For years, dispensing audiologists have been cautioning patients and parents to take care around hearing aid batteries. The threat of accidentally ingesting a battery was a real one and posed significant danger when batteries contained mercury. The caution was codified in the FDA hearing aid information booklet that is still part of every hearing aid dispensing transaction and is required reading for patients and/or parents of children fitted with amplification.

Nowadays, the advent of Lithium-ion batteries (Li-ion) has introduced new concerns and cautions for audiologists to share with patients. Some practical aspects of battery storage and transport were discussed in a previous post. Today continues the discussion by briefly touching on changes in battery technologies. Readers who want in-depth discussion of battery design and application are referred to an extensive series of posts at Wayne’s World (see links at end of this post).

Swallowing Hearing Aid Batteries

When mercury-free hearing aid batteries became the norm in 2011, audiologists thought the risk from battery ingestion was greatly reduced. Though that was so for risk of mercury poisoning, it is not the case for other problems brought about by ingesting button batteries of all types. According to a Medscape review of an research article published in Pediatrics:

The number and rate of battery-related emergency department (ED) visits for children younger than 18 years nearly doubled between 1990 and 2009. The risks were highest for children younger than 5 years and often involved the small, coin-like batteries that power toys, games, and watches and for younger children.

… And we might add, hearing aids. The study clocked over 65,000 children taken for battery-related emergency visits over a 20 year period. A fifth of those children were age one or younger. The review confirms that most batteries pass harmlessly through the digestive tract, but it also pointed out that the big danger is when button batteries become lodged in the esophagus where they

“can damage surrounding tissue by several mechanisms, most importantly by causing electrolysis of tissue fluids and generating hydroxide at the battery’s negative pole.”

As in the past, audiologists must remain mindful to remind their patients and patients’ families to:

- Keep batteries in a safe place, away from children, pets and those with vision or cognitive difficulties;

- NOT put used batteries in old prescription bottles;

- Bring used batteries in for recycling.

Exploding Batteries

At present, it’s the rechargeable Lithium-ion batteries that are making the news for exploding in headphones and Samsung cell phones. But, it’s worth noting that even zinc-air batteries can explode under the right circumstances. Those circumstances have to do with poor design or manufacturing, which is why batches of Chinese-manufacturered zinc-air batteries were recalled in the UK in 2016.

The reason that Li-ion batteries are more subject to fire and explosion is because they’re more prone to overheat due to a variety of reasons having to do with physics and battery construction. The Verge has a great article that explains the basic mechanism of Li-ion batteries and lists reasons for failure in the form of explosion. Portions of that article are summarized here.

How Li-Ion Batteries Work

Two opposing- but never touching- electrodes, called the cathode and anode, hold positive and negatively-charged ions respectively. Lithium is stored in the cathode side of this arrangement. The travel of lithium ions between the electrodes is what makes the battery manufacture energy.

When the battery is charging, ions move to the anode; when the battery is in use, they move back to the cathode. All travel is rapid, aided by electrolytic chemical conductors in the space between the cathode and anode. The faster the molecular motion, the more energy and heat manufactured by the process.

How Li-Ion Batteries Can Fail

- If the electrodes touch, the ionic energy gets redirected to the electrolytes in between, heat happens, electrolytes react which creates more heat, explosion is almost inevitable. Separators are inserted between cathode and anode to prevent this worst possible type of failure.

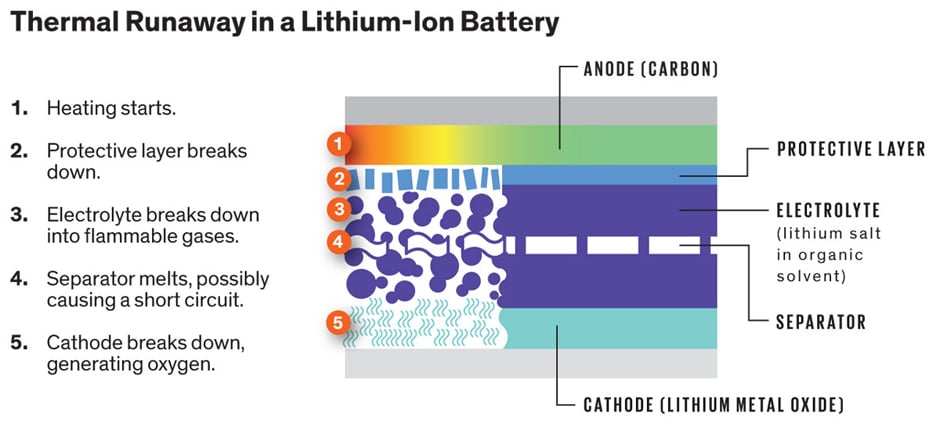

- If it’s too hot outside, the electrolytes between the cathode and anode become increasingly unstable. They react, create more heat, and initiate an “uncontrolled positive feedback loop” which ends up in fire and explosion by reducing the external heat source. This “thermal runaway” happens even if the cathode and anode are not touching (see Fig 1).

