Neuilly-sur-Seine is a French commune just west of Paris, in the department of Hauts-de-Seine. A suburb of Paris, Neuilly is immediately adjacent to the city and is composed of mostly wealthy,  select residential neighborhoods. For centuries it has been the wealthiest and most expensive suburb of Paris, often recognized as one of the safest and

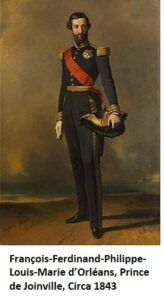

select residential neighborhoods. For centuries it has been the wealthiest and most expensive suburb of Paris, often recognized as one of the safest and  most child-friendly of all Parisian suburbs. Here, to Louis Philippe, Duke of Orléans and his wife Marie Amalie of Bourbon-Sicilies their third son François-Ferdinand-Philippe-Louis-Marie d’Orléans, Prince de Joinville was born August, 14, 1818. Although the order of succession for French Kings is rather complicated, the two royal families of France were the Bourbons and Orléans. From 1709 until the French Revolution, the Orléans Dukes were next in the order of succession to the French throne after members of the senior branch of the House of Bourbon, descended from king Louis XIV. French history for monarchs, dictators such as Napoleon, and their constitutional Monarchy is a bit complicated but basically François‘s father, Louis Philippe, was the “King of the French” from

most child-friendly of all Parisian suburbs. Here, to Louis Philippe, Duke of Orléans and his wife Marie Amalie of Bourbon-Sicilies their third son François-Ferdinand-Philippe-Louis-Marie d’Orléans, Prince de Joinville was born August, 14, 1818. Although the order of succession for French Kings is rather complicated, the two royal families of France were the Bourbons and Orléans. From 1709 until the French Revolution, the Orléans Dukes were next in the order of succession to the French throne after members of the senior branch of the House of Bourbon, descended from king Louis XIV. French history for monarchs, dictators such as Napoleon, and their constitutional Monarchy is a bit complicated but basically François‘s father, Louis Philippe, was the “King of the French” from  1830-1848 as a Constitutional Monarch. Even if the monarchy was still in place François , an Orléans Prince, being the third son would have put him quite distant from becoming King. Young François trained for Naval service and was commissioned a Lieutenant in the French Navy in 1836. His first conspicuous and outstanding service was at the Bombardment of San Juan de Ulua (Veracruz), in November 1838. Commanding the ship Créole, he headed a landing party and took the Mexican general Mariano Arista prisoner with his own hand at Veracruz battle endearing him to his superiors.

1830-1848 as a Constitutional Monarch. Even if the monarchy was still in place François , an Orléans Prince, being the third son would have put him quite distant from becoming King. Young François trained for Naval service and was commissioned a Lieutenant in the French Navy in 1836. His first conspicuous and outstanding service was at the Bombardment of San Juan de Ulua (Veracruz), in November 1838. Commanding the ship Créole, he headed a landing party and took the Mexican general Mariano Arista prisoner with his own hand at Veracruz battle endearing him to his superiors.

The Deafness

In his 20s (a pproximately 1838 or so), the Prince began to lose his hearing and over time it began to cause problems for him in communication. While it is sheer speculation and there could many other causes, due to the intermarriage among the 19th century royal families of Europe, otosclerosis was rampant throughout the royalty. In an effort to maintain the sense of hearing so essential to becoming an French Navy Admiral, he endured a most painful, yet failed, surgery said to “involve the boring of several holes in his skull and ears”. French physicians and surgeons had an early interest in curing deafness, probably due to the Paris School that was a seat of deaf education at the time. Drilling holes in the head for deafness was a practice conducted in the early to mid 19th century, but there is not much information as to the Prince’s specific surgical treatment, the surgeon that performed the procedure or where it was conducted.

pproximately 1838 or so), the Prince began to lose his hearing and over time it began to cause problems for him in communication. While it is sheer speculation and there could many other causes, due to the intermarriage among the 19th century royal families of Europe, otosclerosis was rampant throughout the royalty. In an effort to maintain the sense of hearing so essential to becoming an French Navy Admiral, he endured a most painful, yet failed, surgery said to “involve the boring of several holes in his skull and ears”. French physicians and surgeons had an early interest in curing deafness, probably due to the Paris School that was a seat of deaf education at the time. Drilling holes in the head for deafness was a practice conducted in the early to mid 19th century, but there is not much information as to the Prince’s specific surgical treatment, the surgeon that performed the procedure or where it was conducted.

