First Rule of Thumb

A patient will prefer the hearing aid that provides amplification at the level they desire. This is axiomatic regardless of any acoustic frequency response modifications that might be available.

This hearing aid user listening level acceptance may or may not be the level that the fitter or programming formula designates. Even if they agree, it is not a guarantee of goodness of fit.

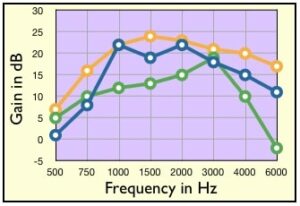

For example, comparing target gains by three major manufacturers for the same, typical hearing loss, with each manufacturer using their proprietary “first fit” formula, shows that they do not recommend the same amount of gain. As much as a 10-dB difference exists in the target gains at 1000 Hz (discounting 6000 Hz, where the difference is even greater). Add to this the ±5 dB variability of traditional hearing testing increments, and the differences can easily exceed 15 dB. Adding target gains from an expanded group of manufacturers is likely to provide additional target gains.

Is this difference meaningful? Can a patient hear this difference? For a normal listening individual, 10 dB is approximately equal to a doubling of loudness, and perhaps even greater for a person with a hearing loss, due to the non-linearity of the ear. So, the answer to both questions is “yes.”

Figure 1. Target gains of “first fit” programming for three different hearing aid manufacturers, each using their proprietary programming.

So, which of the three levels in Figure 1 is correct? That is the unknown. It is common to explain these differences away by saying that these are just “starting gain suggestions” and that further adjustments will be made. Unfortunately, much “first fit,” or what some call “quick fit,” programming is what the patient often leaves the office with. Return visits are generally scheduled to modify gain and/or feedback performance.

While it is true that adjustments can be made during the fitting, or even post-fitting, how does the hearing aid know what level is most desirable for the user in different listening environments, even after adjustment? After all, adjustment of the loudness level in a dispenser’s office is not likely to suit the customer’s personal and changing listening environments. Likewise, there is no evidence that a person’s listening preference levels remain constant throughout the day, or even from day to day. It is assumed to be dynamic. As a result, leaving with the in-office re-adjustment is still no guarantee that the listening level is correct.

What Have the Options Been?

Recent traditional options to manage the loudness volume levels include:

- A variety of pre-set hearing aid programs (accessed by push button by the user) for different listening environments, each with different gain, and other, settings,

- Adaptive gain control of the hearing aid, based on input signal spectrum, timing, and levels – automatic gain control allowing no user-adjustment,

- Remote controls to adjust loudness

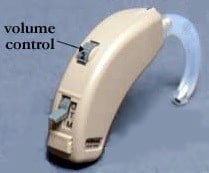

- User-adjusted volume control (VC) on the hearing aid

The issue that determines the most appropriate option relates to user experience. If the pre-programmed settings or adaptive gain are acceptable, these are excellent choices. If, on the other hand, a user desires more or less gain in a given situation, he/she does not ordinarily have the option of “overriding” the setting programmed into the hearing aid.

Hearing Aid Volume Control History

Yes, Dorothy, at one time all hearing aids had a user-adjustable volume control. Can you imagine that?

As late as 1994, Kochkin{{1}}[[1]] Kochkin, S. (2003). Isolating the impact of the volume control in customer satisfaction, The Hearing Review, January, pp 1-6[[1]] reported that 98% of the hearing aids had a volume control. By 2012 that number was estimated to be approximately 40% based on the HIA Quarterly Report stating that 45.62% of the BTE hearing aids had an external speaker{{2}}[[2]]Hearing Industries Association Statistical Reporting Program, 4th Quarter, 2012[[2]]. These comprised essentially digital hearing aids designed with programmable environmental settings, which did not include volume controls. A few percentage points can be deducted for some custom-molded hearing aids without volume controls. It does not include open thin-tube behind-the-ear hearing aids, many of which had no volume control, meaning that the percentage could be substantially less than estimated.

The Disappearing Volume Control

What led to the dramatic reduction of volume controls on hearing aids? The events could be categorized as follows:

1. Space and/or malfunction. Hearing aid development has a history directly related to cosmetics. The request for smaller and less conspicuous hearing aids continues to this date. Making the hearing aid smaller by omitting certain features has always been an option. With volume controls, the direction was to make them smaller, or in some cases, to eliminate them. This was especially true with custom-molded hearing aids. For years, volume controls were the number one repair problem, primarily related to their mechanical function. As a result, some developments occurred to circumvent mechanical breakdown problems.

Ensoniq (1989). Among the first to advocate for volume control removal was a product called the Ensoniq Sound Selector{{3}}[[3]]Sound Selector: high resolution listening instrument and fitting system, Ensoniq, Preliminary technical sheet, August 8, 1989[[3]]. This was a 13-band high-resolution hearing aid that provided “freedom from volume control correction.” The manufacturer stated:

The key is a properly balanced frequency response that is smooth. By amplifying each frequency in the right proportion and smoothing the response, we increase the client’s dynamic range that keeps them from having to constantly adjust the volume to stay within the desired range. This is another benefit of a transparent fit.

As a result, Ensoniq decided to design their hearing aids without a VC (volume control), following first run products. This was a case where the design engineer/owner found that he did not need a VC on the hearing aid he wore, so it was deemed that a VC was unnecessary for everyone, and designed out of the hearing aid.

