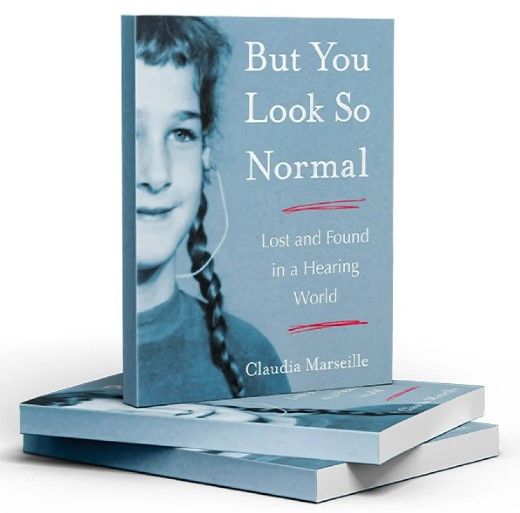

This week, Gael Hannan sits down with Claudia Marseille, the author of the new memoir “But You Look So Normal: Lost and Found in the Hearing World.” Claudia shares her journey of growing up with severe hearing loss, being diagnosed at the age of 4, and overcoming numerous challenges with determination and technology.

She talks about the inspiration behind her memoir’s title, reflecting on the frequent comments she received about her normal appearance despite her hearing loss. Claudia discusses the profound impact of hearing loss on her relationships, her struggle with loneliness, and how her support network, including her brother and close friends, played a crucial role in her life. Gael and Claudia explore various aspects of living with hearing loss, from childhood experiences to adult life, including the challenges in professional settings before the Americans with Disabilities Act.

She talks about the inspiration behind her memoir’s title, reflecting on the frequent comments she received about her normal appearance despite her hearing loss. Claudia discusses the profound impact of hearing loss on her relationships, her struggle with loneliness, and how her support network, including her brother and close friends, played a crucial role in her life. Gael and Claudia explore various aspects of living with hearing loss, from childhood experiences to adult life, including the challenges in professional settings before the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Claudia also shares her artistic journey, highlighting how her hearing loss influenced her transition to visual arts and writing.