After his military success at Veracruz, the prince of the realm was awarded the Cross of the Legion of Honor and promoted to Captain and, in 1840, was entrusted with bringing the remains of Napoleon from Saint Helena to France. Being excluded from continuing a career in the Second Empire’s navy, in 1851, he announced his candidacy for the French presidential electi on to be held in 1852, hoping to pave the way for an eventual restoration of the monarchy. The attempt to become a second “Prince-President” was aborted by 2 December 1851 coup by which the first Prince-President, Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, effected his own ascension to the throne. When Napoleon III assumed the throne, the French people turned against the ruling House of Orléans. As a result, the Prince was exiled, and eventually made England his home during this time.

on to be held in 1852, hoping to pave the way for an eventual restoration of the monarchy. The attempt to become a second “Prince-President” was aborted by 2 December 1851 coup by which the first Prince-President, Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, effected his own ascension to the throne. When Napoleon III assumed the throne, the French people turned against the ruling House of Orléans. As a result, the Prince was exiled, and eventually made England his home during this time.

American Civil War Service

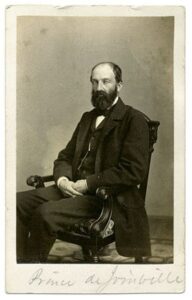

According to Lang (2017), in September 1861, the exiled Prince offered his services to President Lincoln, whom he praised for repressing the rebellion (The American Civil War). In the Prince’s 1862 book, The Army of the Potomac: Its Organization, Its Commander, and Its Campaign, he presented Lincoln presented as a President that was protecting the rights that, until then, “had made the American people the happiest and freest people of the earth.” The photo to the left a the Prince in America in 1862. Lincoln’s Assistant Private Secretary John Hay described the Prince as having the finest mind he ever met in the army. In October, Lincoln appointed him and his two nephews, also exiled

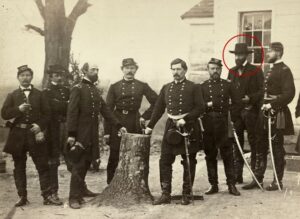

According to Lang (2017), in September 1861, the exiled Prince offered his services to President Lincoln, whom he praised for repressing the rebellion (The American Civil War). In the Prince’s 1862 book, The Army of the Potomac: Its Organization, Its Commander, and Its Campaign, he presented Lincoln presented as a President that was protecting the rights that, until then, “had made the American people the happiest and freest people of the earth.” The photo to the left a the Prince in America in 1862. Lincoln’s Assistant Private Secretary John Hay described the Prince as having the finest mind he ever met in the army. In October, Lincoln appointed him and his two nephews, also exiled  Princes, to the staff of Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, the “Young Napoleon,” who had replaced the venerable Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott as commander-in-chief of the Union armies. From the outset, McClellan considered Prince de Joinville a noble character