- If batteries are charged too fast, too much lithium gets shuttled over to the anode, causing an imbalance which can short-circuit the battery, leading to fire and/or battery destruction.

Knowing the architecture and a bit about theromodynamics, it seems simple to build Li-ion batteries that don’t fail: make sure the separators are in place, don’t heat up the place, monitor the rate of charge. That’s probably right, except that everybody wants the batteries to generate energy for a long time without recharging and they want them to be so tiny they can fit into hearing aids that need most of their real estate for other matters, like processing speech in noise and handling feedback. And, of course, they want the batteries to be inexpensive and last a long time. Hmmmm.

Reasons Failures Occur

By their very nature, Li-ion batteries can explode. But the probability of their doing so is very low–probably much lower than accidentally ingesting one. By report, those that exploded in Samsung phones did so because of a manufacturing defect.

Zpower, which manufacturers an alternative to Li-ion batteries, lists the following explanations for why they might go into overdrive, overheat and explode:

- Flawed battery design

- inadequate manufacturing quality

- improper charging/discharging

- physical abuse

Coupled with any or all of these possibilities, Zpower acknowledges “a classic trade-off between performance and safety” which certainly puts hearing aid batteries in the cross-hairs of this discussion. As Wired magazine puts it (and not just for hearing aid batteries):

“…they seem to get more volatile as time goes on. That’s because we demand higher-capacity batteries in slimmer packages at cheaper prices. …As a result, many lithium-ion battery manufacturers cut corners in order to price their cells more cheaply. The materials may have imperfections, causing damage in the already-thin separator.”

Current and Future Energy Alternatives for Hearing Aids

The hearing aid industry is going all out for rechargeable technology and HHTM has heard of no reports of exploding batteries. Financial analysts at Bernstein Research Co had this to say after visiting the exhibit hall at last month’s AudiologyNow! conference in Indianapolis, put on by the American Academy of Audiology:

“The industry is moving towards rechargeable hearing aids in earnest …We think that the ability to offer more than 24 hours battery life is a game changer for the technology.”

Zpower manufacturers an rechargeable alternative to Li-ion batteries for hearing aids. The Zpower rechargeable system for hearing aids is a silver-zinc battery characterized as “stable, non-flammable, and non-toxic” in addition to being more efficient (greater energy density) than equivalent Li-ion cells. This system has been reported and described in detail in posts publised at HHTM in 2016 and 2017.

Today’s post is about the cautions and concerns surrounding the transition to rechargeable batteries for hearing aids. As in the past with concerns about toxicity of mercury batteries, concerns with new technology are being addressed and solutions are forthcoming. Of more interest in the long run is the remarkable strides that have been made in battery cell technology over the years, for hearing aids and other personal electronics devices.

Wayne Staab has written extensively at HHTM on battery technologies of the past, present and future. Readers are referred to his section, Wayne’s World, for in-depth discussion of hearing aid battery technology, including the possibility of refueling rather than recharging in future energy sources. An extensive list of posts by Dr Staab and others can be found in the reference list provided by Barry Freeman in his February 2, 2017, post on emerging rechargeable battery technologies for hearing aids.

References

Chen A & Goode L. The science behind exploding phone batteries; It’s natural for battery chemicals to want to explode. The Verge, Oct 13, 2016.

Clive LB, Wielechowski R & Morse A. Hearing Aids: Feedback from the Audiology Now! conference. Thoughts on the latest technology and OTC hearing aids. AllianceBernstein,LP, April 12 2017.

How Safe are Lithium Ion Batteries? Are There Safer Alternatives? Zpowerhearing.com. November 14, 2016

Sharpe, Rochett & Smith. Pediatric battery-related emergency department visits in the United States, 1990–2009. Pediatrics, 129(6). June 1, 2012, pp. 1111 -1117. (doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0012)

St John A. Why Lithium-Ion Batteries Still Explode, and What’s Being Done to Fix the Problem. Consumer Reports. September 21, 2016

images courtesy of adafruit and ExtremeTech

Interesting overview of pitfalls associated with li-ion rechargeable batteries. It’s not explicitly stated but implied that li-ion hearing batteries present the same hazards as those used to power laptops and large screen cell phones. I would like to see a meaningful comparison of the large batteries in such devices vs the li-ion cells used in current hearing aids. Additionally, I am left with the impression that this post was sponsored by Zpower. Seems like their tech is being presented without a balanced look at the pros and cons.

This post was not sponsored by ZPower, but that emerging techology in the hearing aid sector has received a good deal of attention at HHTM and elsewhere in the industry in the last two years, hence those posts are referred to as part of this update. Thank you for asking so we could clarify this. HHTM does not published sponsored posts. On a rare occasion, sponsored posts could appear but they would be prominently identified as such, and probably called “advertorials.”