Although hearing aids during the past several years have mostly been devoid of a user-adjustable volume control (VC), this feature has been requested by some individuals fitting WDRC (Wide Dynamic Range Compression) hearing aids and by many consumers. As suggested in a previous post, no single volume control setting is ideal for a hearing aid wearer under all conditions, even if the hearing aid volume control level changes with different programming amplification options.

Although hearing aids during the past several years have mostly been devoid of a user-adjustable volume control (VC), this feature has been requested by some individuals fitting WDRC (Wide Dynamic Range Compression) hearing aids and by many consumers. As suggested in a previous post, no single volume control setting is ideal for a hearing aid wearer under all conditions, even if the hearing aid volume control level changes with different programming amplification options.

Last week’s post described in part the status and explanations as to why most hearing aids do not have user-adjustable volume controls. That post surmised that fewer than 45% of hearing aids have such a control, and suggested that the percentage might be even substantially lower if behind-the-ear RIA (receiver-in-aid) instruments were included. No current statistics were found on this issue.

User Control of Volume

User Control of Volume

This post will further explore the issue of user-control of volume, based on studies that have investigated this issue. What readers will find is that such studies are minimal, and often do not address the issue in an easily comparative manner.

Ideally, armchair logic would tend to suggest that hearing aids should be so intelligent in responding to environmental listening conditions that no adjustment would be necessary. However, based on studies and reports, this is not likely to be the case because of differing individual preferences for desired listening levels at a given time.

This premise is supported by MarkeTrak VI{{1}}[[1]]Kochkin, S. Isolating the impact of the volume control on customer satisfaction, 2003, The Hearing Review, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp 26-35[[1]] which showed that only 42% of hearing aid wearers were satisfied with their hearing aid’s loudness comfort. What is more significant is that this means that 58% are not satisfied with their hearing aid’s loudness comfort. This alone would tend to suggest the desirability of a user-adjustable volume control.

Do Hearing Aid Wearers Prefer a Self-Adjusted Volume Control?

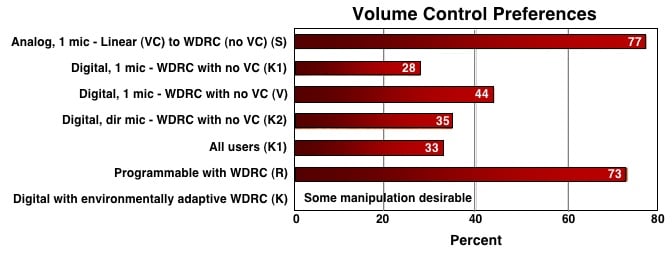

Valente et al. (1998){{2}}[[2]]Valente M, Fabry DA, Potts LG, Sandlin RE. Comparing the performance of the Widex SENSO digital hearing aid with analog hearing aids. J. Am Acad. Audiol. 1998:9(5);342-360[[2]]. The authors reported that 44% of experienced hearing aid wearers found the absence of a volume control as “somewhat or very unappealing.”

Kochkin (2000){{3}}[[3]]Kochkin, S. Customer satisfaction with single and multiple microphone digital hearing aids. Hearing Review, 2000: 7(11):24-34[[3]]. He reported that when using a single-microphone hearing aid having WDRC performance and no volume control, 28% of users preferred a control. For multiple-microphone hearing aids, 35% preferred a volume control. (This may not be surprising because a multiple-microphone hearing aid [directional hearing aid], when activated, generally reduces some of the low-frequency amplification, making the overall amplification somewhat softer). However, those who did not desire a volume control reported higher satisfaction ratings than those who preferred a control (81% vs. 42%).

Surr et al. (2001){{4}}[[4]]Surr, RK, Cord, MT, and Walden, BE. Response of hearing aid wearers to the absence of a user-operated volume control, (2001). The Hearing Journal, Vol. 54, No. 4, pp 32, 33-34, 36[[4]]. These researchers found that 77.2% of experienced/satisfied users prefer a volume control, regardless of how advanced the “automatic” technology used in their hearing aids. The automatic technology was a two-channel WDRC hearing aid. These results were based on early hearing aids that were not generally as sophisticated as today’s, but the fact that these were experienced users makes the study worthy of consideration. It is important to know also that the study was based on all subjects having previously worn linear hearing aids with user-adjustable volume controls.