Full Episode Transcript

Hello. Welcome to this week in hearing. I’m Gael Hannan. I am so thrilled to welcome, as our guest this week, Claudia Marseille. She is the author of the just published memoir. It’s called ‘But You Look So Normal’. Lost and Found in the Hearing World. Claudia was diagnosed with severe hearing loss at the age of four. But thanks to determination and technology, she learned to hear, to speak, and to speech read. Claudia holds Master’s degrees in archaeology, public policy, and fine arts. She is an artist. She is a photographer, she’s a painter, and now she is an author. So welcome, Claudia. I’m so thrilled that you’re here. Thank you, Gael, so much. I’m thrilled to be here and to finally meet you. I’ve been a great admirer of you and your work. Well, thank you, thank you. And now you are a fellow author. This is wonderful. can you hold the book up for us? You probably have an advance copy, but you look so normal. Wow. And just the back. Just the back. I love books. Okay, this is great. I have to ask you. So, yeah, thanks for sharing. That’s wonderful. Why did you call it: But You Look So Normal? Tell me about that. Well, in my early years particularly when I was in middle school, and I finally got the first powerful behind the ear hearing aids, my hair was cut short, so it was hidden like it is now. And for years, I hid my hearing loss, which is not a good strategy at all. And by the end of high school, people always thought I was a little odd, a little bit out of it. They didn’t quite know what was how come I didn’t respond appropriately in some situations. So the real turning point for me was in my 12th grade English class when I had an English teacher with a very thick accent, mustache over his mouth, I couldn’t lipread. He was playing LP records of Shakespeare plays by Hamlet, you know, Othello and Macbeth. And he wanted us to close our eyes and take in the language and just listen. And I was doomed. I didn’t have a text to read. I couldn’t lip read it with hopeless situations. So out of desperation, I went up to him after class and said, you know, I am really hard of hearing, and I really need to be able to read the text. And he said, “oh, but you look so normal.” And I remember thinking, wow, what does someone think a person with a hearing loss would look like? And then I got this many times over the years in college when I would finally tell a friend that I was hard of hearing. And again, oh, you look so, so normal. so that kind of stuck in my head, and I thought that would be an appropriate title for the book. Well, you know, I think that if I had received those comments, I would have written my first book that as well. But I always got, oh, you’d never know it. As if that was a good thing. Right? So well, but you look so normal, lost and found in the hearing world. I can’t wait to read it. I want to. Well, actually, I have. I’ve scanned through the advanced information that you sent me, and I am really fascinated about the impact of hearing loss on a relationship. And you spend a lot of the first part of the memoir about your childhood and your relationship with your parents, and I’d love to hear more about that. Well, one of the things I want to point out in all of this is that loneliness is probably the hardest obstacle and impact that my hearing loss has had on me. Loneliness is a big epidemic in this country. The surgeon general has written about it, and it cuts across all age groups, elderly and teenagers. So obviously, it’s not just to hearing loss. But I mentioned that because that was the thing I struggled with in relationships. you know, I was cut off from my peers. They didn’t necessarily bully me or were mean to me. I was just kind of left out of social girl interaction. and even in the classroom, when there would be group discussions in the classroom, there’s a level of sociability and learning that I was just not able to participate in. In the school cafeterias, I couldn’t understand what the kids were talking about with the noisy, noisy background of the cafeterias. So within my family, my mother wanted me to be as normal as possible, and she just didn’t. She was under her own stress of being a Jewish immigrant from Germany, and my father, likewise from Germany, they had their own stresses. They were going through a divorce. So they didn’t advocate for me as they should have and could have. And as a lot of parents today advocate for their children. My brother was very attuned to me. He was just two years younger than me, and he knew that he had to turn and look at me so that I could lip read. He would introduce me to the other kids in the neighborhood, explain what the games were, what the rules were. and so he was my first major advocate as a kind of transition into the world. And I always had one best friend who would play that role for me, and they often didn’t know that that was the role they played. I was desperate for that, but I was also kind of able to not make it too obvious how dependent I was on them. So in terms of the impact of relationships, I had sort of one on one relationships with people, and that made a difference. But in terms of slumber parties, I was totally out, and that was very painful. The lights would be turned off. I couldn’t live reading in the dark. Girls would be whispering about all kinds of things, and I was left out. Group cliques at school, in middle school, same thing. So and it kind of cuts across even to today, I’m not great at big group discussions and interactions. So I’ve cultivated one on one friends. You know, that as you were describing growing up and all of that, just, I could just feel my old anxieties as a child, as a teenager coming to the fore. But it’s really clear that you developed, or you developed a support network, and it was a small support network, but it was a strong one for you. So with that, with your brother and with that one best friend. So. And I think that’s so important for people with hearing loss to have that support network whether it’s best friends and our partners in life, that sort of thing. Definitely. And even with boys, it was interesting. I always had to gravitate towards a boyfriend who had a certain tolerance for my hearing loss. And so it usually was not a boyfriend who was socially extroverted and out there and hanging out with his buddies with lots of groups and people that would not be somebody that I could have had a relationship with. It was more of an introverted, quiet kind of guy. And that’s what I ended up with, with my current husband, who has been very supportive of me. How many husbands have you had? I had a one short lived husband in England, and we lived in England, and he was good in terms of what we’re talking about. In terms of in England, I could not use the phone in general, I could not use the phone until recently with Bluetooth technology. But he was great in making phone calls on my behalf. But yeah, that’s a good reason to marry someone. I need someone to make phone calls for me. Right. So, you know, as human beings, there’s always reasons that we choose the people in our life, but sometimes people just happen to us, and sometimes we fall in love with the wrong person. But by and large, for a successful relationship, there are certain things, right, that have to be in place, such as, can I understand this person? So presumably husband number two is someone you can understand. Maybe he still makes phone calls for you. I know mine does. So, yes. And as I said, the technology has also made a big difference in terms of the ability to connect better with other people. And Zoom has been terrific because you can both see and lip read, and I can use the Bluetooth technology through my computer into my hearing aid and also with the phone. So my lifelong phone phobia ended when Bluetooth came out. I agree. We are on Zoom right now. We