there is even a Deaf and Hard of Hearing Bar Association (DHHBA) is an organization of deaf, hard of hearing, and late-deafened attorneys, judges, law school graduates, law students, and legal professionals. They are a member-focused organization, providing a forum for the exchange of ideas, building relationships, and informal mentoring. Members of the DHHBA have all types and degrees of hearing loss and use all types of communication methods and accommodations. It was not always easy to be an attorney with hearing impairment. In a profession that prides themselves on communication, questions, interaction with clients and other skills necessary for counselors, deafness one really a barrier. In 2011, there was only a handful of deaf lawyers who were admitted to the United States Supreme Court Bar and by 2016, there are over thirty. It is only a matter of time before its routine for a deaf or hard of hearing attorney to argue cases before the U.S. Supreme Court.

The First Deaf Attorney to Argue a Case

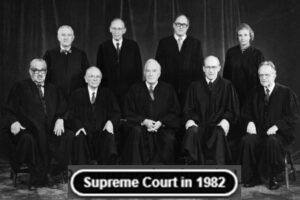

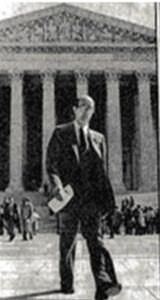

Probably among the most famous deaf attorneys is a 1971 graduate of the Brooklyn Law School graduate, New York attorney, Michael A. Chatoff, (1946-2007) at age 35, was the first deaf attorney to argue a case to the United States Supreme Court in 1982. Specialized in Civil Rights and Education, Chatoff  represented young Amy Rowley and her family to the highest court in the land, it was March 23, 1982 when a stirring plea on behalf of a 10-yearold deaf girl from northern Westchester County, a 35-year-old graduate of

represented young Amy Rowley and her family to the highest court in the land, it was March 23, 1982 when a stirring plea on behalf of a 10-yearold deaf girl from northern Westchester County, a 35-year-old graduate of Brooklyn Law School today became the first deaf lawyer to argue before the United States Supreme Court. Personal information and photos on Chatoff are scarce, but it is known that he lost his hearing from a virus that he suffered while in law school. Thus, His speech was very good, but he required special assistance to understand the Court’s questions.

Brooklyn Law School today became the first deaf lawyer to argue before the United States Supreme Court. Personal information and photos on Chatoff are scarce, but it is known that he lost his hearing from a virus that he suffered while in law school. Thus, His speech was very good, but he required special assistance to understand the Court’s questions.

The Facts of the Case in Question

Amy Rowley was a deaf student enrolled in kindergarten in public school in Peekskill, New York. She was the deaf child of deaf parents who simply wanted the best education possibly for their child. Most audiologists will realize that this case is really a case of supporting Deaf Culture as much as it is for education. The school wanted the child to be taught orally while the parents wanted her to be part of their culture, the Deaf. It seems that free and appropriate education epelled out in the legalese of the case only applied to oral education, not manual.

Prior to the beginning of her kindergarten year, Amy’s parents met with school administrators to plan for her attendance and to determine what supplemental services would be necessary for her education. During a short portion of her kindergarten year, Amy was provided with a sign language interpreter in the classroom. Following a two-week trial period, the interpreter reported that Amy did not need his services in the classroom. After her kindergarten year, an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) was prepared for Amy. The IEP provided that Amy would remain in the regular classroom and would be provided with an FM wireless hearing aid in the classroom, and, additionally, she would receive instruction from a tutor for one hour a day and from a speech therapist for three hours per week outside of the classroom. Amy’s parents objected to portions of the IEP, requesting that the school provide Amy with a sign language interpreter instead of the other forms of assistance identified in the IEP. Sc hool administrators refused the request, concluding that Amy did not need an interpreter in the classroom. Amy’s parents sought administrative and judicial review of the school’s decision pursuant to the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EAHCA). The Rowleys argued that because Amy could only decode a fraction (approximately 60%) of the oral language available to hearing students in class, she was entitled to a sign-language interpreter. Without an interpreter, they argued, Amy would be denied the educational opportunity available to her classmates. After a hearing officer declared that Amy was entitled to an interpreter, the school board sought judicial review. A federal trial court in New York ruled, and the Second Circuit affirmed, that Amy was being denied the opportunity to achieve her potential at a level “commensurate with the opportunity provided other children”—a standard that echoed the regulations implemented for Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. lick on the Chatoff’s Picture (Lef) to hear his argument before the Court. Kleiman (1982) reported that Chatoff further

