Starting in 2010 Dr Frank Lin and colleagues commenced publishing results of studies of hearing loss and dementia, arriving at essentially the same conclusions using two paradigms and two different, large subject cohorts. At the time, a Huffington Post article provided a good summary for lay readers of two studies loosely referred to as The Johns Hopkins Study and The Health ABC Study Hearing Cohort Study.

Here is a summary of the Johns Hopkins Study (references below) for audiologists, who are encouraged to read it in full. It forms a bedrock for subsequent and ongoing studies by the Lin group at Johns Hopkins.

Hearing Loss & Dementia: The Johns Hopkins Study

The objective was “To determine whether hearing loss is associated with incident all-cause dementia and Alzheimer disease (AD). ” The way the authors stated it is important to bear in mind: not all dementia is due to Alzheimer’s.

Design

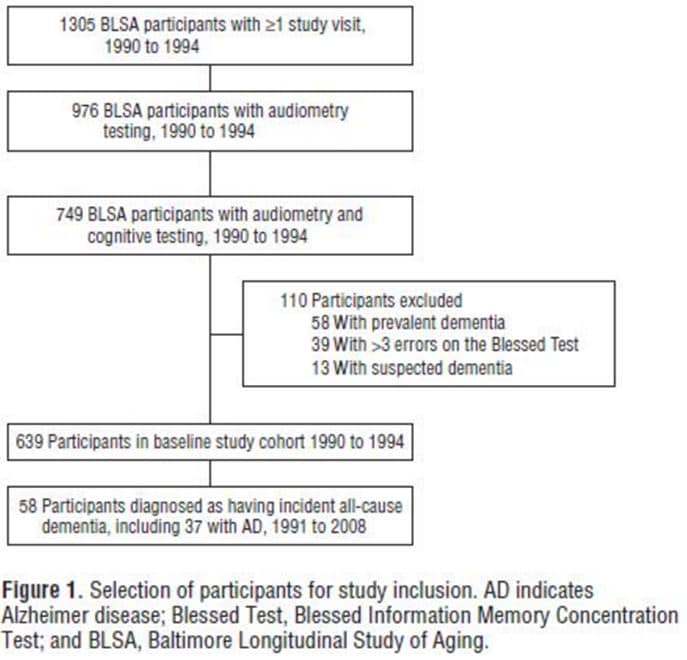

A total of 639 subjects, aged 36 to 90 years, were culled from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging (BLSA), a prospective NIH study ongoing since 1958. All participated in hearing and cognitive tests in the study during the 1990-1994 time frame; none showed signs of dementia by test or observation when they were selected (see flow chart in Fig 1 from the published article).

A total of 639 subjects, aged 36 to 90 years, were culled from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging (BLSA), a prospective NIH study ongoing since 1958. All participated in hearing and cognitive tests in the study during the 1990-1994 time frame; none showed signs of dementia by test or observation when they were selected (see flow chart in Fig 1 from the published article).

The subjects were followed for over a decade (median = 11.9 years). Besides hearing and cognitive status, the study measured and controlled for other variables that could influence cognition or hearing and confound results: diabetes, blood pressure, blood pressure medication, sex, race, education, smoking, and hearing aid use. The latter two variables were not measured directly but were based on subjects’ self reports. Also, and importantly, hearing aid self report data was missing for 72 of the subjects.

Results

By the end of the study, over 9% (58/639) of the participants had some form of dementia (“all cause”). Alzheimer’s was present in 5.8% of the total group (37/639), accounting for 63.8% of all dementias 37/58).

The majority of subjects (455/639) had normal hearing at the beginning of the study. Most of the 184 subjects with hearing loss were males (135). They were also older, on average, and more likely to have high blood pressure. The question was, were those with hearing loss at the start of the study more likely to develop dementias over the study’s span, compared to their normal-hearing counterparts, and independent of other variables?

Although some of those with normal hearing undoubtedly developed hearing loss during the 11+ year study, hearing status was not rechecked at the end of the study, so the question does not ask whether increasing hearing loss over time is associated with changes in cognition or changes in the covariables.

Here’s what the researchers found:

- Dementia was linked to age, hypertension and hearing loss. It was also linked to hearing aid use (which does not mean that hearing aids cause dementia).

