Jennifer Shinn, PhD, Professor and Chief of Audiology, Department of Otolaryngology, University of Kentucky Medical Center

Trey Cline, AuD, Clinical Audiologist, Department of Otolaryngology, University of Kentucky Medical Center

Introduction:

As you will remember in Part I, we presented the case of a 39-year-old male who was diagnosed with an auditory processing deficit (APD). He had longstanding difficulties hearing in background noise and with rapidly presented speech. Results of his APD evaluation demonstrated binaural integration, separation and temporal processing deficits along with difficulty with rapidly presented speech. After discussion regarding his management and treatment options, he elected to proceed with both formal auditory therapy and hearing aids.

Formal Therapy Results

As you will recall from Part I, the patient began DIID therapy shortly after his diagnosis of APD. At the initial treatment appointment, the crossover point was established as is required for the DIID training protocol. The crossover point is considered an interaural intensity difference level at which the scores on a dichotic listening task flip and the weaker ear is now performing better on the task compared to the stronger ear. This is established by maintaining the presentation in the weaker ear at 50 dB sensation level (SL) in reference to the speech recognition threshold (SRT) and incrementally decreasing the presentation level of the stronger until the performance flips between ears. The crossover point will generally occur around 20-30 dB IID. The crossover point in our patient was 20 dB IID, therefore therapy was initialed at 25 dB IID.

Initial presentation levels for therapy are a constant 50 dB SL re: SRT in the poorer ear and around 5 dB SL re: to the IID crossover point in the weaker ear. The training can, and should be, completed using a variety of stimuli (i.e. digits, words, etc.). From our clinical experience, 12 sessions over a short period of time yield maximum results (3 sessions/week for 4 weeks or 2 sessions/week for 6 weeks) After the first week of training (approximately 3-4 sessions), the difficulty of the task should be increased by approximately 5 dB. Decreases to the IID to make the task more challenging should be attempted weekly. The goal is to have the patient perform the specified task (binaural integration or separation) within the normal limits bilaterally with a 0 dB IID (equal presentation levels in each ear). Our patient underwent 10 DIID therapy sessions. While this is fewer than the recommended number of therapy sessions, performance on separation and integration tasks was found to be normal at 10 session and therapy was discontinued.

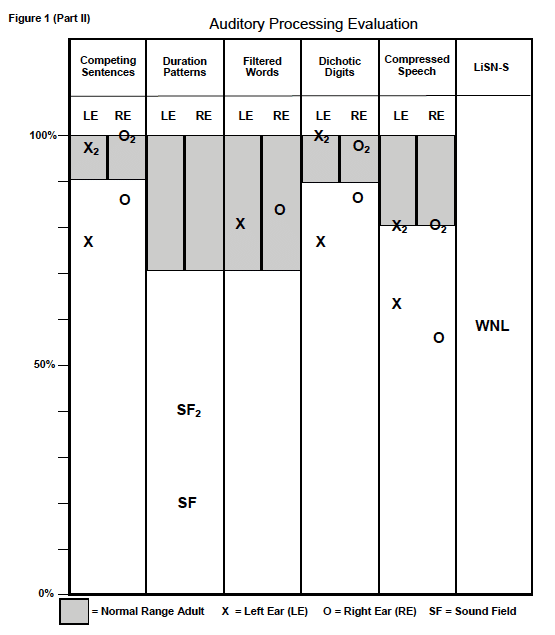

A month prior to his last session he was fit with hearing aids. No formal therapy was administered during his hearing aid trial. He returned for his last therapy session and had completed a re-evaluation of his auditory processing. As seen in Figure 1, significant improvements were observed in both his binaural integration, separation performance. Compressed speech also improved to within normal limits. In addition, while still not within normal limits, the temporal processing scores improved as compared to pre-treatment, even though this was not an area targeted during therapy.

Hearing Aids and Auditory Processing Disorders

It is time to discuss one of the key approaches that have assisted many of our patients with auditory processing deficits. It may be surprising to the reader to that a discussion of hearing aids is included in an article regarding auditory processing. It has been our experience that adult patients with normal peripheral hearing sensitivity and an APD diagnosis do exceptionally when fit with mild gain amplification.

While limited, there is literature to support the use of hearing aids in patients with APD. In 2016, Kokx and colleagues report that patients diagnosed with APD yes had normal peripheral hearing sensitivity demonstrated benefit from the use of mild gain amplification. More recently Roup and colleagues (2019) present a case report of patient with APD who was fit with hearing aids. The patient reported improved quality of life and demonstrated improved auditory processing skills.

