“I’ve had analog hearing aids for years and my banjo sounded great. They broke recently and I am now trying my fifth set of digital hearing aids. They distort the sound of my music and nothing that the audiologist does seems to help. I am not sure who is more frustrated- me or my audiologist!” This is a common complaint I hear from musicians, and many others. I also hear comments like this from many of my non-musician clients who, on occasion, attend concerts and generally like to listen to music.

The problem is not in the programming software. Tweaking the frequency response, gain, or compression features will only help if they were set up incorrectly for speech in the first place. The problem is the analog-to-digital (A/D) converter that all digital hearing aids have. The A/D converters are found in the normal microphone route, the telecoil route, and the direct audio input route, and depending on the implementation, wireless connection routes. The A/D converter is ubiquitous in modern hearing aid technology.

Partly because of the 16 bit architecture that modern digital hearing aids use, and partly because of some engineering design decisions that had to be made (generally to reduce the noise floor), modern hearing aids cannot handle overly intense inputs- this is typically the case for any input over about 95 dB SPL. This is true of entry-level hearing aids and top-of-the-line premium instruments alike. The most intense components of speech are on the order of the 80-85 dBA, so even shouted speech can get through the A/D converter “doorway” into the hearing aids.

The difficulty lies with music. Even quiet music can have peaks in excess of 95 dBA, and these music elements overdrive the A/D converter (also known as the “front end of the hearing aid”). Distortion that occurs as a result of A/D converters that are not up to the task of transducing music cannot be undone by software manipulation that occurs later in the hearing aid processing system. This front-end distortion does not respond to changes in frequency response, gain, or the hearing aid compression features. Once a sound or music is distorted in this way, nothing will resolve the problem.

This problem is generally worse with instrumental music, but it does occur with vocalists as well. I regularly receive phone calls from singers who feel that their “new top-of-the-line hearing aids” are wonderful for speech, but they can’t seem to get them adjusted for their own voice when singing loudly. It’s the same problem: their voice (which is only inches from their hearing aid microphones) overdrives the front end of the hearing aids.

The hearing aid industry has been aware of this problem for more than a decade (and my own writings about this date back to 2004). Some ingenious responses have been made, including “auto ranging” of the A/D converter to a region that is more appropriate for the music and using less sensitive microphones that “fool” the hearing aid A/D converter into thinking that the input is less intense than it really is.

I have written about this before, but I wanted to share with you some, yet to be published data that show how life can be improved for musicians (and, oh yes, audiologists as well). The Musicians’ Clinics of Canada has just completed a study of another new hearing aid technology that, like the above technologies, seeks to provide the A/D converter with an optimal musical signal that will not create distortion.

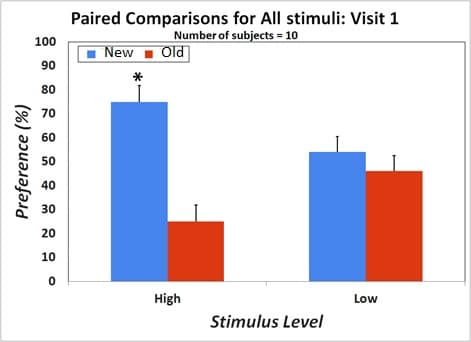

The attached figure shows two sets of bars. On the left is a preference score (from 0-100%) that are the judgments by ten experienced hearing aid users who are professional musicians. The blue bars represent the new technology where there is minimal distortion. The red bars are for an identical hearing aid but without this feature. On the left pair of bars, the music was set at a high level (typical of many forms of music), and on the right pair of bars, the presentation level was at a lower level characteristic of speech.

As would be expected, there was a statistically significant improvement (*) with this newer technology for louder input levels, and minimal differences at more moderate levels of input. This is precisely what this technology was supposed to accomplish.

This new approach is yet another example of how the hearing aid industry is responding (albeit slowly) to the unique requirements of the musicians. Our audiology “tool box” is beginning to grow and I predict that comments such as those at the beginning of this blog, will soon be outdated and rarely heard.

For the hearing aid wearers reading this blog, chat with your hearing health care professional about some of the new approaches that are now available to musicians.

There is nothing wrong with analog. It’s quite capable of delivering very good sound to many of us. I have heard many complaints from friends on their digital aids, that they were not getting anywhere near the clear sound they had for decades. Digital is overly promoted as being superior to analog, and it “fixes” what was never broken in the first place. It may be OK for TVs and computers, but not for those of us who demand top of the line sound quality. Analog technology is sufficiently high, and is still capable of further improvement, and there is no reason analog hearing aids cannot continue to be made for many years to come. Musicians, who live by sound quality, and know whereof they speak, are telling us something very important–digital may be great for speech but it’s lousy for music. It is all well and good for musicians to get new (and probably expensive) technology for their needs, but let’s remember music is an important part of our normal daily experience, too.

Don’t be shy, Marshall! What is this “new hearing aid technology that, like the above technologies, seeks to provide the A/D converter with an optimal musical signal that will not create distortion” and which manufacturer is going to provide it?