From “Going Deep” to the CIC (completely-in-canal) Hearing Aid

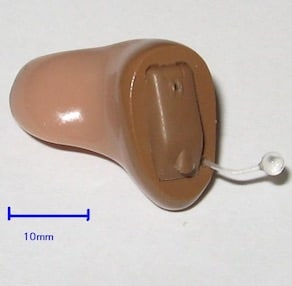

Hearing aids are available in a wide variety of sizes, configurations, and styles. Styles include BTE (behind-the-ear), RIC/RITE (receiver-in-canal/receiver-in-the-ear), thin tube, ITE (in-the-ear), ITC (in-the-canal), CIC (completely-in-canal), IIE (invisible-in-ear), and other variations. While all seem to have their place in the fitting process, it is undeniable that a major driving force for hearing aid design and sales has been, and continues to be, that of cosmetics.

This post focuses on the historical origin of the CIC instrument. The reason for this is because it, and developments leading up to it, created an important background to hearing aid design and use. It wasn’t only the production of making something smaller, but related also to acoustical modeling of miniaturized hearing aids.

Following the Paper Trail

The trail reflecting the path to the CIC instrument is detailed in reviewing the literature, and is enhanced further when direct, personal contribution and knowledge is provided, with the author having been an active participant. So, let’s follow the paper trail.

The Occlusion Effect and Deep Fitting Canal Hearing Aids

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, a series of events occurred that brought a specific hearing aid fitting issue to the radar screen – the occlusion effect. Briefly, the occlusion effect is a hearing impaired person’s complaint that their own voice sounds “hollow,” “booming,” or “echoing” when they speak while wearing their hearing aids. This has been a major complaint since electronic hearing aids were first worn.

A movement to try to eliminate the occlusion effect was generated by an article written in 1988 by Killion, Wilber, and Gudmundsen{{1}}[[1]]Killion, M., Wilber, L., and Gudmundsen, G. Zwislocki was right, Hearing Instruments, 1:14-18, 1988[[1]].  They reported that a canal hearing aid that made contact with the bony portion of the ear canal could reduce the occlusion effect significantly. This was something that Zwislocki had alluded to in a 1953 article{{2}}[[2]]Zwislocki, J. Acoustic attenuation between the ears, J. Acous. Soc. Amer. 25.752-759, 1953[[2]] unrelated to the actual fitting of hearing aids, but related to intra-aural attenuation. This writer experienced a similar impact on the occlusion effect in the mid 1980s with the introduction of a very small stock canal hearing instrument that terminated more deeply into the ear canal, and that was not vented{{3}}[[3]]Staab, W.J., Stock ITCs: a new fitting and marketing philosophy. Hearing Instruments, 1:24, 1985[[3]]. However, at that time, hearing aid product development was heavily focused on cosmetics (smaller size), comfort, and ease of fit, and that drove the market, perhaps even more than patient sound quality needs.

They reported that a canal hearing aid that made contact with the bony portion of the ear canal could reduce the occlusion effect significantly. This was something that Zwislocki had alluded to in a 1953 article{{2}}[[2]]Zwislocki, J. Acoustic attenuation between the ears, J. Acous. Soc. Amer. 25.752-759, 1953[[2]] unrelated to the actual fitting of hearing aids, but related to intra-aural attenuation. This writer experienced a similar impact on the occlusion effect in the mid 1980s with the introduction of a very small stock canal hearing instrument that terminated more deeply into the ear canal, and that was not vented{{3}}[[3]]Staab, W.J., Stock ITCs: a new fitting and marketing philosophy. Hearing Instruments, 1:24, 1985[[3]]. However, at that time, hearing aid product development was heavily focused on cosmetics (smaller size), comfort, and ease of fit, and that drove the market, perhaps even more than patient sound quality needs.

Similar observations to those of Zwislocki had been made by other researchers{{4}}[[4]]Khanna, S.M., Tonndorf, J., and Queller, J. Mechanical parameters of hearing by bone conduction. J. Acous. Soc. Amer. 60:139-154, 1976[[4]],{{5}}[[5]]Berger, E.H., and Kerivan, J.E. Influence of physiological noise and the occlusion effect on the measurement of real ear attenuation at threshold. J. Acous. Soc. Amer. 74:81-94, 1983[[5]], but these were unrelated to hearing aids, and therefore had essentially no impact on hearing aid design and/or use at the time.

Directed Involvement with Deep Canal Hearing Aids and the Occlusion Effect

In 1988, a hearing aid dispenser in Las Vegas, NV, Barry Finlay{{6}}[[6]]Finlay, B. Personal communication and data collection, Las Vegas, NV, December, 1988[[6]] encouraged this writer (in my position as Dahlberg/Miracle-Ear VP Professional Services) to work with him to have ITC hearing aids manufactured that made contact with the ear canal’s bony structure. This was intended to eliminate the occlusion effect following the writings of Killion, et. al. (1988).

Results with hearing aid bony section contact were excellent in the elimination/reduction of the occlusion effect, along with other favorable customer reactions. After a little over two years of experience in fitting hundreds of patients, learning how to take deeper ear impressions, determining the ITC fabrication methods required, customer interviews, and data collection, the first systematic fitting rationale and procedure for deep canal ITC hearing aids was published{{7}}[[7]]Staab, W.J., and Finlay, B. A fitting rationale for deep fitting canal hearing instruments, Hearing Instruments, Vol. 42, No. 1, pp 6, 8, 10, 48, 1991[[7]].

Labeling hearing aids that fit deeply into the ear canal as something other than “deep canal hearing aid fittings,” resulted in the term “peritympanic,” first used in the literature in 1990{{8}}[[8]]Orchik, D, Gowgill, S., and Parmely, J. Peritympanic soft hearing instrument fitting in high frequency hearing loss. Hearing Instruments, Vol. 41, No. 11, 1991[[8]]. This term was used in reporting on three cases fitted with modular/stock, soft canal instruments made by Bausch & Lomb. The intended definition of “peritympanic” was to convey an instrument that terminated in close proximity to the tympanic membrane{{9}}[[9]]Orchik, D. Personal communication, Shea Otologic Clinic , Memphis, TN., September, 1988[[9]].

That deep canal hearing aids could be evaluated easily using probe microphone real ear measurements was reported in 1991{{10}}[[10]]Northern, J., Jennings Kepler, L., and Abbott Gabbard, J. Deep canal fittings and real ear measurements, Hearing Instruments, Vol. 42, No. 9, 1991[[10]]. In the same year, Bryant et al{{11}}[[11]]Bryant, MP., Mueller, HG, and Northern, JL , Minimal contact long canal ITE hearing instruments. Hearing Instruments, 1:12, 1991[[11]] reported that deep canal modified technology using minimal contact in the cartilaginous portion of the ear canal, but making contact more deeply in the bony canal, produced greater high frequency gain at 4000 Hz. Additionally, five of eight subjects reported less occlusion effect and improved speech discrimination.

These first published reports related to deep canal fittings were intended primarily to support one of two purposes: 1) to overcome the dreaded occlusion effect that hearing aid wearers were experiencing with hearing aids that terminated shallowly in the cartilaginous portion of the ear canal, or, 2) to confirm that the deeper fit produced increased high-frequency response when measured via real ear probe microphone and/or through functional gain.

Next weeks post will continue this historical development: XP to the CIC.

“Minimal contact long anal ITE hearing instruments.”

Might want to fix that typo, although I know we’re all getting a kick out of it!

Joe: Thank you very much for catching that. You are much better than spell check, although I should know how to spell canal. I don’t believe that we have yet progressed that far in fitting hearing aids.