Adaptive Hearing Aids to the Rescue?

Although the previous studies have reported that a significant number of hearing aid wearers would prefer user-adjustable volume controls, they have not been available with most digital hearing aids. The study by Surr et al. (2001) indicated that the WDRC function alone seems not to be the answer. However, with later digital hearing aids using WDRC function in different programmed environmental settings, where the algorithm calls for modified performances, each with programmed adaptive gain, might a user-adjustable volume control be necessary?

Adaptive hearing aids currently refer to those that automatically change their signal processing (gain, frequency response, directional performance, etc.) in response to changes in the input signal. The changes are programmed into hearing aids. These are identified as preferences for different listening environments (noise, quiet, music, restaurant, etc.), and are user selectable with a push button on the aid.

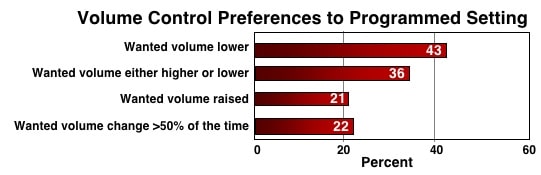

Rhys (2006){{5}}[[5]]Rhys, M. Volume control preferences with WDRC digital hearing aids, 2006, The Hearing Review, July 24, 2006[[5]]. This appears to be the first study investigating user preference of a WDRC digital hearing aid with a manual control activated or deactivated. Of 28 participants, 73.7% chose to have the manual volume control activated, and 26.3% chose to have it deactivated.

Keidser (2009{{6}}[[6]]Keidser, G. Many factors are involved in optimizing environmentally adaptive hearing aids. (2009). The Hearing Journal, Vol. 62, No. 1, pp 26, 28, 29-31[[6]]. To determine how adaptive hearing aids were being used, Keidser collected data from 606 subjects who were wearing environmentally adaptive hearing aids. This was done in response to other studies showing that some hearing aid users do not use these alternate programs much of the time. Her overall results suggested that some individual manipulation of the volume control is desirable, even in an environmentally adaptive hearing aid. Or, if not that, then individual training in the use of an adaptive hearing aid is required, especially of the overall gain.

As an aside, it is this writer’s observations that when hearing aids are programmed to various environmental settings established by the manufacturer, users often have a difficult time hearing the differences, other than changes in gain associated with the listening environments. When moving to a different environment selection, many users will comment that they can no longer hear as well – generally meaning that the gain is insufficient.

Trying to Make Sense From the Numbers

Trying to Make Sense From the Numbers

Comparing the existing studies related to volume controls does not provide an apples-to-apples comparison. The reason for this is that depending on the years they were conducted, the five major referenced works involved differing hearing instrument technologies. This means that the gain functions in the subject studies all involved different electronics, algorithms, and microphone arrangements (single or multiple) for managing gain.

The Valente et al. (1998) study involved a radical departure in hearing aid design – from a manual volume control to none. In the case of Surr et al. (2001), the study was conducted during a transition from linear or conventional AGC (automatic gain control) instruments to WDRC. The study by Rhys in 2006 compared WDRC hearing aids with linear hearing aids. This was followed up with observations from Keidser (2009), in which questions were asked about adaptive hearing aids with WDRC and multiple selectable listening programs, all of which are assumed to have had different gain settings with each program. Data reported from MarkeTrak Reports blanketed all of these.

Attempting to determine the need for a manual volume control in hearing aids based on these studies is akin to solving the mystery of the pyramids. Reports related to volume controls have no consistent populations for comparison and they describe volume control desirability in different ways (satisfaction, preference, use, adjustment, date of the study, types of hearing aids worn, intended use of the hearing aid, algorithms used, number of microphones, etc.). As a result, direct comparison between the studies evolves into an exercise in futility.