hool administrators refused the request, concluding that Amy did not need an interpreter in the classroom. Amy’s parents sought administrative and judicial review of the school’s decision pursuant to the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EAHCA). The Rowleys argued that because Amy could only decode a fraction (approximately 60%) of the oral language available to hearing students in class, she was entitled to a sign-language interpreter. Without an interpreter, they argued, Amy would be denied the educational opportunity available to her classmates. After a hearing officer declared that Amy was entitled to an interpreter, the school board sought judicial review. A federal trial court in New York ruled, and the Second Circuit affirmed, that Amy was being denied the opportunity to achieve her potential at a level “commensurate with the opportunity provided other children”—a standard that echoed the regulations implemented for Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. lick on the Chatoff’s Picture (Lef) to hear his argument before the Court. Kleiman (1982) reported that Chatoff further  presented in what was described as halting dissonant speech as the Justices leaned forward in their seats to be able to hear, ”This is a tough world, and it is going to be as tough for Amy as it is for every other child, if she’s going to be able to compete she must receive an education equal to those of other children.

presented in what was described as halting dissonant speech as the Justices leaned forward in their seats to be able to hear, ”This is a tough world, and it is going to be as tough for Amy as it is for every other child, if she’s going to be able to compete she must receive an education equal to those of other children.

Michael A. Chatoff, who could speak but not hear, communicated with the assistance of a computerized video display screen, communicating with the nine Justices during oral arguments by reading their questions on the video screen and then speaking back to them. In 1982 these were rather crude systems but the beginning of a new world for the deaf and hard of hearing. The system was specially installed in the Courtroom and worked with a stenotypist in the courtroom typed the argument into a computer system on a terminal set up in an adjoining corridor. The computer then translated the stenographic shorthand into English and almost instantly displayed the transcript on Mr. Chatoff’s screen. The system was developed by Gallaudet College, a national college for the deaf in Washington, not bad for a 1982, PC Jr. It was the first time the Court had permitted the use of special electronic equipment in the courtroom. It did so specifically for this case, in which it must decide whether a Westchester school district may be required by law to provide a sign-language interpreter for Amy Rowley, a deaf fourth-grade student from Cortlandt, N.Y., who was at the time, in the top half of her class. It was also the Court’s first opportunity to define what Congress meant in the Education For All Handicapped Children Act of 1975, which says that all handicapped children are entitled to a ”free appropriate public education.” As a result Amy Rowley remained in the first grade with all previous supplemental services and supports offered by the school district, but with no sign language interpreter. While Michael A. Chatoff lost his case by a ruling of 6-4……that day he became the history’s first deaf attorney to argue a case for the Supreme Court, beginning a new trend for deaf and hard of hearing attorneys that continues today.

And….What of Amy Today, Some 37 Years Later

And….What of Amy Today, Some 37 Years Later

Despite all the controversy in the 1980s, Amy June Rowley grew up to become quite successful. She is now, Dr. Amy June Rowley and is an Associate Professor of Modern Languages and Literature and also Coordinator of the American Sign Language Program at Cal-State East Bay in Hayward, CA. She completed her Ph.D. with a dissertation in 2014 in Second Language Education in Urban Education from the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee where she focused on American Sign Language Advanced Studies Programs: Implementation Procedures and Identifying Empowering Practices. She holds a professional level certification in American Sign Language Teachers Association (ASLTA). Her research interests are systemic and hierarchal structure of American Sign Language programs in postsecondary institutions; and relationships between students/interpreters and the Deaf community. She has published articles related to Audism, oppression and special education experiences. Prior to coming to Cal State- East Bay, she was the coordinator of the American Sign Language Program at the University of Wisconsin- Milwaukee for nine years.

References:

Deaf and Hard of Hearing Bar Association (2019). About DHHBA, Retrieved July 31, 2019.

Kleiman, D. (1982). First Deaf Lawyer Goes Before Supreme Court. New York times, March 24, 1982, Retrieved July 31, 2019.

Stanton, J. (2016). A Brief History of Deaf and Hard of Hearing Attorneys. Deaf and Hard of Hearing Bar Association, Retrieved July 30, 2019.

Supreme Court of the United States (1982). Chatoff oral argument in Board v Rowley.ogg, Retrieved July 31, 2019.

Wrights Law (2019). BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE HENDRICK HUDSON CENTRAL SCHOOL DISTRICT, WESTCHESTER COUNTY, et al.,

Petitioners v. AMY ROWLEY, by her parents, ROWLEY et al. Respondent, No. 80-1002, U.S. Supreme Court, Retrieved July 31, 2019.