The Potato Famine

In the 1830s-40s most of Ireland lived in terrible housing conditions. A census report in 1841 found that nearly half the families in rural areas lived in windowless mud cabins, most with no furniture other than a stool. Their pigs slept with their owners and heaps of manure lay by the doors. In the culture of the time, boys and girls married young, with no money and almost no possessions. They would build a mud hut, and move in with no more than a pot and a stool. When asked why they married so young, the Church would reply, “They cannot be worse off than they are and . . . they may help each other.”

Potatoes were unique in many ways. Large numbers of them could be grown on small plots of land. An acre and a half could provide a family of six with enough food for a year. They were nutritious, easy to cook, and could be fed to pigs, cattle and fowl. Poor families did not need a plough to grow potatoes, with a spade they could grow potatoes in wet ground and o

with enough food for a year. They were nutritious, easy to cook, and could be fed to pigs, cattle and fowl. Poor families did not need a plough to grow potatoes, with a spade they could grow potatoes in wet ground and o n mountain sides where no other kinds of plants could be cultivated. More than half of the Irish people depended on the potato as the main part of their diet, and almost 40 percent had a diet consisting almost entirely of potatoes, with some milk or fish as the only other source of nourishment. Potatoes, however, could not be stored for more than a year and, if the crop failed, there was nothing to replace it. Add to this intense poverty, the Irish Potato Famine of 1845-1852 created

n mountain sides where no other kinds of plants could be cultivated. More than half of the Irish people depended on the potato as the main part of their diet, and almost 40 percent had a diet consisting almost entirely of potatoes, with some milk or fish as the only other source of nourishment. Potatoes, however, could not be stored for more than a year and, if the crop failed, there was nothing to replace it. Add to this intense poverty, the Irish Potato Famine of 1845-1852 created  disaster. In 1845 an infestation of a fungus-like organism called Phytophthora infestans spread rapidly throughout Ireland ruining one-half of the potato crop that year, and about three-fourths of the crop over the next seven years.

disaster. In 1845 an infestation of a fungus-like organism called Phytophthora infestans spread rapidly throughout Ireland ruining one-half of the potato crop that year, and about three-fourths of the crop over the next seven years.

In the 1840s, Ireland was ruled by Great Britain as a colony. When the crops began to fail Irish leaders in Dublin petitioned Queen Victoria and Parliament to act—and, initially, they did, repealing the so-called “Corn Laws” and their tariffs on grain, which had made food such as corn and bread prohibitively expensive. These Corn Law and tariff changes, however, failed to offset the growing problem of the potato blight which tenant farmers relied upon heavily for food. With the costs of supplies rising many tenant farmers were unable to produce sufficient food for their own consumption. Before it ended in 1852, the Potato Famine resulted in the death of roughly one million Irish citizens from starvation and related causes. At  least another one or two million were forced to leave their homeland as refugees. Between 1820 and 1860, the Irish constituted over one third of all immigrants to the United States. In the 1840s, they comprised, during the famine nearly half of all immigrants to the United States.

least another one or two million were forced to leave their homeland as refugees. Between 1820 and 1860, the Irish constituted over one third of all immigrants to the United States. In the 1840s, they comprised, during the famine nearly half of all immigrants to the United States.

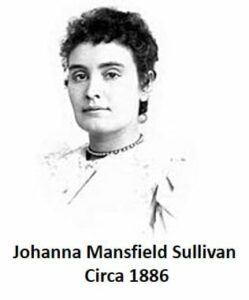

Among these frustrated Irish refugees were Thomas and Alice Sullivan from Limerick that emigrated to the United States. Along with other Irish comrades, the Sullivans settled in  the Feeding Hills Section of Agawam, in south central Massachusetts. Agawam contains a subsection, Feeding Hills where Line Street is generally accepted as the unofficial border. In the early to mid-19th century, a ditch was dug here to separate the two sections, likely to separate the refugees. The city of Agawam was quite rural at the time and the illiterate Thomas found work as a laborer. Thomas and Alice had their first child, Johanna Mansfield Sullivan on April 12, 1866 in Feeding Hills and later her brother James followed shortly thereafter. At about age five, Johanna contracted trachoma, an eye disease caused by bacteria. Trachoma usually begins in childhood

the Feeding Hills Section of Agawam, in south central Massachusetts. Agawam contains a subsection, Feeding Hills where Line Street is generally accepted as the unofficial border. In the early to mid-19th century, a ditch was dug here to separate the two sections, likely to separate the refugees. The city of Agawam was quite rural at the time and the illiterate Thomas found work as a laborer. Thomas and Alice had their first child, Johanna Mansfield Sullivan on April 12, 1866 in Feeding Hills and later her brother James followed shortly thereafter. At about age five, Johanna contracted trachoma, an eye disease caused by bacteria. Trachoma usually begins in childhood and causes repeated, painful infections, making the eyes red and swollen.

and causes repeated, painful infections, making the eyes red and swollen.

Over time the recurring irritation and scarring of the cornea causes severe vision loss. The effects of trachoma were significant issues for her in childhood and followed her throughout life. When Johanna was 8, in 1874, her mother died from Tuberculosis. Thomas became an abusive alcoholic. Finding it too difficult to raise a family by himself he soon abandoned his children.

Tewksbury Almshouse

Johanna and Jimmie were sent to live in the “poor house” in Tewksbury, Massachusetts, a few miles to the northwest of Boston. The true story of the Tewksbury Almshouse paints a grisly picture of the facility in the 1870’s and early 1880’s. Conditions there were dire as the place was overcrowded and underfunded, housing an average of 940 men, women and children. The facility was run by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and, indeed, was a place of horror.