With this in mind, following are some overall observations

Prefer VC

Key: S – Surr et al 2001; K1 – Kochkin 2000; V- Valente et al 1998; K2 – Kochkin 2003; R – Rhys 2006; K- Keidser 2009

Key: S – Surr et al 2001; K1 – Kochkin 2000; V- Valente et al 1998; K2 – Kochkin 2003; R – Rhys 2006; K- Keidser 2009

VC highly desirable feature = 78% in U.S. (Kochkin, 2003)

Prefer Easier VC Adjustment (Kochkin, 2003)

United States = 72%

Germany = 65%

Prefer Higher or Lower Gain Than Programming Software (Surr et al., 2001)

Long-time wearers trended toward higher gain than those with less HA experience

Satisfaction RATING With Loudness Comfort (this is a rating %, not % of subjects)

No VC preferred = 81% (Kochkin, 2000)

VC preferred = 42% (Kochkin, 2000)

Satisfaction Based on Hearing Aid Wearing Experience and VC

Experienced wearers = More satisfied (Surr et al., 2001)

Experienced wearers = 56% preferred VC (Valente et al., 1998)

Experienced wearers = 88.9% preferred VC (Rhys, 2006)

New wearers = 60% preferred VC (Rhys, 2006)

New wearers (Surr et al., 2001) = Satisfaction increased if had automatic gain

Hearing Aid Volume Control and User Satisfaction

Kochkin (2003) offers the following thoughts, from dispensers and consumers, as to volume control desirability and user satisfaction:

- Experienced hearing aid users are less likely to give up the manual VC.

- Differences reported between new and experienced user satisfaction with hearing aids may have nothing to do with the VC, but instead, the absence may represent a “scapegoat,” in that a VC could have prevented dissatisfaction with the hearing aids.

- Automatic adaptive hearing aid features work well, but not in 100% of listening situations. A manual VC override allows consumers to more finely “tune” their hearing aid to their preferred volume listening level. This is in response to the report that only 42% are satisfied with loudness comfort in their current hearing aids.

- Some hearing aid wearers must psychologically be in control of their aid and not a prisoner to the signal processing strategy and its automatic control.

- Long-term hearing aid wearers are used to a VC and unwilling to part with it through habit.

Volume Control or Not?

The overall consensus appears to be an emphatic “yes,” at least as a ready and available option. It may not matter so much how it is done (remote or on device), but that it is available to assist, if even in a small way, to improving hearing aid user success.

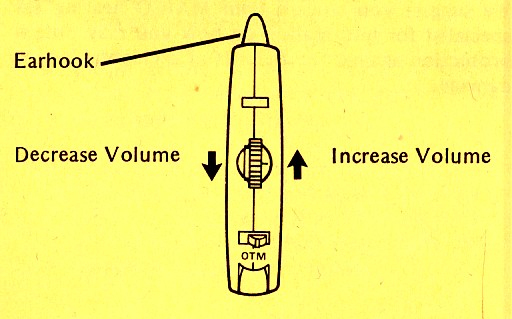

Next week’s post will discuss directions to manage volume controls in hearing aids, along with some hearing aid wearer comments about the need for such control.

Good topic Wayne -and good article, and a chance for me to mutter about one of my concerns about the hearing aid literature. Despite all the millions that go into hearing aid research, and despite the huge price differentials between hearing aid models, most of the hearing aid literature treats hearing aids as though they all perform the same. No wonder the public is confused. The interaction between personal preferences, types of features and types of amplification is rarely studied and reported. A clinician will make a judgement based around what they know about a particular hearing aid, and around the clients preferences. I was reminded of a designer, specializing in chairs for people with severe arthritis, saying to a researcher: ” I’m not interested in making “the average chair”, based on averaged results, I want to know the individuals in your trial”. So, the path Blamey and Saunders have taken is adaptive, with volume control.

Thank you Wayne for raising the volume e control issue and to Elaine for noting the widespread consumer confusion. I’m a consumer. I have a volume control on my cochlear implant, but not on my costly, branded BTE hearing aid. I’ve often asked myself “why?” The only answer I come up with that makes sense to me is that the manufacturers don’t want to give away something they can profit from by selling: namely a remote control volume device. I bought one – and very much regret it, not because volume control isn’t useful to me, but because I dislike having to carry around another device.

It’s the same with virtually all assistive listening devices. Each manufacturer makes products (FM, direct connects, t-coil streamers, etc.) that are proprietary and only work with their hearing aids.

I tend to think Jerry, above, has a good point. Selling peripherals is a vital part of the business model. I paid $150 for a remote volume control (talk about klunky) only to find out, on my own, that each of my two aids could control a separate array of features. So my left aid button controls the volume for both aids, and my right aid controls the program (again, for both).