are both streaming through Bluetooth. The problem I’ve had, we also have a landline. And why, I don’t know, but if the landline rings and because everything connected through my phone now I need to go to telecoil so that I can pick up. And I’m generally not closing up to anyway, so I just ignore the landline calls, to be honest with you. And I just Anyway, so technology is fantastic, but there’s still limitations. It’s not perfect by any means. Yes, when I was a kid, I had a telecoil, but the buzz of the telecoil was so loud that I was not able to hear the person on the other end. And, you know, back to relationships. That was difficult because kids especially girls, spend hours on the phone talking and group talks and whatever, and I couldn’t, I couldn’t participate in that. Kids were listening to transistor radios on that time and talking about lyrics and bands and music, and that was a whole level of teenage culture that I was not part of. Yeah, I empathize with that. I have my own set of lyrics to almost every song I ever heard until they started printing lyrics on the album covers or something. But before, before that even now, if I’m singing to myself, I sing nonsense lyrics because I don’t know what the real ones are. Sometimes mine turn out to be better. Anyway. so with relationships were you always open about your hearing loss or does it take you time to let people know that you have some challenges, perhaps, in communicating with them? Well, and this was this was a difficult thing for me because in elementary school, it was obvious I had a hearing loss. I had a big primitive analog hearing aid clipped to my undershirt, tied on with straps. I had an electrical cord going to a custom made mold. And so all the teachers and the classmates knew that I had a hearing aid and that was a good thing. So that kind of explained to them when I was a little bit out of it what the situation was. But then, as I said, when I went to middle school, I had my hair cut short like it is now, and the first behind the ear hearing aid, where I suddenly was able to hear with two ears, which I hadn’t before, and that did help. And then I guess because of teenage shyness. And also there was kind of a stigma of hearing loss at that time, which is really much, much less now as so many of us and baby boomers and everybody’s wearing hearing aids. So that has really kind of minimized the stigma. But at the time, I was the only person I knew growing up that had a hearing loss. I did not meet another deaf or hard of hearing person until my mid thirties, and I’m not exaggerating. And that again, in terms of affecting relationships, it would have been nice to share that experience with someone else. I went to a big public high school in Berkeley with 4000 students. They may well have been another person with a hearing loss there. I just didn’t know. So I hid that during high school until, as I said, I described that being with my teacher. And then by the time I was in college, I was telling people more and people, you know, they understood. Sometimes they would say, oh, I thought you were stoned, you know, that. but then when I had my initial jobs in public policy, that was challenging because at that time, that was long before the Americans with Disabilities Act, which would provide some accommodation on the job in the classroom and the California Deaf Children’s Bill of Rights act. So this was long before that, it was long before Internet and long before emailing, so I would have to use the phone to get information. And that was so, so stressful. And I would not tell my lovely bosses and colleagues I had a hearing loss because I was afraid of jeopardizing my job, which was a real consideration. Yeah, it can be a real concern. So let’s move away from the stressful stuff for the moment. You’re an artist. and I’ve seen your paintings and I just love them. do you see a connection or a mutual the impact of hearing loss on your art or vice versa? Is there a connection in your life between hearing loss and art? You know, that’s so interesting. I ended up in art after my family is very high powered and has high standards and doctor, lawyer, whatever was the way to go. and so I had a lot of different professional attempt, archaeology, public policy. And I was struggling so hard in those professions and I always loved drawing, and I always loved photography since I was a teenager. But I could never afford the cost of going to art school. And it was really my second husband who encouraged me to do that. And he said, you know, I think this would be compatible with the hearing loss. So I often paint with my hearing aid turned off so that I’m in the world of silence, where I feel very comfortable. I do abstract paintings. So my art isn’t directly related to hearing loss per se in terms of subject matter, but in terms of the creative process. There’s something about being in silence and mining what’s inside of me and bringing that out into the world. And photography is kind of different, where you’re looking around in the outside world to resonate with something that you respond to inside. Beautiful. That’s interesting. Now, I don’t see any art of your art on your walls, in your office there. so maybe for this interview, when we post it up, I’ll get picture of one of your pieces, and we can Because I would just love people to see the color and the design that you use in your art. I don’t know if it’s possible, probably not to post my art website, because that would be a good way for people to see my. We’ll figure it out. We’ll figure it out. So you went from visual art and you decided to write about your hearing loss. What prompted that? What prompted my book was I was at an age where I was kind of reflecting on the different influences in my life that have shaped who I am. And obviously, a severe hearing loss is a big impact. Who knows how my life would have unfolded if that had not been the case? But even more than that, I’m at an age where I had a lot of friends around me who are now getting hearing aids for the first time in their life due to usually mild age related hearing loss. And they are getting these fantastic, fabulous digital hearing aids. But they say to me, oh, now I know what it was like for you growing up with a hearing loss. And as sympathetic as I am to anybody dealing with hearing loss and hearing aids, that does take some getting used to. I know that they don’t know what it was like to have a severe to profound hearing loss from birth, not hearing a thing for the first four years, and then dealing with very primitive technology. People today take for granted the incredible digital hearing aids that they’re all wearing, which can do so much more than what I grew up with. so that’s really, I kind of wanted to really let people know what the range of impacts were. But your. Your book, from what I read, is so much more than that. It It’s. It’s about your life and your experiences, some of your travels. You lived in different countries. so as a person with hearing loss, I. Okay. Dealing with different accents, different languages. and. And your book is Did you live, you lived overseas? Not all that long. I lived for three years with my first husband in England. So they did speak English, although definitely with an accent. we lived in a very, very noisy apartment with the highway right outside the apartment, with the main road for trucks going to northern London. And there was a stoplight, and the brakes would come to a screeching halt at the truck stop. So I really struggled with hearing, even in our own apartment. And the classes that I was in was in large discussion group, classes that were difficult. I was on a kibbutz in Israel in between high school and college. And that was a very interesting time to be there, actually, given what’s going on now. But it was a very different, different