Hearing Aid Fitting and Performance

Upon completion of DIID training, the patient showed significant improvements in binaural integration skills as expected. It was recommended that the patient complete a trial of binaural amplification to which he agreed. The patient was fit with a pair of midlevel receiver in the ear hearing aids with a remote microphone. The hearing aids were programmed in an open-fit dome configuration and, although the patient had normal peripheral hearing sensitivity, was programmed based on a mild high-frequency sensorineural hearing loss (1500 Hz and beyond). The programming was completed based on the high-frequency hearing with the goal of providing improved clarity of speech by having greater access to many soft, consonant sounds.

Silber et al. (2015) demonstrated the importance of high frequency audibility in normal hearing adults based on various listening conditions. The researchers showed that additional high frequency audibility is required to achieve optimal performance on speech material (sentences, words, etc.) in the presence of background noise versus quiet conditions with the critical frequency in noise being around 1750 Hz. They also compared auditory-visual verses auditory only conditions and again, demonstrated that increased high-frequency audibility is necessary for improved performance in the auditory only condition. This is particularly relevant with the current use of masks related to the COVID pandemic. Additionally, the patient was programmed in a full-directional microphone array in order to help improve his signal-to-noise ratio. Goyette et al. (2018) demonstrated improved speech-in-noise performance with increased directionality settings on hearing aids in normal-hearing and hearing-impaired listeners.

Subjective Improvements

As important as objective improvements on test performance are, the patient’s report of functional benefit is also necessary. At his two-week follow-up, the patient had reported tremendous improvement in his communication ability. Specifically, he noted that speech was much clearer and easier to follow. He was not working near as hard to communicate in difficult environments. He reported not only that his speech understanding was much improved, but also that his verbal responses were much more accurate and efficient. This gave his conversations much more natural flow with fewer errors or need for repetition by either party. Overall, he was extremely pleased with his binaural amplification and continued beyond the hearing aid trial.

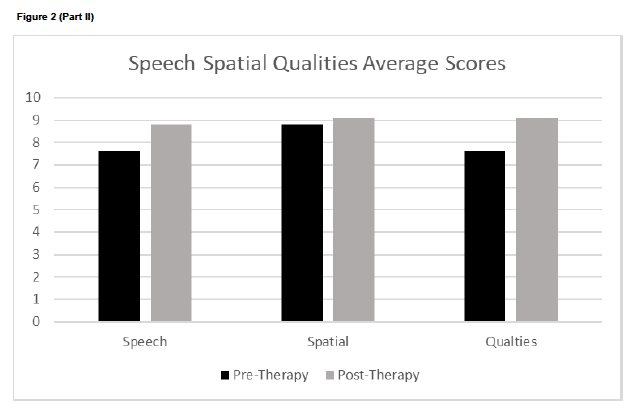

The patient was asked to complete the Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing Scale (SSQ) (Gatehouse and Noble, 2004) pre- and post-treatment. The SSQ is self-report questionnaire designed to evaluate hearing difficulties across the domains of speech, spatial hearing, qualities of hearing. We ask that all patients completed the questionnaire prior to formal therapy or obtaining hearing aids for their APD. Figure 2 demonstrates changes in SSQ performance following treatment and amplification. The patient reported improved function across all three domains following treatment and management for his APD.

Summary

In this two part series, we discuss the evaluation and management of APD in an adult. Our patient, as have many others, demonstrated significant improvement in his auditory function following DIID therapy. In addition, he found significant benefit from the use of hearing aids to assist in managing his APD. In our clinical experience, these are results that we often find in our adults with APD who either undergo formal and/or are fit with hearing aids.

Successful outcomes for adults with APD relies on many variables the include clinicians expertise and resources. In addition, a significant part of the success of the patient depends on their motivation. In this case example, we had a highly motivated patient who was willing and able to dedicate the time to therapy and a trial with hearing aids.

There are different approaches that can be taken in the management and/or treatment of adults with APD. One of the most important steps is recognize is that this is not a disorder reserved for children. Many adults have APD and should be presented with appropriate evaluation, management and treatment options.

Pathways Part II, Figure 1[1] Pathways Part II, Figure 2[2]

References

Gatehouse S, Noble W. (2004). The Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing Scale (SSQ). Int J Audiol 43(2): 85-99.

Goyette, A, Crukley, J, Galster, J (2018). The effects of varying directional bandwidth in hearing aid users’ preference and speech-in-noise performance. Am J Audiol, 27(1): 95–103.

Kokx-Ryan M, Nousak J, Jackson J, DeGraba T, Brungart D, Grant K. (2016). Improved management of patients with auditory processing deficits fit with low-gain hearing aids. International Hearing Aid Research Conference; Lake Tahoe, CA

Roup, C, Ross, C, & Whitelaw, G. (2019). Hearing difficulties as a result of traumatic brain injury. J Am Acad Audiol, 31: 137-146.

Silberer AB, Ruth Bentler R, Wu YH (2015). The importance of high-frequency audibility with and without visual cues on speech recognition for listeners with normal hearing. Int J Audiol, 54(11): 865-872.