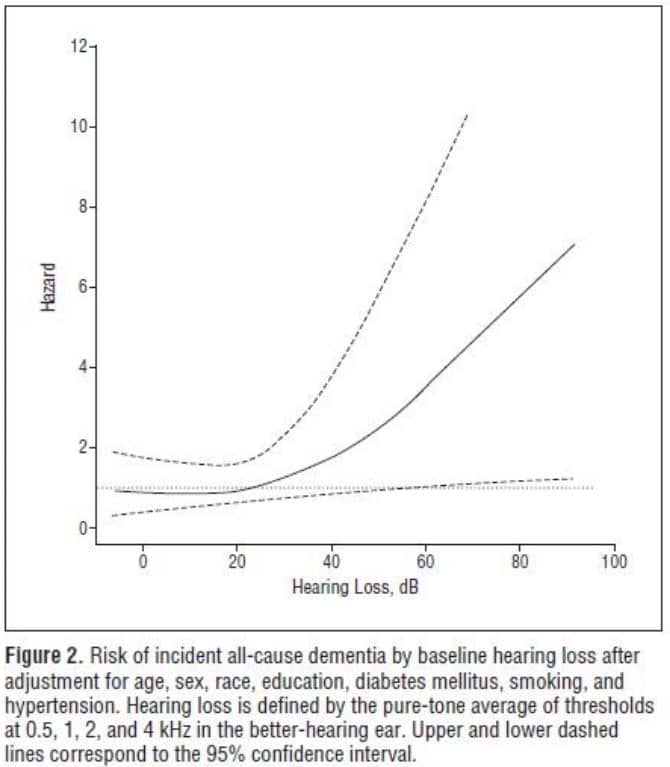

- Participants with hearing loss were more at risk (greater hazard, see fig 2) than those without hearing loss to develop dementia, independent of the other variables.

- For those >60 years old, more than 1/3 of the risk of dementia was independently associated with hearing loss.

- The greater the hearing loss, the higher the likelihood of developing dementia.

- Specifically, risk of dementia increased by about 20% for every additional 10 dB of hearing loss.

- The 20% risk increase per 10 dB of hearing loss was the same for Alzheimer’s disease as it was for dementias in general.

Hearing Loss and Cognition: What Do These Findings Mean?

First, they do not form a causal link between hearing loss and dementia: we don’t know whether hearing loss causes dementia or vice versa, or neither causes the other. We just know that they are likely to be linked in at least 1/3 of those who develop dementia. As always, correlation is not causation.

Regression statistics are tricky. The way to interpret Figure 2 is that among those who were identified as having hearing loss, the “hazard ratio” of developing dementia was greater than the rest of the group, and likelihood increased (coefficient of 1.20) with increasing amounts of hearing loss at the outset. That is what is shown in Figure 2 by the rising solid line.

As you can tell from the numbers in the cohort, most with hearing loss did NOT develop dementia, regardless of degree of hearing loss at the outset, but the incidence was statistically higher for HL group than overall group.

We also don’t have much if any basis to connect use or non-use of hearing aids to risk of dementia. The data were sparse and based on self report. The authors pointed to this as a weakness of the study but they weren’t really studying corrected hearing loss anyway. It’s was not as much a weakness as it was a spur for future research.

References & Footnotes

Lin FR et al. Hearing Loss and Incident Dementia. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(2):214-220. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2010.362.

Lin FR et al. Hearing Loss and Cognitive Decline in Older Adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(4):293-299. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1868.

This is a great article!

It’s a shame to let the variable of amplification history go by the wayside in this study. It leaves observers to conclude that hearing aids do nothing to help the dementia issue–kind of a two-edge interpretive sword: on one hand the authors noted in their original report that earlier hearing correction could possibly diminish the risk of dementia (implying a cause-effect).

On the other hand, not ascertaining the hearing aid experience and its influence on cases of dementia leaves one to erroneously conclude that if you wear hearing aids you will suffer greater brain shrinkage or, at least the symptomatic counterparts, dementia.

Now, what I propose is that the authors conduct a sample qualitative study from the group and under the lens of case history, find out how long the hearing loss progression existed (experience tells us about 10-20 years before hearing aids are considered), whether the correction matched the diagnostics (monaural vs binaural), degree of continuous (full-time) hearing aid use (and compliance), how often the fitting was updated (if at all), other mitigating factors that cause brain shrinkage, such as hypertensive drugs, or other neurodegenerative effects (NSAIDs, Reflux Meds, Neuroleptics, Statin drugs, Insulin-inspiring drugs, etc.), and finally, how much their hearing loss had changed over the 11 year period. Granted some of this information would take a high level of knowledge (and time) on the part of the data gatherers. But when we are expected to infer study results into real life trends, we need to know in thorough, objective terms the relevancy of the study to real life application.

I must say the study was a ground breaker in it’s own right and added incredibly important insight into the corrosive effects of untreated hearing loss. Put this together with the University of Texas-Austin studies back in the 1980s and 1990s, the more recent Brandeis studies relative to the burning of brain glucose during hearing and tinnitus tasks, and the wonderful work out of the 1990s from the University of Pittsburgh (the list is quite long, really) the Johns Hopkins study brings much needed fresh light to the topic.