time and experience. But the other volunteers that I worked with all spoke English. That was their common language. I tried to learn Hebrew, and it was hopeless. Too guttural in the back of the throat. I couldn’t lip read. and the same thing with German. I tried to learn the language of my parents, and I got to rudimentary German, but language is not my forte. Learning English was enough. Yeah, I get that. I actually have I was going to say an ear for languages. no longer, but without hearing loss, I think languages would have been a very important part of my life. I speak French to some degree, but again, it’s difficult now sometimes to understand and speech read English, let alone in a language other than my native tongue. but disappointment because I do, I do love languages. I love and it actually is interesting because I actually met a superb speech reader, as I’m sure you are, is that it takes no time at all. I’m watching a movie without sound on, which is something I often do, because noise bothers my tinnitus. But I can speech read accents. I can tell that someone is speaking English with, like, an english accent. Different types of english accents, french accents, Italian, because we’re used to speech formation, is different. So challenging to get to this point, but it’s fascinating. so you wrote the book. What was the process like writing that book? Well, at first, I did set out to write a full blown memoir. I just was writing memories, memories of growing up, memories of my relationship with my parents. I sprinkled my memoir throughout with interactions with my very complex and colorful father. At first it was in the form of poetry. And then I realized I’m not a poet. I have more to say. There’s just more that needs to be expressed. So I took some writing classes on the process of writing and creating scene and dialogue. And I had some wonderful teachers and classmates, and they at one point said, you know, you have enough material here for a full blown memoir, which was not what I had originally thought of. And so I wrote that and submitted it to a publisher, and it was picked up. So that was kind of like, wow, this is unexpected gift in my life. That’s wonderful. Did you Do you find writing difficult? No. The writing was the fun part. you know, it was fun. The crafting of writing, the editing of writing, playing around with words rewriting it, making it better each time. And of course, each time I look at the book, I say, oh, my God, I could. Could make it on another level. But at one point, I know this, like, within my painting also. You just have to, you know say, this is it as far as it’s going to go. Yeah, good for you. It’s with my writing through the years and before I started writing my books, I’ve written two. I don’t want to look at it after it’s published, because then I’ll find something. And you’re always going to look at it and say, oh, I could have said that better, or I should have perhaps shaded this differently. But I’ll tell you one scary thing that I hope and I’m sure won’t happen to you. In my first book called The Way I Hear it, A Life with Hearing Loss, published in 2015 which was my memoir slash survival guide. I call it I think it was only two years ago. I looked at. I was just looking through it. Sometimes I plagiarize myself from my weekly column, but I looked at a chart. There was just one chart in the book, and I went the charts backwards. It was all no one. The editor, the proofreader, my readers. so that was probably worst case scenario. So I will never, ever include another chart in a book again. So when it is published it was just published, right. maybe you might not want to read it for a while. Let others do the reading for you. so where can people get your book. Is it just online or is it in bookstores? It is in some bookstores. One can certainly order it through bookstore. I did get a starred review at library journals, so hopefully libraries will be carrying it or can order it. You can certainly order it through Amazon, Barnes and Noble, bookshop.org., you know, wherever you get books that should be very available. That’s great. That’s wonderful. there’s one other thing, Gael. I just want to mention that people ask me a lot because it is a through theme in my book, which is that I play a classical piano. I mean, we’re talking about different art forms and how that influenced my life. And my European parents were very into classical music, and I started taking lessons at age six. And then I played through high school and was getting quite good. And I really wanted to be a professional musician. But as I started accompanying other musicians, a cellist, a violinist, tried in an orchestra, I could not hear myself above the other instrument. I couldn’t distinguish the piano from the others. And so I realized that my first love and my first professional aspiration, I just could not do. And that was a kind of a painful letting go process. But people asked me, how were you able to hear with the piano? And the. The volume was not the issue. It’s more and it’s probably tuned ahead of time. so that was not the issue, as the volume was good. It was just later when I tried to play with other instruments that the discrimination issue. As you know, speech discrimination is also a big deal from background noise. I loved I don’t listen to music as much now, just the way my hearing has gone, unless I’m streaming. But I used to go to the symphony a lot, and I did have trouble discriminating certain instruments. but that’s why I love going to live symphony, because it’s like speech reading. I could see that there was percussion here, or this was a violin solo there and those sort of things. So it’s really. It’s like orchestra reading, I guess, instrument reading. But So I hope you still play for pleasure now, do you? I In my sixties, I had a friend who played the piano, and we did for him piano repertoire and gave some recitals at our house. And again, I did pretty well, not for perfectly, because I wouldn’t always, if she were playing the bass notes, I wouldn’t always discriminate my part from her bass notes, but I compensated by learning the notes really well and keeping time really well. So we did great. She, unfortunately, had moved away, so we don’t do that anymore. and so, yes, I sometimes play for my own pleasure, but at this point, writing is a solitary activity. Painting is a solitary activity. Piano playing is a solitary activity. And so I’m feeling, I want to be more engaged with the community, volunteering connections out there in the world. So we’ll see how that fits. You know, Claudia Marsielle I’m going to say I am in awe of your artistic soul and passion. I mean, you’re a writer and photographer and a painter, pianist. you’re probably a fabulous cook, too, you know. No, cooking is not my forte. You don’t cook. Oh. Anyway, it has been a pleasure, and I really encourage viewers to read your book and to share. I think it is so important to get the message out that hearing loss is not. Yes, it can be limiting, but we can go. We can break through those barriers, and we can expand our boundaries, and we can meet challenges. And so I just am so excited to welcome your memoir, your book, to the repertoire of fabulous stories of people who were walking in the same shoes with. So I wish you great luck. Hold that book cover up again, would you? Just? But you look so normal. Claudia Marseille, lost and found in a hearing world. Thank you so much for being with us in this weekend. Thank you, Gael. It was a delight to be with you. And as I said before, I so admire the work that you do and the advocacy that you do on behalf of those of us with hearing loss. It’s great. Thank you so much. Okay. And I look forward to meeting you in person one of these days. Yes, we will make that happen. Yeah. Thank you so much, Claudia. Thank you.