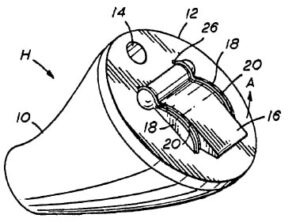

Figure 2. Touch volume control of the Richards hearing aid. A finger touch to the raised element of the hearing aid faceplate put the fingers in contact with the touch terminals (20). Touching and holding raised and/or lowered the hearing aid volume to the desired level.

Richards Medical Company (1988). Richards designed “touch contacts” that provided user-control of volume, but without any external mechanical VC{{4}}[[4]]Touch contacts for hearing aid volume control. (5/19/88). European Patent 0 311 233 A2, Application Number: 88304536.1[[4]]. The design replaced the variable resistor of then current hearing aids with a hearing aid circuit requiring the use of only two touch sensitive contacts on the hearing aid surface, identified as number 20 (Figure 2). Touching the two contacts a first time and holding the contacts increased the volume, while touching the contacts a second time and holding the contacts resulted in a reduction in the volume of the hearing aid. The contacts were easy to locate because they were a part of the only raised element of the hearing aid. The touch terminals were connected to a controlled resistance internal to a transconductance block in the hearing aid. Touching the contacts varied and alternated the resistance developed between the touch terminal wires 20.

2. Digital Technology, Multiple Memories, and WDRC. Following the development of programmable analog, and then digital hearing aids, the fitting emphasis was on providing a selection of hearing aid performance options to coincide with different environmental listening situations (quiet, noise, music, etc.).

With the ability to program several different environmental listening settings into hearing aids, the external user volume control that had been a staple of hearing aids for decades was essentially set aside. The “control” that would have been used for volume was essentially replaced with a push-button option to change response settings, each generally having a different gain level to coincide with the expected amplification need for that environment.

Additionally, the hearing aids were programmed with built-in adaptive gain, wherein the gain of the instrument varied depending on the level of the incoming signal. If the input signal was soft, greater gain was called for, and if the signal was loud, less gain was called for. This, in itself, was not new to hearing aids, but benefited from two previous major developments.

The first, that of Automatic Volume Control (AVC) circuitry, had been a feature of hearing aids for decades before digital hearing aids, but was now better controlled because of digital technology. The AVC utilization was improved greatly by the introduction of a second major development that reversed traditional amplification action – WDRC (Wide Dynamic Range Compression). This signal processing development{{5}}[[5]]Killion, M. (1988). An “acoustically invisible” hearing aid, Hearing Instruments, Vol. 39, pp 40-44[[5]] provided greater amplification for soft input signals and less gain as the input signal increased.

With WDRC providing comfortable amplified listening levels regardless of the loudness of the source, and coupled with user-selected environmental settings, the external volume control fell by the wayside, especially for advanced performance hearing aids. This development trend away from user-adjustable volume controls in such hearing aids continued during the past two decades. As a marketing tool, having no VC was good because it removed the stigma and action of having to adjust the volume control manually as the environmental sounds changed in loudness, and mechanical volume control problems were eliminated.

3. Ease of HA Use and Stigma Reduction. Moving the hand to the ear to change the VC was an inconvenience for some hearing aid users, especially if the VC had to be changed often. Additionally, the action called attention to the wearer when making adjustments. While it is true that moving the hand to the ear to change environmental listening programs on current digital hearing aids is required (unless one has a remote-controlled device), the number of times this action would occur is substantially less. Regardless, the adaptive gain feature made it much easier for hearing impaired individuals to wear hearing aids with greater ease.

Next week’s post will highlight studies related to volume control use.

One overlooked issue with the diminishing volume control, is the option of the user to couple their device with assistive technologies; in particular, hearing loops. FM and infrared both require receivers that can manipulate the volume; loops do not have that advantage. With the current interest in hearing loops, it is pertinent for those who fit and sell hearing instruments, to explain to clients the trade off they are making when they agree to purchase a hearing instrument sans VC. Hearing Loops are being installed all over the country. Sadly, many who use the very tiny new BTE hearing aids often have to choose between VC and telecoil. Then, while they are able to access the hearing loop via the telecoil, they are unable to adjust the volume to their liking. If the voice that is using the systems’ microphone is a very loud voice, it’s a bad experience because it is way too loud. On the other hand, if the voice is very soft, it’s a non-experience. Often more than one person is speaking to an audience. Controls are a must. I appeal to manufacturers and sellers of hearing instruments to consider these issues. They are far more important than anyone who does not experience hearing loss personally can possibly understand. Let’s get heads out of the sand on this one. Please!

I’ve worn two aids for about 15 years. I consider user VC essential, regardless of what else is built in. First, we all know that lots of hearing aids never leave the drawer. Are there any figures on usage of VC versus non-VC aids? Second, it’s not just the input levels that change, the user’s level of interest in the environment changes. When I’m in a bus or train, the background noise is very loud, and I have no need to talk to people, so I turn the volume way down. So thanks for questioning the trend to non-VC aids.

I have been voicing my displeasure about lack of volume control ever since I have been using my present aids. I cannot control volume with telecoil on. It is always much too loud. Why aren’t professionals aware of this problem? Why have a telecoil if it is unusable?