If you were not raised in Texas or live outside the US, this Texas hero may have escaped your history lessons. Erastus Smith was born in New York on April 19, 1787. In 1798, at age 11, his family moved to Port Gibson, Mississippi Territory (near Natchez) where he finished his formative years. According to Huston (1973), his parents were strict Baptists who thought morals and education were very important. The exact cause of the beginnings of his hearing loss is unknown, but thought to be from either birth or a childhood illness, young Erastus experienced a partial hearing loss. Childhood illnesses, of course, were rampant in the late 1700s all over America. Mortality was high for infants and small children, especially from diphtheria, smallpox, yellow fever, and malaria. Most sickness

If you were not raised in Texas or live outside the US, this Texas hero may have escaped your history lessons. Erastus Smith was born in New York on April 19, 1787. In 1798, at age 11, his family moved to Port Gibson, Mississippi Territory (near Natchez) where he finished his formative years. According to Huston (1973), his parents were strict Baptists who thought morals and education were very important. The exact cause of the beginnings of his hearing loss is unknown, but thought to be from either birth or a childhood illness, young Erastus experienced a partial hearing loss. Childhood illnesses, of course, were rampant in the late 1700s all over America. Mortality was high for infants and small children, especially from diphtheria, smallpox, yellow fever, and malaria. Most sickness  during this time was trusted to local healers that used folk remedies (Viets, 1935). At that time (1790s), the brand new US government was offering little control and regulation of medical care or attention to public health issues. The new country was just figuring out how to govern.

during this time was trusted to local healers that used folk remedies (Viets, 1935). At that time (1790s), the brand new US government was offering little control and regulation of medical care or attention to public health issues. The new country was just figuring out how to govern.

Smith was also sickly as a child and while living in Mississippi developed some long-term lung illness, at the time called consumption [these days called Tuberculosis]. Young Erastus went to Spanish Texas for a short time in 1817 as he was ill and needed a drier climate to recover from his disease. He returned home to Port Gibson upon his recovery but in 1821, at age 34, after Mexico’s War of Independence from Spain he returned to Texas for to stay. This is also a time when historians feel that he lost more of his hearing. Smith originally settled in Bexar, Tx (now part of San Antonio) where in 1822 he married a Hispanic-Texan (Tejana) a widow named Guadalupe Ruiz Duran. Reviewing family and Texas Army records, historians (Griffis, 1958; Huston, 1973) found that Erastus could converse face-to-face and may have been a good lip-reader but he could not follow ordinary conversation, especially in a crowd. When he got lost in the conversation, he tended to walk away and stare into the distance. references also present that his voice was weak and high-pitched [possibly suggesting a “deaf Speech” tone]. He had an independent personality, always liked being alone and loved being outdoors. Because of his hearing loss, Erastus was known as “Dif Smith.”

Life and Times in Mexican Texas (1821-1836)

In 1821, a total of about 3,500 settlers lived in the whole of the Mexican province of Tejas, concentrated mostly in San Antonio and La Bahia (now the city of Goliad, Texas) as settlers in the  frontier areas of these provinces were overwhelmingly outnumbered by indigenous people (Indians, mostly Commanche). Mexican Texas (1821-1836), as this period is known, was at first governed much like the old Spanish Texas but, as the new country developed, the 1824 Mexican constitution created a federal structure similar to the United States called United Mexican States. and the province of Tejas

frontier areas of these provinces were overwhelmingly outnumbered by indigenous people (Indians, mostly Commanche). Mexican Texas (1821-1836), as this period is known, was at first governed much like the old Spanish Texas but, as the new country developed, the 1824 Mexican constitution created a federal structure similar to the United States called United Mexican States. and the province of Tejas  was joined with the province of Coahuila to form the state of Coahuila y Tejas. To increase settler numbers, Mexico enacted the General Colonization Law in 1824, which enabled all heads of household, regardless of race, religion or immigrant status, to acquire land in Mexico. After a decade of political and cultural clashes between the Mexican government and the increasingly large population of American settlers in Texas the colonists became restless. The Mexican government had become increasingly centralized and the rights of its citizens had become increasingly curtailed, particularly regarding immigration from the United States. While colonists and Tejanos disagreed on whether their ultimate goals was independence or a return to the Mexican Constitution of 1824, the result of these discussions was the Texas Revolution.

