J. Donald Harris, Ph.D.

Michael Spelman, Cal Poly Bio 502, Feb. 24, 2014

Many years ago I purchased a small book titled “Some Relations Between Vision and Audition” by J. Donald Harris. It was published in 1950, and I purchased it at the publisher’s year-end book sale, where they were attempting to empty their stock of no longer moving product. I recall that I paid $1.00 for the book (which is why I purchased it because I could just afford that price), which now has to be a collector’s item, although most likely only for nerds having an interest in hearing. Most fascinating to me was Dr. Harris’ insight into basic relations between vision and audition, and his ability to formulate those relations. Today, some of the questions posed by Dr. Harris have been answered. Still, his descriptions bear reviewing, if for no other reason but that he showed great vision (no pun intended) in discussing these two senses. Much of what follows is taken directly, and only from this booklet. As such, no attempt was made to cite each reference from the booklet.

J. Donald Harris, Ph.D., was Head, Sound Section, U.S. Naval Medical Research Laboratory, New London, Connecticut. And, I might mention, one of the best presenters I ever listened to. The book (because it consisted of only 56 pages, I will call it a booklet) was actually Publication Number 71, American Lecture Series, a Monograph in American Lectures in Otolaryngology. Why this was published as a separate book remains a mystery.

Human Senses

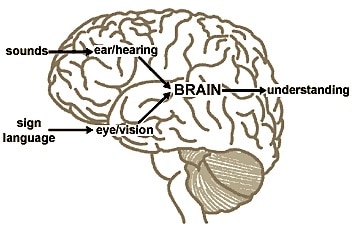

The human senses are: hearing, sight, smell, touch, and taste. Among the five human senses, vision and hearing are considered the most sophisticated due to their substantial representation within the cortical regions of the central nervous system (CNS). Interestingly, vision and hearing fail more frequently and more rapidly than do taste, touch, or smell.

The human senses are: hearing, sight, smell, touch, and taste. Among the five human senses, vision and hearing are considered the most sophisticated due to their substantial representation within the cortical regions of the central nervous system (CNS). Interestingly, vision and hearing fail more frequently and more rapidly than do taste, touch, or smell.

What Do The Eyes and Ears Have in Common?

At first glance, one might think they have nothing in common except that both are placed on the head, thus serving along with the nose to alleviate the monotony of an otherwise unrelieved spheroid. Differences are more numerous than similarities. For example, the two organs derive from different primitive germ layers, and handle very different spectra.

On the other hand, the similarities between audition and vision are often striking. Both organs serve to collect and sort stimuli impinging on the organism. Thanks partly to the organization of the two sensory systems, these essentially random stimuli are given spatial and temporal organization and become for us the basis for our meaningful experimental world.

Temporal and Spatial Organization

Consider the confusion in our perceptual world if our eyes retained, for much longer durations than they do, impressions of objects that had passed beyond our field of vision. Or, consider what our auditory world would be if the ear were so built that it resonated for several seconds to frequencies commonly found in human speech, instead of damping almost immediately as it does within the entire audible range. There are many correspondences in the ways these two organs have developed for maximum biological efficiency. Both have developed the capacity to respond to stimuli so weak that the limiting value is imposed almost as much by the nature of the physical stimulus as by the nature of the end organ. They have also developed the capacity to respond to intensities so great that other tissues of the body beside the receptor surfaces are likewise threatened. Their ability to respond differentially to two stimuli is likewise on a very high level of efficiency.

Other Instructive Parallels

Many instructive parallels between vision and audition can also be drawn. For example, the problem of constructing scales of psychological magnitudes (such as brightness of lights or pitch of tones, as distinct from physical magnitudes such as intensity or frequency) cuts across sensory distinctions in attempts to find anchors or zero points on a psychological continuum and attempts to find yardsticks to lay along such a continuum.

Other examples could be the quantum theory of light that has led to attempts to apply such thinking to audition. Or, the interchange of information now possible as a result of using micro-stimulation and micro-electrode techniques in the retina and also in the auditory nerve.

Harris believed that it is only by abstracting and comparing what we know of the sensory-neural activities of all the senses that we can move toward arriving at general principles of organization and theory of the whole sensorium.

Sensitivity Comparison

How efficiently do the eye and ear collect the facts of the physical world and transduce them into sensation?

It is significant to note that neither organ produces zero sensation if a stimulus intensity of zero is applied. The eye does not report “black” to the brain if there is no external stimulus, but an idioretinal grey instead. Likewise, the ear manufactures its own slight sound level. This is easily demonstrated in an anechoic room. An initial sensation is a change in barometric pressure, with other “noises” following, such as the beating of the pulse in the external auditory canal, then very weak but steady sound of wide frequency spectrum caused by slight mandibular movements amplified and resonated in the ear canal, or perhaps by imbalances of the mechanical auditory system proper. It is, then, over these backgrounds that external signals must make themselves known.

