HHTM Staff: The leprosy series comes to an end today with a look at what is known of leprosy’s effects on the vestibulocochlear nerve (VIIIn) and into the brain. Sensorineural hearing loss without vestibular symptoms is associated with leprosy, independent of antibiotic treatment. Hearing loss is likely under-reported; likewise, leprosy itself likely goes undetected for years in many who have it. In the US, over 200 “new” cases are identified each year.

Efforts to determine site of lesion effects of leprosy on the auditory system remain up in the air. Last post commented that researchers’ conclusions that the effects are cochlear or neural are open for debate. Likewise, today’s post describes why peripheral versus central neural loci are debatable, especially when other neural diseases are present.

Central Neural?

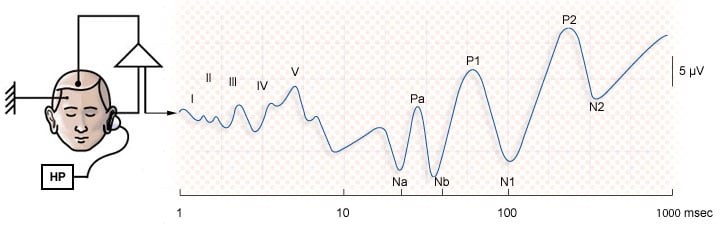

A few ABR studies have attempted to refine the auditory neural hypothesis in leprosy patients, with equivocal results. Celik et al. (1997) found abnormal ABR results in 38 leprosy subjects with normal audiometric thresholds compared to 40 age-matched controls. All leprosy subjects had histories of ongoing dapsone treatment. The authors assumed a neural origin when interpreting their data even though the main effect was prolongation of wave I. An alternative explanation of peripheral cause was not ruled out or discussed. A statistically weak secondary effect of III-V interpeak latency increase was interpreted as evidence of central (high brainstem) neural involvement.

In contrast to Celik et al’s findings, Kochar et al (1997) found normal wave I and delayed wave V average latencies in 25 subjects with newly-diagnosed leprosy, compared to 25 age and sex-matched controls. The observed effect was mainly due to III-V delay, which does support the notion of a central, high brainstem effect in those with Hansen’s disease. Audiometry was performed on all subjects and controls, but results were not reported, although normal hearing seems implied. Likewise, absence of antibiotic treatment as a confounding factor seems implied.

In sum, the conclusion that ascending auditory pathways are affected by leprosy in the absence or presence of sensorineural hearing loss remains open to debate.

A Final Twist

The assumption that leprosy affects the eighth nerve in some patients is further confounded in patients with neurofibromatosis, another disease manifest by extreme disfigurement, skin growths and stigma. The two diseases are quite different — one is bacterial, the other is genetic but symptoms make it easy to confuse, misdiagnose and mistreat one for the another (Dharmendra et al, 1925).

Neurofibromatosis I (NFI, von Recklinghausen) is known to co-exist with leprosy. NFI expresses in a wide variety of ways, but vestibular schwannomas are not symptomatic of NFI. On the other hand, the hallmark of neurofibromatosis II (NFII, confusingly called “central” von Recklinghausen disease in some reports) is its attack on the vestibulocochlear nerve, CN VIII. NFII is much rarer than NFI. NFII data comes from case reports demonstrating bilateral acoustic neuromas (vestibular schwannomas) present with imaging. However, reference is made to unilateral vestibular schwannomas as part of the diagnostic screening process.

NFII can co-exist with leprosy. Dogra et al (2001) describe a case of bilateral sensorineural hearing loss observed in a patient diagnosed with leprosy. However, the patient also presented with vestibular symptoms, which are not associated with leprosy. Subsequent imaging studies revealed bilateral vestibular schwannomas. NFII was diagnosed, prompting this caution form the authors:

“audiovestibular symptoms in leprosy may not always be related to the primary disease… a high index of suspicion should be kept in a leprosy patient who has vestibular symptoms associated with sensorineural deafness.”

In sum, the conclusion that leprosy causes VIIIn disorders remains open to debate, especially if vestibular symptoms are present.

What Should Audiologists Know? What Should Audiologists Do?

The point of the infections diseases series is to raise awareness among global travelers and audiologists that so-called “exotic” diseases can and do exist. Travelers can be exposed as they explore the world; newly arrived immigrants can bring old diseases to developed nations. Most healthcare professionals in the US are not trained to recognize or even inquire about such diseases. Certainly, most audiologists are not thinking of such diseases when they take histories or do follow-up evaluations.

Ebola outbreaks and transmission have made it clear that there are risks as well as obvious benefits to living in an increasingly interconnected world. Leprosy is one of those risks but it is an easily treated risk so long as healthcare workers ask for travel histories and are aware of how the disease manifests.

Audiologists should ask patients about travel histories and general health during initial history-taking and subsequently at follow-up visits. Inflammation of the pinna should be observed as part of otoscopic examination. Presence of sensorineural hearing loss without vestibular symptoms should be communicated to the patient’s primary care physician, along with notation regarding other contributing history (e.g., noise exposure, ototoxicity, familial history) and any retrocochlear findings.

This is Audiology 101 but it’s worth reminding Audiologists of the importance of basic reporting; also of adding the global travel component to the history and reporting. And, as always, be sure to observe infection control guidelines outlined for Audiology practices, yet another part of Audiology 101.

Feature Image courtesy of Audition Cochlea Promenade

References

Celik, O, et al. Auditory brain stem evoked potentials in patients with leprosy. Int’l J of Leprosy, 1997; 65(2), 166-169.

Dharmendra. A case of leprosy wrongly diagnosed as neurofibroma. Lepr. India 24(1925)160-163 (see summary review).

Dogra S et al. Leprosy and Neurofibromatosis 2: what is common? Int’l J Leprosy, 2001; 69(3), 251-2.

Kochar, DK et al. Study of brain stem auditory-evoked potentials (BAEPs) and visual-evoked potentials (VEPs) in leprosy. Int’l J Lepr, 1997;65(2):157-65.