was joined with the province of Coahuila to form the state of Coahuila y Tejas. To increase settler numbers, Mexico enacted the General Colonization Law in 1824, which enabled all heads of household, regardless of race, religion or immigrant status, to acquire land in Mexico. After a decade of political and cultural clashes between the Mexican government and the increasingly large population of American settlers in Texas the colonists became restless. The Mexican government had become increasingly centralized and the rights of its citizens had become increasingly curtailed, particularly regarding immigration from the United States. While colonists and Tejanos disagreed on whether their ultimate goals was independence or a return to the Mexican Constitution of 1824, the result of these discussions was the Texas Revolution.  The Texas Revolution (October 2, 1835 – April 21, 1836) was a rebellion of colonists from the United States and Tejanos (Texas Mexicans) who put up an armed resistance to the centralist government of Mexico. The uprising was actually part of a larger one that

The Texas Revolution (October 2, 1835 – April 21, 1836) was a rebellion of colonists from the United States and Tejanos (Texas Mexicans) who put up an armed resistance to the centralist government of Mexico. The uprising was actually part of a larger one that  included other provinces opposed to the regime of President Antonio López de Santa Anna, who believed the United States had instigated the Texas insurrection with the goal of annexation. This created chaos within the political convention of Texas revolutionary group attempting to establish a government but after some botched invasions, a second political convention in March 1836 finally declared independence and appointed leadership for the new Republic of Texas.

included other provinces opposed to the regime of President Antonio López de Santa Anna, who believed the United States had instigated the Texas insurrection with the goal of annexation. This created chaos within the political convention of Texas revolutionary group attempting to establish a government but after some botched invasions, a second political convention in March 1836 finally declared independence and appointed leadership for the new Republic of Texas.

Joining the Texas Army

Huston (1973 and Griffis (1958) indicate that during this time Deaf Smith spent much time away from his family as a surveyor and off in the wilderness on adventures. He enjoyed hunting, especially buffalo, and trained a dog to quietly warn him of danger. In 1825, Smith assisted in starting the development of land near Gonzales, Texas, that 400 families were going to colonize. Smith acted as a guide through the lands for the Texan colonists who began arriving in great numbers. At the outbreak of the Texas Revolution his loyalties were apparently divided but the Mexican central government and the Texan colonists both began

going to colonize. Smith acted as a guide through the lands for the Texan colonists who began arriving in great numbers. At the outbreak of the Texas Revolution his loyalties were apparently divided but the Mexican central government and the Texan colonists both began  to struggle for control. Deaf Smith with his feet in both cultures really avoided picking a side in the conflict. However, when he tried to ride home to evacuate his family from the danger of fighting, Mexican General Cos’s men tried to capture him, hitting him on the head with a saber and knocking off his hat as he was escaping. Huston (1973) found that he rode immediately to Army General Stephen Austin of the Texas Volunteers to offer his services as a scout and spy. He

to struggle for control. Deaf Smith with his feet in both cultures really avoided picking a side in the conflict. However, when he tried to ride home to evacuate his family from the danger of fighting, Mexican General Cos’s men tried to capture him, hitting him on the head with a saber and knocking off his hat as he was escaping. Huston (1973) found that he rode immediately to Army General Stephen Austin of the Texas Volunteers to offer his services as a scout and spy. He  had spent a lot of time learning the customs, manners, and language of the Mexican settlers and his knowledge of both the Hispanic and Anglo cultures within the Texas territory was very valuable to the new Army. Soon after joining the Texians, he became a revered scout, spy, and guide, a man of few words, but extremely loyal. Shortly thereafter he became the Army’s chief spy, and was known as “the eyes of the army” guiding Texian forces over the land and cultures he knew so well. He was a significant contributor to most of the battles of the revolution from the Beginning in Gozales to the final and deciding Battle of San Jacinto. Between 1835 and 1836, Smith rose to the status of a war hero, leading a group of recruits known as the New Orleans Greys. Historians report that at the Battle of Concepcion, he marched

had spent a lot of time learning the customs, manners, and language of the Mexican settlers and his knowledge of both the Hispanic and Anglo cultures within the Texas territory was very valuable to the new Army. Soon after joining the Texians, he became a revered scout, spy, and guide, a man of few words, but extremely loyal. Shortly thereafter he became the Army’s chief spy, and was known as “the eyes of the army” guiding Texian forces over the land and cultures he knew so well. He was a significant contributor to most of the battles of the revolution from the Beginning in Gozales to the final and deciding Battle of San Jacinto. Between 1835 and 1836, Smith rose to the status of a war hero, leading a group of recruits known as the New Orleans Greys. Historians report that at the Battle of Concepcion, he marched at the head of command into the city. There his excellent rifle skills, leadership and bravery helped the Texians force General Cos to retreat. He was again important in a skirmish known as the Grass Fight. After that, and a promotion, Captain Smith was the leader of General Sam Houston’s scouts and a sharpshooter instrumental in the surrender of General Cos when the Texans descended upon his old hometown, San Antonio de Bexar. At the Alamo, Smith served as a messenger for William B. Travis, who considered him “`the Bravest of the Brave’ in the cause of Texas.” Smith carried Travis’s letter from

at the head of command into the city. There his excellent rifle skills, leadership and bravery helped the Texians force General Cos to retreat. He was again important in a skirmish known as the Grass Fight. After that, and a promotion, Captain Smith was the leader of General Sam Houston’s scouts and a sharpshooter instrumental in the surrender of General Cos when the Texans descended upon his old hometown, San Antonio de Bexar. At the Alamo, Smith served as a messenger for William B. Travis, who considered him “`the Bravest of the Brave’ in the cause of Texas.” Smith carried Travis’s letter from  the Alamo on February 15, 1836. The brave Alamo defenders remained at their post, fighting for Texas Independence until the last, buying time for the young government to organize. Their memory fueled spirits on the Battlefield at San Jacinto and beyond inspiring courage in the face of patriotic sacrifice, “Remember the Alamo!”. General Houston was very upset by the fall of the Alamo to General Santa Anna and, March 13, he dispatched Captain Smith and Henry Karnes back to San Antonio to learn the status of the Alamo garrison. General Houston reported to his commander General Thomas Jefferson Rusk, “If living,” Smith will return with “the truth and all important news.” Captain Smith did return, bringing with him Mrs. Almeron (Susanna) Dickerson and her 15-month-old baby, Angelina. Mrs. Dickerson had been the only American woman at the Alamo.

the Alamo on February 15, 1836. The brave Alamo defenders remained at their post, fighting for Texas Independence until the last, buying time for the young government to organize. Their memory fueled spirits on the Battlefield at San Jacinto and beyond inspiring courage in the face of patriotic sacrifice, “Remember the Alamo!”. General Houston was very upset by the fall of the Alamo to General Santa Anna and, March 13, he dispatched Captain Smith and Henry Karnes back to San Antonio to learn the status of the Alamo garrison. General Houston reported to his commander General Thomas Jefferson Rusk, “If living,” Smith will return with “the truth and all important news.” Captain Smith did return, bringing with him Mrs. Almeron (Susanna) Dickerson and her 15-month-old baby, Angelina. Mrs. Dickerson had been the only American woman at the Alamo.

The Battle of San Jacinto

While the Alamo is decidedly more famous, the Battle of Jacinto was the one that decided the fate of both Texas and many other US states that were, at the time part of the United Mexican States.

While the Alamo is decidedly more famous, the Battle of Jacinto was the one that decided the fate of both Texas and many other US states that were, at the time part of the United Mexican States. According to the San Jacinto Museum, the Battle of San Jacinto expanded U.S. sovereignty and spread its culture to over a third of today’s contiguous states. After San Jacinto, Texas’ annexation in 1845 and the U.S. Mexican War, the United States would gain almost a million square miles of territory. As a direct result of the victory at San Jacinto, the United States would fulfill its “manifest destiny” of stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific. In addition to Texas, it gained New Mexico, Nevada, Arizona, California, Utah, and parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Kansas and Oklahoma. As a result of the Battle of San Jacinto, almost a third of what is now the United States of America changed ownership. It is one of the most decisive and consequential battles in the

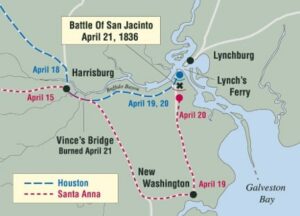

According to the San Jacinto Museum, the Battle of San Jacinto expanded U.S. sovereignty and spread its culture to over a third of today’s contiguous states. After San Jacinto, Texas’ annexation in 1845 and the U.S. Mexican War, the United States would gain almost a million square miles of territory. As a direct result of the victory at San Jacinto, the United States would fulfill its “manifest destiny” of stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific. In addition to Texas, it gained New Mexico, Nevada, Arizona, California, Utah, and parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Kansas and Oklahoma. As a result of the Battle of San Jacinto, almost a third of what is now the United States of America changed ownership. It is one of the most decisive and consequential battles in the  history of the United States and indeed the Western world. During the San Jacinto campaign Captain Smith captured a Mexican courier bearing important dispatches to Antonio López de Santa Anna, and on April 21, 1836, Smith and Houston requisitioned “one or more axes,” with which Houston ordered Smith to destroy Vince’s Bridge. Located on the most likely possible route of escape for Antonio López de Santa Anna and his column of the Mexican army, the burning of Vince’s Bridge helped prevent the Mexican soldiers from reaching the safety of nearby reinforcements. Its destruction by Texas armed forces, lead by Captain Erastus “Deaf” Smith who during the battle rode back and forth across the field behind the Texans waving his axe to let them know that the bridge was destroyed. He called to the fighters:

history of the United States and indeed the Western world. During the San Jacinto campaign Captain Smith captured a Mexican courier bearing important dispatches to Antonio López de Santa Anna, and on April 21, 1836, Smith and Houston requisitioned “one or more axes,” with which Houston ordered Smith to destroy Vince’s Bridge. Located on the most likely possible route of escape for Antonio López de Santa Anna and his column of the Mexican army, the burning of Vince’s Bridge helped prevent the Mexican soldiers from reaching the safety of nearby reinforcements. Its destruction by Texas armed forces, lead by Captain Erastus “Deaf” Smith who during the battle rode back and forth across the field behind the Texans waving his axe to let them know that the bridge was destroyed. He called to the fighters: “The bridge is down! They can’t get away! Victory or death!”

“The bridge is down! They can’t get away! Victory or death!”

According to historians, after the Battle of San Jacinto, Captain Smith acted as a scout and spy to monitor the retreat of the Mexican army. During that time, he learned of another planned attack and was able to stop it. After that, he resigned his commission and headed up a company of Texas Rangers monitoring a strip of land that both Mexicans and Texans  claimed. In February 1837, he and his Texas Rangers battled the Mexicans near Laredo and, although outnumbered, they suffered many less casualties. Smith’s goal was to “to raise the Texas flag of Independence on the spire of the Catholic Church at Laredo,” the rangers never made it to Laredo. Captain Erastus Deaf Smith left the Texas Rangers shortly after the battle and soon died at the age of 50 in his friend Randal Jones’s house in Richmond, Texas [now a suburb of Houston] likely of consumption, on November 30, 1837.

claimed. In February 1837, he and his Texas Rangers battled the Mexicans near Laredo and, although outnumbered, they suffered many less casualties. Smith’s goal was to “to raise the Texas flag of Independence on the spire of the Catholic Church at Laredo,” the rangers never made it to Laredo. Captain Erastus Deaf Smith left the Texas Rangers shortly after the battle and soon died at the age of 50 in his friend Randal Jones’s house in Richmond, Texas [now a suburb of Houston] likely of consumption, on November 30, 1837.

Captain Erastus “Deaf” Smith is so famous in Texas that in 1876 the state legislature named a county in the Texas panhandle Deaf Smith County, which was not organized until 1890, with the town of La Plata as the original county seat.

References:

Griffis, Faye Campbell. (1958). The Nine Lives of Deaf Smith. Dallas, Texas: Banks Upshaw and Company.

Huston, Cleburne. (1973). Deaf Smith, Incredible Texas Spy. Waco, Texas: Texian Press.

McNamara, Michael L. (2019). Personal Communication.

San Jacinto Museum (2019). The Battle/Birth of a Republic. Retrieved from the San Jacinto Museum, May 6, 2019.

Viets, Henry R. (1935). Some Features of the History of Medicine in Massachusetts during the Colonial Period, 1620-1770, Isis (1935), 23:389-405, retrieved May 4, 2019.