A few months ago at Hearing International we did a discussion of how you can hear plants grow.…. Strange things are now found among plants. It has been discovered that plants can actually tell if predators are after them bugs, animals and humans!

This is the story of how plants might hear, feel, smell or otherwise detect that they are being used as food and how they fend off these predators as well as warn their friends and relatives of this impending danger. Of course, these warnings have been going on since the beginning of time, but we are just finding out about how plants protect themselves from predators and the effects that this protection might have on humans: Could plants (our food) be sending and receiving auditory messages of impending danger?

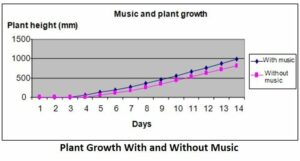

Many of us may have heard the ongoing idea that plants seem to prefer Classical Music over Rock n’ Roll. Is it possible that plants have a liking for Mozart and Beethoven rather than the Rolling Stones or Kiss? According to experts, there is evidence to suggest that plants thrive and are healthier when they are exposed to classical music on a regular basis in their growth environments. For instance, wine makers in Mantalcino, Italy play classical music for their grapevines, resulting in the production of better wine. In places where marijuana is legal, classical music is used to encourage healthier and larger plant growth. Some observations even indicate that plants tend to grow towards classical music and away from Rock n’ Roll.

While this idea might make sense based on anecdotal evidence, plant and animal physiologists typically do not investigate plants for consciousness or ESP, as their scientific understanding excludes the possibility of plants having emotions or perceptions at the human level. In simpler terms, plants lack ears, brains, or anything resembling anatomical auditory systems. To scientists, attributing plants with these capabilities would be as absurd as suggesting that bacteria or viruses possess brains and nervous systems.

Although the mechanisms behind plant communication have evolved over millions of years, the concrete evidence of plants warning each other about predators and having protective mechanisms is a relatively recent development, spanning just a few decades. This concept has gone from being a surprising discovery to facing skepticism and, ultimately, returning to the forefront of plant research due to meticulous and controlled scientific research.

Although the mechanisms behind plant communication have evolved over millions of years, the concrete evidence of plants warning each other about predators and having protective mechanisms is a relatively recent development, spanning just a few decades. This concept has gone from being a surprising discovery to facing skepticism and, ultimately, returning to the forefront of plant research due to meticulous and controlled scientific research.

In the Beginning…

The intriguing tale of this phenomenon begins with Cleve Backster, a former C.I.A. polygraph expert. In 1966, perhaps out of sheer boredom, Backster decided to connect a galvanometer to a dracaena houseplant’s leaf that he kept in his office.

To his amazement, he discovered that merely by envisioning the dracaena catching fire, he could make the polygraph machine’s needle register a spike in electrical activity, indicating that the plant was responding to stress.

This led to the question: “Could the plant be reading his mind?” Backster felt so astonished that he wanted to run out into the street and proclaim to the world, “Plants can think!”

This led to the question: “Could the plant be reading his mind?” Backster felt so astonished that he wanted to run out into the street and proclaim to the world, “Plants can think!”

In 1968, Backster published his initial findings, which received considerable skepticism from the scientific community. However, these findings garnered significant public attention, especially after they were featured in the bestseller “The Secret Life of Plants” by Peter Tomkins and Christopher Bird, published in 1973. Although the book faced criticism from scientists for promoting pseudoscientific claims, it documented controversial experiments that claimed to reveal unusual plant phenomena, including plant sentience. The book also discussed various philosophies and innovative farming methods inspired by these discoveries.

In the years immediately following the book’s publication, both amateurs and scientists attempted to replicate what became known as the ‘Backster effect.’ They sought to test the assertion that plants respond to human thoughts and, in particular, intentions to harm them.

And Later……..

Two studies published in 1983 demonstrated that willow trees, poplars and sugar maples can warn each other about insect attacks: Intact, undamaged trees near ones that are infested with hungry bugs begin pumping out bug-repelling chemicals to ward off attack. They somehow know what their neighbors are experiencing, and react to it. The shocking truth was that a brainless tree could send, receive and interpret messages of impending danger.

In 2013, McGowan discussed how early attempts to prove the concept of “talking trees” were met with criticism due to statistical flaws and artificial conditions, leading to a temporary halt in research on plant communication. However, recent scientific investigations have made a resurgence in the field.

Rigorous and carefully controlled experiments, conducted in various settings, have addressed these early criticisms, and it is now firmly established that when insects chew on leaves, plants respond by emitting volatile organic compounds into the air.

