A Towering Presence, On and Off the Diamond William Ellsworth “Dummy” Hoy overcame deafness at age 3 and societal stigma to enjoy a storied baseball career spanning 1886-1903. Playing centerfield for various major league teams, Hoy competed alongside future Hall of Famers capably.

His .287 batting average and mastery of small ball reflected exceptional physical talents.

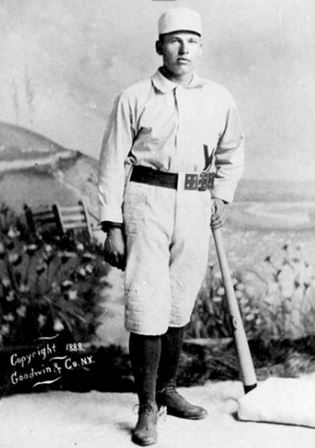

William Ellsworth “Dummy” Hoy (May 23, 1862 – December 15, 1961). Image credit, Wikipedia

However, Hoy’s greater legacy involved empowering those with disabilities and pioneering improvements benefiting teammates and players ever since. Credited by some with spurring umpires’ adoption of ball/strike/safe/out hand signals, Hoy maximized communication via clever methods like posting clubhouse instructions. And while clubs granted Hoy opportunities rarely afforded the Deaf in his era, Hoy earned respect through determination to excel – along with amassing 2,000+ hits.

Baseball Career

Back when Hoy was playing 1886-1902, nicknames were bluntly descriptive, often to the point of cruelty. To Hoy, his condition wasn’t an excuse; it was what it was. Indeed, he routinely referred to himself as “Dummy” and politely corrected those who, for whatever reason, called him “William or Bill.”

Hoy began his major league career in 1888 with Washington of the National League. A left-handed batter and right-handed thrower, he played center field with Buffalo, St. Louis, Cincinnati and Louisville. From the beginning of his career in Washington, he set out to communicate with his teammates.

He posted this statement on the clubhouse wall:

“Being totally deaf as you know and some of my teammates being unacquainted with my play, I think it is timely to bring about an understanding between myself, the left fielder, the shortstop and the second baseman and the right fielder. The main point is to avoid possible collisions with any of these four who surround me when in the field going for a fly ball. Whenever I take a fly ball I always yell ‘I’ll take it’–the same as I have been doing for many seasons, and of course the other fielders let me take it. Whenever you don’t hear me yell, it is understood I am not after the ball, and they govern themselves accordingly.”

Hoy’s yell was actually more of a squeak than a yell, but his teammates understood. Hoy played for Buffalo in the Players League in 1890, with St. Louis team in the American Association in 1891, then back to Washington in the National League in 1892 and 1893. He moved on to Cincinnati of the National League in 1894, where he stayed until going to Louisville of the National League in 1898 and 1899. He then played for Chicago of the American League in 1900 and 1901. He spent one more season with Cincinnati in 1902 and finally ended his baseball career with Los Angeles in the Pacific Coast League in 1903.

After retiring, Hoy worked for the government and became the longest-lived ex-MLB player ever at his passing in 1961 at 99. He referred to himself good-naturedly as “Dummy” in line with norms of his time. But Hoy was anything but in working around obstacles, exhibiting intelligence and even tutoring President Roosevelt’s son.

His Case for Cooperstown

Despite Hoy’s trailblazing career full of tribulations overcome, Baseball’s Hall of Fame has yet to grant his induction. However, momentum builds to recognize this 19th century standout as both hugely capable athlete and change agent who bettered baseball’s inclusiveness.

The precise origins of umpiring hand signals remain unclear, with some accounts predating Hoy’s prime years. However cy Rigler and Ed Dundon – the latter a deaf pitcher/umpire – also supposedly influenced signal development regionally. In any case, Hoy’s presence increased awareness. And starting in the minors before Majors, umpires’ gestures surely aided Hoy’s comprehension amid rising stadium clamor as the game modernized.

Some scholars argue Hoy’s Cooperstown enshrinement would appropriately honor overachievers and normalize disabilities, aligning with American ideals. Fans can support the cause by signing petitions under review by the Hall committee currently.

For opening doors to diverse big leaguers and spurring helpful innovations, Hoy’s spirit merits recognition.

About the author

Robert M. Traynor, Ed.D., is a hearing industry consultant, trainer, professor, conference speaker, practice manager and author. He has decades of experience teaching courses and training clinicians within the field of audiology with specific emphasis in hearing and tinnitus rehabilitation. He serves as Adjunct Faculty in Audiology at the University of Florida, University of Northern Colorado, University of Colorado and The University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

**this piece has been updated for clarity. It originally published on September 16, 2014