“This is the story of how we begin to remember

This is the powerful pulsing of love in the vein

After the dream of falling and calling your name out

These are the roots of rhythm

and the roots of rhythm remain.”

Paul Simon – “Under African Skies”

By H. Christopher Schweitzer, Ph.D.

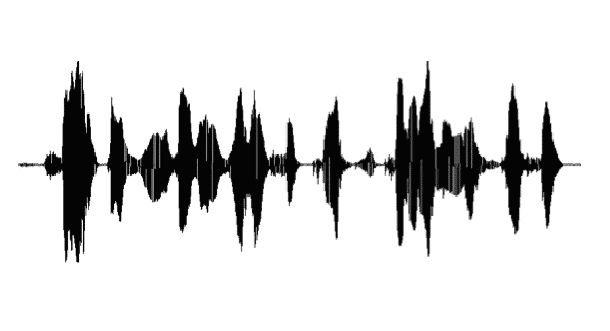

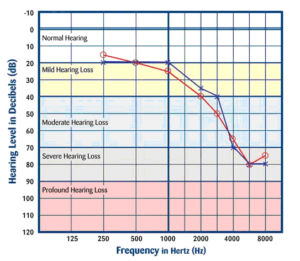

In a previous blog, I had lamented how most audiometric assessments are two-dimensional, commonly devoid of the crucial dimension of Time. It’s a topic that merits further elaboration and one of enduring interest{{1}}[[1]]Schweitzer, H.C. (1986) Time: the third dimension of hearing aid performance, Hear. Instr. 37(1).[[1]], but one that’s understandable as a natural consequence of the way we read and portray data, audiological or other. It’s naturally rather difficult to portray the time-varying property of the essence of what every hearing care client most commonly seeks … spoken messages. But when we do draw time into those two dimensions, as in the sample below, we know to move our eyes from left to right in a rude attempt to place time on the horizontal.

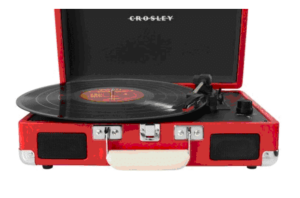

But hearing professionals work in the world of sound, and it is movement, change over time that brings sound to life. It was the movement of the platter that allowed the needle on an Elvis Presley vinyl record to carry his hip-swaying canticles to baby boomers, or Enrico Caruso’s evocative embrace to their parents’ gramophone.

The needle on a stationary recording disc is not unlike the static content of the standard audiogram – it’s temporally frozen.

Of course it’s useful, but unquestionably limited to the two dimensions of intensity and frequency. It could be said that this aspect of audiometry is sine tempore – frozen signs, unchanging in time. The needle is on the record, but there is no movement.

Consider also the physicality of spoken language. We know speech to be a stream of rhythmic beats of the body pushing air through its muscular sound board, from diaphragm to highly trained neck and head articulators, like fingers on a flute. Paul Simon’s heavy-beat chorus recalled at the top of this blog is a compelling reminder of the “roots” of spoken language – the mistily-blanketed target of most hearing rehabilitation efforts. Before pure tones, fricatives, consonants, and probably even rapid second-formant transitions, we almost certainly heard the rhythm of our mother’s voice in utero.

Those thumping syllabic pulses, delivered via fluid acoustics, set the oto-neurological stage for our home language acquisition, and they are most likely the first elements of acquiring a second, or new, language. At least that what a fairly large body of linguistic science and fetal audition suggest. {{2}}[[2]]Gerhardt KJ, Abrams RM (2009). Fetal exposures to sound and vibroacoustic stimulation. J Perinatology 20:S21-30.[[2]] {{3}}[[3]]Graven, SN and Browne JV (2008). Auditory development in the foetus and infant. Newborn and Infant Nursing Reviews.[[3]] {{4}}[[4]]Fridman R (2000) The maternal womb: the first musical school for the baby. Journal of Pre-natal and Peri-natal Psychology and Health 15 (1) Fall 2000[[4]] {{5}}[[5]]Skehan, Peter (1998) A Cognitive Approach to Language Learning. Oxford University Press.[[5]]

The “root’s of rhythm,” it would seem, are also the roots of spoken language, according to many scholars.

Adam Tierney and Nina Krause’s recently reported work from Northwestern University on the connection between beat detection and body rhythmic skills speaks wonderfully to this topic. Additionally, David Poeppel from NYU’s Psychology Department has collected extensive data indicating that the rhythmic patterns of speech are tuned to the brain’s natural oscillatory patterns, suggesting that speech seems to exploit the brain’s pre-existing rhythmic-processing architecture{{6}}[[6]]Giraud, A, & Poeppel D. (2012) Cortical oscillations and speech processing: emerging computational principles and operations. Nature Neuroscience. 15, 511-517, published on line 18 March 2012[[6]]. Published in the September 18 issue of The Journal of Neuroscience, Tierney and Krause’s work gives well-controlled evidence that people who are better able to move to a beat show more consistent brain responses to speech than those with less rhythm. Besides suggesting that musical training may improve the brain’s management of language it points toward the importance of synchronization of movement and hearing! The work shines a well-focused light on this previously murky relation. Click here for a summary of the article from the Society for Neurosciences.

The Rhythm of Language

Prowess in beat perception seems to be a robust and important aspect of auditory memory for non-musicians, as well. This is discussed at length in Daniel Levitin’s book{{7}}[[7]]Levitin, D. (2006). This Is Your Brain on Music. Penguin Books. London[[7]] on neuro-acoustics. “Rhythm stirs our bodies. The coming together of rhythm and melody bridges our cerebellum (the motor control center),” he writes. He goes on at length to describe how well-developed our neural equipment is for capturing and tuning in to the rhythmic properties of sound.

Returning to the work of rehabilitative hearing professionals, if the goal of the pursuit is (obviously) to reduce the burdens of spoken message reception, it seems that measures of prosody perception should be considered. The rhythm of our native language is apparently learned in the first months of life (Skehan, P., 1998; Fridman, R., 2000) and is considered important enough that an entire “R-Hypotheses” has been proposed{{8}}[[8]]Nazzi T, Bertoncini J, Mehler, J. (1998) Language discrimination by newborns: Towards an understanding of the role of rhythm. J Exp Psych: Human Perception & Performance. 24 (3) 757-766.[[8]], the “R,” of course, representing rhythm. In other words, it is not a secondary or tertiary aspect of hearing speech, but the groundwork upon which the cortical central processor is in constant surveillance.

Most non-native speakers are far better at developing reading comprehension than speaking without obvious accents. English is considered a “stress-timed” language and the basic unit is the beat patterns of syllables, some of which are stressed for emphasis and sprinkled over multi-syllabic words, sentences and phrases. In contrast, French, Turkish, and West Indian English are considered “syllable-timed” languages the stress is not an important element. Hence, although the ESL speaker may use all the correct words, they do not “sound” right to those who learned their English rhythms beginning in pre-natal listening mode. For languages with similar rhythm, intonation apparently becomes an important differentiator. For the already hearing-compromised listener, the altered flow pattern of non-natural prosody very likely imposes a further layer of signal degradation.

To conclude, it seems that there is ample evidence to affirm the proposition of the Cuban-American philosopher Gloria Estefan – “… the rhythm is gonna get you.” Enlarging our recognition of the contribution of prosody perception in our approaches to assist people who struggle to hear and understand spoken messages is overdue. Perhaps, the profession’s long affiliation with speech and language sciences could benefit from new touch points with mutually beneficial outcomes. For all our well-developed measures of thresholds for various sinusoids and unnaturally constructed, but well-controlled, spondee words, it seems relevant to remember that first there was rhythm. Excuse me, I have to get up and dance.

_

H. Christopher Schweitzer, Ph.D., is a regular contributor to HHTM. Dr. Schweitzer is the Director of HEAR 4-U International; Chief of Auditory Sciences at Able Planet, Inc.; and Senior Audiologist, Family Hearing Centers in Colorado.

Chris- I would very much appreciate a copy of your 1986 paper ( The third dimension…).

Thank you Harry Teder