Be sure to subscribe to the TWIH YouTube channel for the latest episodes each week, and follow This Week in Hearing on LinkedIn and Twitter.

Prefer to listen on the go? Tune into the TWIH Podcast on your favorite podcast streaming service, including Apple, Spotify, Google and more.

About the Panel

Claudia Marseille was diagnosed with severe hearing loss at age 4. With determination and the help of powerful hearing aids, she learned to hear, speak, and lip-read, and was mainstreamed in public schools in Berkeley, CA. After working in challenging public policy jobs following graduate school, she sought a profession more compatible with her hearing loss and turned to her early love, the visual arts. Claudia’s strong visual sensibility, honed through reliance on sight, led her to earn master’s degrees in archaeology, public policy, and an MFA. She then developed a successful career in photography and painting, running a fine art portrait photography studio for fifteen years before becoming a full-time painter.

Claudia Marseille was diagnosed with severe hearing loss at age 4. With determination and the help of powerful hearing aids, she learned to hear, speak, and lip-read, and was mainstreamed in public schools in Berkeley, CA. After working in challenging public policy jobs following graduate school, she sought a profession more compatible with her hearing loss and turned to her early love, the visual arts. Claudia’s strong visual sensibility, honed through reliance on sight, led her to earn master’s degrees in archaeology, public policy, and an MFA. She then developed a successful career in photography and painting, running a fine art portrait photography studio for fifteen years before becoming a full-time painter.

Gael Hannan is a writer, speaker and advocate on hearing loss issues. In addition to her weekly blog The Better Hearing Consumer, which has an international following, Gael wrote the acclaimed book “The Way I Hear It: A Life with Hearing Loss“. She is regularly invited to present her uniquely humorous and insightful work to appreciative audiences around the world. Gael has received many awards for her work, which includes advocacy for a more inclusive society for people with hearing loss. She lives with her husband on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada.

Gael Hannan is a writer, speaker and advocate on hearing loss issues. In addition to her weekly blog The Better Hearing Consumer, which has an international following, Gael wrote the acclaimed book “The Way I Hear It: A Life with Hearing Loss“. She is regularly invited to present her uniquely humorous and insightful work to appreciative audiences around the world. Gael has received many awards for her work, which includes advocacy for a more inclusive society for people with hearing loss. She lives with her husband on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada.