Hearing Aid Price is still in the closet, but it’s being outed by professional and public outcry by squeezed Audiologists and consumers.{{1}}[[1]]I don’t know if hearing aid dispensers are feeling squeezed too, but probably.[[1]] If those two groups are outside picketing, who’s in the closet? Current conventional wisdom points to Machiavellian Manufacturing Monopolists. Before we jump on that bandwagon, let’s take a peek in the closet for verification.

True or False: The hearing aid industry uses every new thing to raise prices.

Maybe True, maybe False. Post #1 in this series established two illustrated “facts”:

- Hearing aid Price is Rising, as measured by actual retail dollars spent. We know that from a diverse series of unscientific{{2}}[[2]]This is not a term of aspersion. It is the statistician’s word for surveys administered without a random sample, among other things.[[2]]surveys of consumers (MarkeTrak) and retailers (Hearing Review, Hearing Journal).

- Hearing Aid Price is Not Rising, if you adjust dollars spent by the rate of inflation.

Well, rats. That’s not helpful unless you belong to a special interest group that benefits from believing that Prices are Rising (e.g., consumers) or one that benefits from the notion that Prices are Stable (e.g., manufacturers). “Lies, damned lies, and statistics” comes to mind, prompting us to excavate a bit deeper in the Price Closet.

But First, More Economic Stuff (you know you want it)

- Nominal dollars. Also called “actual currency,” not adjusted for inflation over time. These are dollars you have in your pocket RIGHT NOW, valued at what they will buy you RIGHT NOW.

- Consumer Price Index.{{3}}[[3]] The CPI does not include government purchases and investment goods and is the most widely used price index for consumer spending.[[3]]Usually called the CPI, this is an inflation index published monthly by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The CPI shows the percentage change in the price of a defined market basket of goods and services over time from a base period. If the CPI goes up, the value of a dollar down, so it takes MORE nominal dollars to buy the same thing.

- Real dollars. Also called “constant or relative dollars,” these are nominal dollars in a time series that are adjusted for inflation (“deflated”) by multiplying/dividing them by the CPI or some other price index. The adjusted time series in real dollars allows us to see whether there is actual growth or just inflation effects. To say that the relative price of hearing aids has risen/fallen in recent years is to say that their price relative to other defined goods and services (e.g., computers, medical services)—has increased or declined. Note that the real Price of hearing aids can decrease even when nominal Price increases.

- Purchasing Power links all of the above by converting currency to real dollars indexed to a specified year. Purchasing Power increases when CPI goes down; it decreases when CPI goes up. It gives you a general feel for the change in the value of $1 today versus previous years: 4 cups of coffee in the 1960s, not even 1 cup today. We can use a Purchasing Power Calculator to answer our Pricing question: “How have out of pocket resources spent on hearing aids changed over time for those in our market?”

The “Real” Price of Hearing Aids

Last time, I went over a good article in Hearing Review by Jay McSpaden that showed relatively constant Price for linear, non-programmable hearing aids from 1980 to 2005 (Fig 2, previous post).

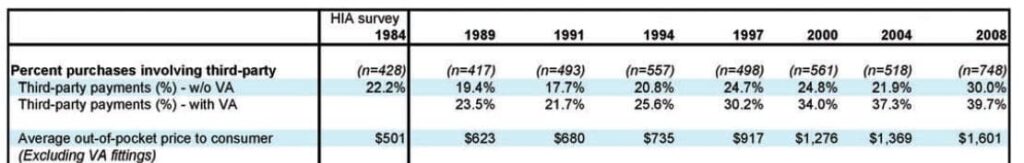

If we want to look at all types of hearing aids over a similar period, we can start with the MarkeTrak data of 7 surveys from 1989 to 2008, shown in Figure 1 and Table 1. Response validity is an issue — 17% of consumers thought Medicare helped out with the cost of their hearing aids. The data include 3rd party payments and discounts, so MarkeTrak numbers may be slightly low. On the other hand, the data rely on consumers’ memories/estimates of what they paid. To the extent that consumers tend to estimate or round up, MarkeTrak numbers could be slightly high. Whatever… these are real numbers so let’s use them.

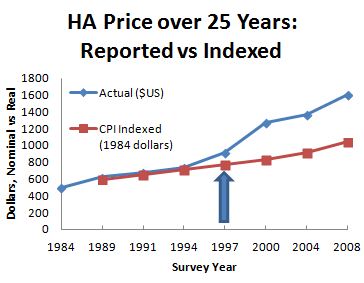

Figure 2 is what happens when the Marketrak nominal dollars are indexed to the 1984 average cost of hearing aids, as reported by HIA. That analyses shows that the reported average price of all

types of hearing aids increased at the same rate as inflation until 1994, after which hearing aid prices began to rise, then shot up in 1997, substantially outpacing inflation in succeeding years. In other words, it cost MORE to buy a hearing aid, on average, after 1994 than it did in previous years surveyed.

Paradoxically, Price may not have risen. The real dollar value hinges on the assumption that everything in the “defined basket of goods” stays the same, meaning that the comparison assumes hearing aids are the same as those sold in 1984. McSpaden has already shown us that those hearing aids (linear, non-programmable) did not increase in Price (1980$), which makes sense because they were largely an undifferentiated product in the decades before the 90s.

It’s no coincidence that 1994 and 1997 mark points of departure from 1984 indexed dollars — respectively, those years marked the advent of CICs and the first full year of digital hearing aid production in the US market. Those are game changers that we’ll revisit in the next post.

(editor’s note: this is Part 2 in the multi-year Hearing Aid Pricing series. Click here for Part 1 or Part 3)

photo courtesy of agnosticpk

Holly,

Looking forward to your next post. Clearly, analog is not even a comparison to modern digital hearing aids… That being said, the rising price differential based on indexed CPI is very interesting indeed. I’m curious how that graph looks up to 2013…

Hi AuD. Hope the next post was in line with your expectations and satisfaction. We’ll have to wait awhile to fill out the 2013 data points.

Hi Holly,

Interesting article. Another way of looking at hearing aid prices is to compare them to similar things.

Hearing aids are the only electronic gadgets I know of whose prices have gone up. Computers, TVs, mobile phones are all examples where price has gone down and functionality has increased, in some cases enormously.

Take laptops. Maybe ten years ago, they cost typically $3000 and weighed 9 pounds (4 Kg). Now, they cost typically $700, weigh 3 pounds, run much faster, have much nicer graphics and are easier to use.

There are three big differences between hearing aids and other electronic gadgets that help to explain the price behavior. The first is production volumes. Chips are made in the millions; computers and TVs have production runs of hundreds of thousands. While I have no numbers, I imagine hearing aid production runs are in the low tens of thousands at most. The second is the cost of research and product development. These are obviously very high for hearing aids, though I don’t have figures to hand, and must be recovered from the small production volumes. The third is that, as someone once said, most computers aren’t delivered; they’re abandoned. But hearing aids require careful adjustment and fitting by skilled people, and that costs.

However, it’s difficult to imagine that those factors can account for the whole difference in price behavior. I’m left with the same suspicion as yourself: someone, somewhere, is doing very nicely thank you.

Delayed greetings, Bruce, and thanks for your comment. I hope the next post in this series was an acceptable response to your observation that hearing aids can be compared to similar electronic things. That post concludes as follows: “Those of you who have mentioned falling prices in consumer electronics as a contrast to price growth in the hearing aid industry can take comfort that we will become more like other consumer industries as our market becomes more Price elastic.”