by Aaron Whiteley & Frank Musiek, University of Arizona

This commentary has been divided into two parts that will be presented in two successive months of Pathways. It is based on the lab work of the first author (AW). The first part will deal primarily with an overview of the actual research related to a particular measurement technique for locating Heschl’s gyrus. Part 2 will discuss the importance of Heschl’s and how can measurement information be applied.

Heschl’s gyrus in humans is an important structure located in the temporal lobe. It is often considered to be the primary auditory cortex. Students in audiology as well as hearing science and related areas of study are expected to understand the location and function of Heschl’s gyrus. Students who have the experience of doing brain dissections as part of their training and education spend time locating Heschl’s also known as the transverse gyrus. Most of the time, with good instruction, students have little problem locating this important structure. However, in some cases the identification of Heschl’s poses a considerable problem, not only to students but even established scientists. This is because Heschl’s can have various morphological presentations including a duplication and in some cases as many as three gyri. In addition, the morphology of the planum temporale (PT), a structure located immediately posterior to Heschl’s can appear similar to Heschl’s. The sulcus separating Heschl’s from PT is sometimes difficult to visually identify, hence further contributing to the challenge of the identification/location of our primary auditory cortex.

The occasional complexity of defining and differentiating Heschl’s gyrus is a challenge that is not new. Those interested auditory neuroanatomy for years have confronted this problem. However, there has been a paucity of published data that has addressed the challenge of locating Heschl’s. Perhaps it has been because the problem has not been common enough or significant enough. However, for those who beginning to learn about neuroanatomy this problem is very real. In this regard a method of locating Heschl’s gyrus has been used in anatomy labs for years but with little fanfare or published documentation. This methodology could be viewed as a “rule of thumb” or perhaps a quick way to locate Heschl’s and is commonly termed the two thirds (2/3) rule.

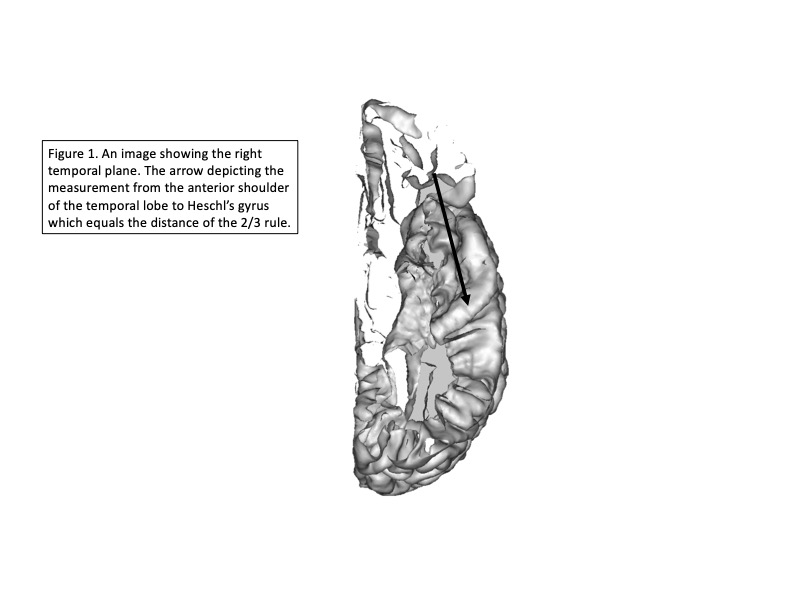

The 2/3 rule requires a measurement that is 2/3 of the distance back (posterior) on the superior temporal plane (Figure 1). This measurement should be placed at or very near Heschl’s gyrus. In our view, this maneuver was not intended to be an exact indicator but rather a quick approximation to guide the student. However, as mentioned earlier, little has been published about the 2/3 rule and to our knowledge little evidence to indicate that it works. Therefore, it seemed compelling to test the 2/3 rule within the guidelines of a planned research project.

Before discussing some of the research it should be mentioned that MRIs not cadaver brains were utilized. This allowed the use of software that was most helpful in making and computing measurements.

One of the factors in determining the value of the 2/3 rule was to first to carefully define the anterior and posterior extent of Heschl’s on the temporal plane. The anterior extent of Heschl was determined by identifying the transverse sulcus and the posterior extent by Heschl’s sulcus. Another consideration was that there can be one or two Heschl’s gyri. If there were two gyri, it was hoped that the 2/3 rule would mark within the extents of the two gyri. The posterior end point of Heschl’s was Heschl’s sulcus was quite easily definable, but the most anterior aspect of the superior temporal plane was more difficult to define. This was decided by projecting the ascending angle of the anterior temporal lobe to where the horizontal angle of the Sylvian fissure meet. This point has also been termed the anterior shoulder of the temporal lobe. From this point measurements were made posteriorly to Heschl’s.

A variety of measurements were made lateral to medial to account for the topographical variability over the temporal plane and the angle of Heschl’s which is also variable. The details of these measurements are beyond the scope of this commentary; however, we will relate the key findings.

One key result of the research was that one must be careful in measuring for the 2/3 rule that the measurement be essentially be halfway between the lateral surface and most medial aspect of the temporal plane. If this is done the 2/3 rule is indeed accurate. This procedure will place the 2/3 measurement end point within Heschl’s gyrus. However, if one does not follow the half-way (essentially the middle of the temporal plane) guide the 2/3 rule is not as accurate. The 2/3 rule appears equally accurate for both left and right temporal planes.

… To Be Continued