by Kate Baldocchi, AuD & Amyn M. Amlani, PhD

The hearing aid industry has experienced remarkable technological advancements in signal processing capabilities over the past two decades. During this same time, the profession of audiology has increased its efforts to act on the needs of consumers (e.g., patient-centered care), have systems in place (e.g., evidenced-based practice [EBP]), and follow them rigorously.

Yet, at the conclusion of each business year, the industry repeatedly asks the same question:

Why is hearing aid adoption/uptake essentially unchanged?

Chronic topics of discussion centered around this question include:

- Less-than-ideal hearing aid adoption rates globally, including government subsidized devices1

- Impact of Big Box and forward integration business models

- Upcoming introduction of over-the-counter hearing aids

- Deficit and high attrition rate of hearing health providers, and

- Declining renumeration for professional services and patient accessibility.

The factors affecting the present state of hearing health are hallmarks of a wicked, or ill-structured problem.

What is a Wicked Problem?

In their 1973 publication, Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning, Rittel and Webber2 introduce the concept of a wicked problem. These authors classified wicked problems as unique problems that are a symptom of other problems, lacking a stopping rule, and involving stakeholders with varying descriptions of the problem. Camillus (2008) wrote,

“Wicked problems often crop up when organizations have to face constant change or unprecedented challenges. They occur in a social context; the greater the disagreement among stakeholders, the more wicked the problem. In fact, it’s the social complexity of wicked problems as much as their technical difficulties that make them tough to manage. Not all problems are wicked; confusion, discord, and lack of progress are telltale signs that an issue might be wicked.”

Hearing healthcare is being forced to evolve through its own series of wicked problems. What does our professional future hold? What is our plan?

The industry and profession have approached problem-solving mainly using Evidence Based Practice (EBP). EBP provides solutions to linear and tame problems such as, “how to measure hearing thresholds,” “how to measure hearing aid output,” and “what are the symptoms of Meniere’s disease?”

Hearing healthcare relies on EBP to ensure viability and reliability of best practices. It is crucial for quality of care consistency and it is our moral and ethical responsibility to implement on behalf of the consumers we serve and treat. However, EBP’s linear approach to problem-solving, coupled with a time delay of 17 years between research realization and clinical implementation, fails to encourage divergent thinking, creativity, agility, and collaboration that fosters “future-focused” innovation.

To Improve our Future…

We must start with the altering our mindset. To evolve as an industry and profession, we should begin our pivot by becoming aware of our individual “biases and behaviors that hamper innovation.”

As an example, take a look at the Rubin’s Vase below.

What do you see?

-A single vase?

-Two profiles facing one another?

-Both?

This visual exercise affords the eyes and mind to shift when focusing between the figure (i.e., signal) and ground (i.e., noise). As such, an increase in dialogue emerges such as:

-How does the switch feel to you?

-What is the “signal”? What is the “noise”?

-How do you know?

This exercise is best summarized by vuja de.

“No matter how it is accomplished, the vuja de mentality is the ability to keep shifting opinion and perception. It means shifting our focus from objects or patterns that are in the foreground to those in the background, between what psychologists call “figure” versus “ground.” It means thinking of things that are usually assumed to be negative as positive and vice versa. It can mean reversing assumptions about cause and effect, or what matters most versus least. It means not traveling through life on automatic pilot.” (Robert Sutton, 2002)3

Applying the vuja de Mindset

When applying the vuja de (i.e., “already seen it”) perspective to hearing healthcare, one must recognize the presence of social challenges. This, then, lends itself to the use of a different lens to seek social methodologies for solutions, such as the design process (i.e., a plan for the implementation of an activity or process).

History of Design Process

Design disciplines shape what individuals see (e.g., fashion, graphic, interior design), the items they engage with (e.g., product, software design), and how they interact with people and institutions (i.e., systems design).

There are two basic and fundamentally different ways to define the process of design:4

- the rational model, and

- action-centric model.

The rational model is a structured approach with a foundation in research, one that resonates with an analytical, scientific mindset.4

The action-centric model, true to its nature, is based in an empiricist philosophy.5 This model’s foundation of creativity, emotion, and improvisation allows for flexibility when adapting to evolving challenges. The action-centric model embraces the abstract and resonates with an intuitive, artistic mindset.

Design Thinking

The Hasso-Plattner Institute of Design at Stanford (d.school), founded by IDEO founder David Kelley, teaches design thinking to engineering and business students. The d.school design thinking methodology synthesizes the rational model and action-centric processes of design. (Note there are many approaches to design thinking: if you’ve seen one methodology to design thinking, you’ve seen one methodology to design thinking.)

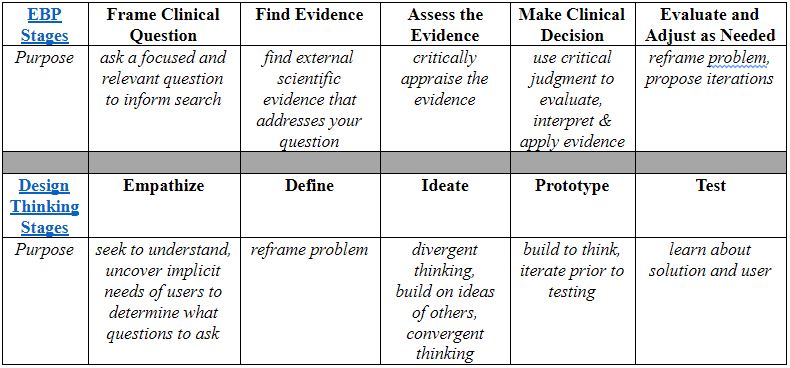

The d.school is regarded as a thought leader in design thinking, and their methodology consists of a nonlinear five-stage process, seen in the Figure 2 below.

For comparison, we have tabulated the linear processes of EBP in Table 1.

Design thinking methodologies vary in structure, such as the procedural-based Google Ventures Design Sprints or the spontaneous and informal-based Tiny Designs practiced throughout IBM’s ecosystem.

Design Thinking Applications in Hearing Healthcare

To date, we are aware of several applications of design thinking in hearing healthcare. In 2007, Oticon embraced the design thinking model and employed a team that attempted to re-think the supply-side of hearing aid acquisition, including service provision and product development. In 2010, this team was dissolved.

In 2011, Unitron employed design thinking concepts in the application of its Moxi product, which included placing the potential user at the core of new product development. This approach has not only refined the product, but also the features and their applications, aesthetics, and comfort.

The Department of Veterans Affairs successfully implemented design thinking by providing tools (the VA Center for Innovation’s Human-Centered Design Toolkit) and programs (Veterans Experience Office) to improve the healthcare needs of our Veterans.

Lastly, the Ida Institute utilizes design thinking in its approach of hearing care by ensuring that providers utilize a patient-centered care model that respects the preferences, values, decisions, and goals of the impaired listener.

Summary

We believe that for audiology to remain relevant in the future of hearing healthcare, there is a critical need to assess new ways of assessing the challenges faced by the industry and profession.

Design thinking offers an innovative methodology at assessing the industry and profession through the proverbial lens, with an opportunity to gauge ourselves from a different vantage point. This view could potentially allow for a new solution(s), through social context, to reduce barriers, improve access, while serving patients with impaired hearing with the best possible care.

In future installments of HHTM, we will enlighten readers with the various tenets of design thinking, along with their potential impact on patient accessibility and affordability, the latent reduction in provider resources, and the increase in trust and shared decision-making in treatment protocols that yield increased uptake of hearing healthcare services and technologies.

References

- Valente M, Amlani AM. (2017). Cost is not the primary reason why patients do not seek hearing aids. Journal of American Medical Association Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, 143(7), 647-648. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2017.0245.

- Rittel HWJ, Webber MM. (1973). Dilemmas in general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2): 155-169.

- Sutton RI. (2002) Weird Ideas That Work. 11½ Practices for Promoting, Managing, and Sustaining Innovation. Free Press: New York, New York.

- Dorst, K. Dijkhuis J. (1995). Comparing paradigms for describing design activity. Design Studies, 16(2): 261-274.

- Simon HA (1996). The Sciences of the Artificial. MIT Press: Cambridge, MA.

About the Authors

Kate Baldocchi, AuD, is an audiologist with Lucid Hearing and a member of the Austin, Texas, chapter of the Hearing Loss Association of America. Dr. Baldocchi is a proponent of human-centered design in hearing healthcare, who envisions design as a vehicle for innovation that can help improve the lives of impaired listeners and the approaches providers utilize in service provision.

Amyn M. Amlani, PhD, is the Director of New Practice Development at Audigy, a data-driven, management group for audiology and hearing care, ENT group, and allergy practices in the United States. Prior to this position, Dr. Amlani was an academician for nearly two decades. He also serves as section editor of Economics for Hearing Health Technology Matters.