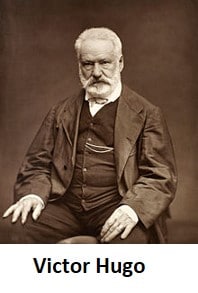

Princes, to the staff of Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, the “Young Napoleon,” who had replaced the venerable Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott as commander-in-chief of the Union armies. From the outset, McClellan considered Prince de Joinville a noble character . “His deafness was, of course, a disadvantage to him, but his admirable qualities were so marked that I became warmly attached to him.” In the 1862 photo at left, Prince de Joinville is in civilian clothes and to his right is his nephew, Prince Philippe of Orléans, Count of Paris also serving on McClellan’s staff. Speaking of the Prince de Joinville, McClellan wrote to his wife, “He bears adversity so well & so uncomplainingly. I admire him more than almost any one I have ever met with—he is true as steel—like all deaf men very reflective—says but little & that always to the point.” Fourteen years before the Prince served in the American Civil War, French writer Victor Hugo reminisced about his friend’s deafness, one day he said to me, “Speak louder, I am deaf as a post”. Hugo further remembered the Prince as a prankster and regarding his deafness, “Sometimes it saddens him, sometimes he makes light of it … Since he cannot talk as he wants to, he keeps his thoughts to himself, and this sours him.” Prince de Joinville was also talented artist and vividly captured the experiences of American soldiers in more than 50 watercolors and sketches, recording the beauty of the

. “His deafness was, of course, a disadvantage to him, but his admirable qualities were so marked that I became warmly attached to him.” In the 1862 photo at left, Prince de Joinville is in civilian clothes and to his right is his nephew, Prince Philippe of Orléans, Count of Paris also serving on McClellan’s staff. Speaking of the Prince de Joinville, McClellan wrote to his wife, “He bears adversity so well & so uncomplainingly. I admire him more than almost any one I have ever met with—he is true as steel—like all deaf men very reflective—says but little & that always to the point.” Fourteen years before the Prince served in the American Civil War, French writer Victor Hugo reminisced about his friend’s deafness, one day he said to me, “Speak louder, I am deaf as a post”. Hugo further remembered the Prince as a prankster and regarding his deafness, “Sometimes it saddens him, sometimes he makes light of it … Since he cannot talk as he wants to, he keeps his thoughts to himself, and this sours him.” Prince de Joinville was also talented artist and vividly captured the experiences of American soldiers in more than 50 watercolors and sketches, recording the beauty of the  changing landscapes and the ugliness of war. As the Prince once remarked, “Everybody writes his memoirs. I have drawn mine.” Prince de Joinville’s watercolor and other sketches were highly realistic, and many of his military sketches were later published in A Civil War Album of Paintings. Toward the end of the Peninsula Campaign (June 1862), difficulties between France and the U.S.A. over Mexico caused the prince to withdraw from the Union forces, and he returned to Europe.

changing landscapes and the ugliness of war. As the Prince once remarked, “Everybody writes his memoirs. I have drawn mine.” Prince de Joinville’s watercolor and other sketches were highly realistic, and many of his military sketches were later published in A Civil War Album of Paintings. Toward the end of the Peninsula Campaign (June 1862), difficulties between France and the U.S.A. over Mexico caused the prince to withdraw from the Union forces, and he returned to Europe.

After his American service, he was little heard of until the overthrow of the Second French Empire in 1870, when he re-entered France, only to be promptly expelled by the government of national defense. Returning incognito, he joined the army of General Louis d’Aurelle de Paladines, under the assumed name of “Colonel Lutherod” and fought bravely to overthrow the Second French Empire. Afterwards, divulging his identity, formally sought permission to continue to serve. Gambetta, however, arrested him and sent him back to England. In the National Assembly elected in February 1871, however the prince was restored by two départements and elected to sit for the Haute-Marne. By an arrangement with Adolphe Thiers, however, the prince did not take his seat until Theirs had been elected president of the provisional French republic. His deafness prevented him from making any contribution in the Assembly, and he resigned his seat in 1876. In 1886, the provisions of the law against pretenders to the throne deprived him of his rank as Vice-Admiral, but he continued to live in France, and died of Pneumonia in Paris in June, 17, 1900.

References:

Encyclopedia Britannica (2019). François-Ferdinand-Philippe-Louis-Marie d’Orléans, prince de Joinville, Retrieved April 8, 2019.

Hugo, Victor (2001). The Memoirs of Victor Hugo. Project Gutenberg, Retrieved April 8, 2019.

Lang, H. (2017). Fighting in the Shadows: The Untold Story of Deaf People in the Civil War. Gallaudet University Press. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

Traynor, R. (2015). International Giants of Otology: 19th Century Beginnings, Hearing Health and Technology Matters, Retrieved April 8, 2019.