In addition to the extreme overcrowding, atrocities revealed in State Hearings on the Almshouse included deliberate neglect, starvation, the sale of corpses, grave robbing, killing of infants by over-medication, housing inmates under horrid conditions, tanning of human skin, and theft of inmates’ clothing and possessions and of large quantities of bulk supplies.

Due to conditions and his weak hip, Jimmie passed away after only three months in this house of horrors. Johanna persevered for another four years at the Almshouse after her brother’s death with severe visual impairment. During an 1880 State Board of Charities inspection of the Tewksbury Almshouse, she persuaded inspector Franklin Benjamin Sanborn to allow her to leave the Almshouse and enroll in the Perkins School for the Blind in Boston where, Johanna at age 14 began her studies on October 7, 1880.

Although heaven compared to the Tewksbury Almshouse, Johanna had a hard time at school, constantly trying to overcome her terrible past, her mother death, being abandoned by a father, departure of siblings, death of a brother and whatever atrocities came from within the Almshouse. Initially, she tended to be arrogant and defiant, likely attitudes born of shame and a feeling of social inferiority. Gradually, several of the Perkins teachers took an interest and began to cultivate her sharp mind as they tried to understand the reasoning behind her hostilities and sharp tongue.

After several operations her vision was improved and with the encouragement of these dedicated teachers, her learning progressed at a rapid pace. Soon she was given the task of acting as a guide for other children. One of Joanna’s most useful accomplishments at Perkins was learning the deaf blind manual alphabet so she could talk to Laura Bridgman, the first deaf-blind child to be educated in the United States, a skill that was to serve her well in later years. Johanna graduated from high school at Perkins in 1886 as valedictorian of her class at age 20.

Meeting and Teaching Helen Keller

In 1886, Helen Keller’s mother was inspired by an account in Charles Dickens‘ American Notes that reported the successful education of Laura Bridgman, another deaf blind woman. As the story goes, she and her husband sought out Dr. J. Julian Chisolm, an eye, ear, nose, and throat specialist in Baltimore, for advice. who referred them to Alexander Graham Bell, who was working with deaf children at the time.

Bell advised them to contact the Perkins Institute for the Blind, the school where Bridgman had been educated, then located in South Boston. Michael Anagnos, the school’s director, asked his first choice for the position, 20-year-old former student, Johanna Mansfield Sullivan to become Keller’s instructor. Johanna moved to Tuscumbia Alabama to begin a 49-year-long relationship during which Sullivan evolved into Keller’s governess and eventually her companion. This began the lifetime teaching and personal relationship between Helen Keller and Johanna. Within two weeks offering young Helen a mixture of love and discipline she was able to establish some authority over the undisciplined child finally reaching her mind by using the sense of touch with the manual alphabet, spelling words in her hand.

Soon after they began, Helen discovered the correlation between words and objects. Anne used practical situations to show her this connection. The first time Helen made that connection was for the word “Teacher”, which is what Helen always called Johanna.

One famous lesson was when Johanna took Helen outside to the water pump. Anne started to draw water and put Helen’s hand under the spout. As the cool water flowed over one hand, she spelled the word “w-a-t-e-r” manually into the other hand. Suddenly, the signals had meaning in Helen’s mind. It was here that Helen learned that everything had a name and that the manual alphabet was the key to everything she wanted to know.

From then on, Keller was investigating various things and their names. The rest is the history of education of the deaf- blind presented in movies, and literature world wide. According to Biography (2019), with Johanna’s instruction, Keller learned nearly 600 words, most of her multiplication tables, and how to read Braille within a matter of months. News of Johanna’s success with Keller spread, and the Perkins school wrote a report about their progress as a team. Of course, Helen Keller became a celebrity because of the report meeting Thomas Edison, Alexander Graham Bell, and Mark Twain and other important people.

Later, despite the physical strain on her own limited sight, Johanna assisted Keller through her studies at Radcliffe College in 1900 where she spelled the contents of class lectures into Keller’s hand, and spent hours conveying information from textbooks. As a result, Keller became the first deaf-blind person to graduate from college.

This whole story is not about Helen Keller, but Johanna. She was never called Johanna, she always was Anne. Anne Sullivan, Helen Keller’s teacher, was a bold pioneer in the education of the deaf-blind and the result of her parents emigration to the United States due to the Irish Potato Famine. At right, is a shot of Helen and Anne about 1930. Anne and Helen were lifelong friends until her death in Queens, NY, October 20, 1936 at the age of 70.

This whole story is not about Helen Keller, but Johanna. She was never called Johanna, she always was Anne. Anne Sullivan, Helen Keller’s teacher, was a bold pioneer in the education of the deaf-blind and the result of her parents emigration to the United States due to the Irish Potato Famine. At right, is a shot of Helen and Anne about 1930. Anne and Helen were lifelong friends until her death in Queens, NY, October 20, 1936 at the age of 70.

References:

History .com Editors (2019). Irish Potato Famine. Retrieved June 10, 2019.

McGinnity, B.L., Seymour-Ford, J. and Andries, K.J. (2004) Anne Sullivan. Perkins History Museum, Perkins School for the Blind, Watertown, MA, Retrieved June 10, 2019.

Wallace, A. (2017). Anne Sullivan the Irish girl that taught Helen Keller to Speak. The Irish times, Retrieved June 10, 2019.