Do the “ayes” or the “ers” have it?

It is customary to regard the eye as far superior to the ear in terms of physical energy transduced. Radiant energy, one would think, is on a different, less powerful, level than air waves, the latter of which may be so strong as to be sensed by the skin. This would imply that the eye has to work harder to pick up and transduce the less intense overall physical radiant energy.

But, as an ear professional, it is recognized that the eardrum has to move in and out only to the distance of 0.1 the diameter of a hydrogen molecule (.000,000,01 mm) before a sound is heard. Further, the basilar membrane then only has to undergo an excursion of 0.1 that at the eardrum. It is clear that a very slight amount of energy can cause these minute amplitudes, and we should not be surprised if the ear compares favorably with the eye in this matter.

The fact is that in terms of energy at threshold, in spectral regions where the two organs are most efficient, the eye and ear are roughly similar. Vision requires 2.2 to 5.7 x 10-10 ergs, and audition requires about 1 x 10-9 ergs per second. These values are approximately the weight of a mosquito’s wing, dead or alive. (I did not realize that they had trivia questions back in the 1950s).

What is interesting is that in both organs, sensitivity is almost at theoretical limits. For the eye, in the scoptic region, the amount of energy needed to stimulate is very close to the magnitude of the ultimate radiation quantum (Hecht). Here, any further increase in sensitivity would be biologically useless. For the ear, between 1000 and 3000 Hz, the amount of energy needed to stimulate is very close to the energy of the noise produced by collision of air molecules in random Brownian movement.

If the ear had a marked increase in sensitivity, it could possibly result in a more noticeable intra-aural noise, together with the masking produced by that noise. For example, for those whose ears that have great sensitivity (say, 15 dB better than “normal), such a condition may occur. Fifteen dB can be interpreted as an energy ratio of a little more than 1:5, meaning that the average hearing person can only just detect a sound that contains five times the energy of a sound that a particularly sensitive person can detect. Perhaps they can hear Brownian movement, but then interpret it as the same endaural noise that all average persons describe.

“In terms of energy at threshold, the eye and ear are roughly similar. Both organs operate close to their theoretical limits of sensitivity. Any further increase in sensitivity could result in biologically useless effects or an increase in intra-aural noise for the ear.”

How do these 1950s statements compare with more recent data?

A 2013 study that investigated vision versus hearing comparisons of sensitivity and audibility functions, implied that human adults showed a relationship between threshold levels of hearing and vision, at least in terms of the overall stimulus area defined by the contrast sensitivity (CS) and audibility functions. This finding suggests that for individual adults, there is some commonality in basic functioning between the two sensory systems within the human CNS.

Harris made other comparisons between vision and audition. These included wave length, energy integration, growth and decay of sensation, bilateral interaction, peripheral and central explanations of acuity, the quantum theory of threshold and of discrimination, and intersensory facilitation. I will attempt to provide information on these in some future posts.

Reference:

- Sivian, L.J., and White, S.D. On minimum audible sound fields. J. Acous. Soc. Amer. 4:288-321, 1933

- Adams, R.J., Sheppard, P., Cheema, A., and Mercer, M.E. Vision vs hearing: direct comparison of the human contrast sensitivity and audibility functions, Meeting abstract presented at VSS 2013, received June 26, 2013

Wayne Staab, PhD, is an internationally recognized authority in hearing aids. As President of Dr. Wayne J. Staab and Associates, he is engaged in consulting, research, development, manufacturing, education, and marketing projects related to hearing. His professional career has included University teaching, hearing clinic work, hearing aid company management and sales, and extensive work with engineering in developing and bringing new technology and products to the discipline of hearing. This varied background allows him to couple manufacturing and business with the science of acoustics to bring innovative developments and insights to our discipline. Dr. Staab has authored numerous books, chapters, and articles related to hearing aids and their fitting, and is an internationally-requested presenter. He is a past President and past Executive Director of the American Auditory Society and a retired Fellow of the International Collegium of Rehabilitative Audiology.

**this piece has been updated for clarity. It originally published on June 4, 2014

Hello Wayne,

Very interesting article. I remember J Donald Harris very well. He lectured at the City University once a week.. He would drive down from the Naval Base at Groton, Connecticut at breakneck speed and never got a ticket.

He was a very interesting person with interesting ideas.

Harry

Harry:

He was definitely interesting and was a great wordsmith. He was also unique in that, to the best of my knowledge, is the only person who had his own journal, “The Journal of Auditory Research.”