In 2011, Andrews highlighted a research project where scientists monitored when gypsy moth larvae first landed on a mature oak tree within a grove of oak trees. By analyzing the chemistry of the mature oak’s leaves, they discovered that the tree quickly produced a bitter tannin, making it an unappetizing choice for the larvae. Remarkably, all the other oak trees in the grove also altered the chemistry of their leaves, rendering them unattractive to the insects.

Recent studies have further confirmed that other plants can detect these airborne signals and adjust their production of defensive chemicals or mechanisms accordingly. The current debate no longer questions whether plants can sense one another’s biochemical messages; they can. Instead, it explores why and how they do this, with potential implications for improving crop resistance and intriguing questions about inter-organism knowledge sharing.

Plants Sharing Airborne Cues

To delve into this topic, it’s essential to clarify some vocabulary. Herbivores are creatures that primarily consume plants, while carnivores primarily eat meat. Omnivores, on the other hand, have diets that include both plants and meat. Richard Karban, an ecologist at the University of California, Davis, specializes in the communication of sagebrush plants.

According to Karban’s 2018 findings, when sagebrush is experimentally clipped, it releases volatile cues that trigger responses in undamaged branches on the same plant, different sagebrush plants, and even some other plant species. These cues induce various changes in neighboring plants, enhancing their defense against herbivores. However, the precise nature of these cues remains poorly understood.

According to Karban’s 2018 findings, when sagebrush is experimentally clipped, it releases volatile cues that trigger responses in undamaged branches on the same plant, different sagebrush plants, and even some other plant species. These cues induce various changes in neighboring plants, enhancing their defense against herbivores. However, the precise nature of these cues remains poorly understood.

Karban’s research suggests that airborne cues are involved, and methyl jasmonate is a potential signaling compound, although its role in natural settings is still unclear. He seeks to understand the costs and benefits of emitting and responding to these volatile cues. His research explores the multiple consequences of these cues, such as their effects on neighboring plants, nearby herbivores, as well as the predators and parasites of those herbivores. Additionally, Karban investigates the long-term fitness consequences for sagebrush resulting from their response to volatile cues.

Impact on Diet and Lectins

These ideas have led to the popularity of certain human diets promoted by physicians like Dr. Steven Gundry. His book is centered around the notion that some plants contain harmful substances known as Lectins.

Lectins are a type of protein that can attach to sugars and are sometimes referred to as “antinutrients” because they can hinder the body’s ability to absorb nutrients. Surprisingly, these antinutrients are present in foods that were previously considered healthy.

Lectins are believed to have evolved as a natural defense mechanism in plants, essentially acting as toxins to deter animals from consuming them. While they are lethal to bugs and other predators, some experts, including Gundry, argue that they can be harmful to humans. Foods such as beans, tomatoes, and other “nightshade vegetables” with thick skins are high in lectins and may pose dietary challenges for humans.

These lectins are the basis for popular diets like the Gluten-Free and Lectin-Free Diets.

Epilog:

The form of communication plants use for their interactions to fend off the predators is still a mystery. We now know that the idea of plant communication is not bunk, and their secretion of certain toxins and smells, and other warnings are real.

As for plants hearing? The jury is still out. While it is likely another type of signal but more research is necessary to facilitate a true answer.

References:

All Science Fair Projects (2016). Effect of music on plant growth. Retrieved January 15, 2019.

Andres, C. (2011). Are Trees Talking? Good Nature Travel. Retrieved January 15, 2019.

Cameron, D. (2018). Plants have a taste for classical music, but they especially detest rock ‘n roll. The Epoch Times. Retrieved January 13, 2019.

Gundry, S (2017). The Plant Paradox. New York: Harper Collins.

McGowan, K. (2013). The Secret Language of Plants. Quanta Magazine. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

Newitz, A. (2013). The growing evidence that plants can think and communicate. Gizmodo. iO9 we come from the future. Retrieved January 15, 2019.

Pollen, M. (2013). The intelligent plant. The New Yorker. Retrieved January 13, 2019.

Yong, E. (2019). Plants can hear animals using their flowers. The Atlantic, Science, Retrieved January 12, 2019.

About the author

Robert M. Traynor, Ed.D., is a hearing industry consultant, trainer, professor, conference speaker, practice manager and author. He has decades of experience teaching courses and training clinicians within the field of audiology with specific emphasis in hearing and tinnitus rehabilitation. He serves as Adjunct Faculty in Audiology at the University of Florida, University of Northern Colorado, University of Colorado and The University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

**this piece has been updated for clarity. It originally published on January 15, 2019

It has been known over a 100 years that plants have emotional responses. Dr. Bose, a scientist in India was the discoverer of plants reacting to loud speech, and negatively directed talk. Plant do seem to know their environment better than human beings.

To the previous commenter: can you give us a couple of references on that work?