By James Curran

Earl Harford, Ph.D. 1929-2016

Recent generations of audiologists may have heard Earl Harford’s name from their teachers or run across one of his many publications and writings during their student years. But only those of us who were there from the early days really know who he was and what he meant to our profession. Earl Harford was, I can say without serious contradiction, the father of private practice hearing aid dispensing, outspoken in his conviction over the years that dispensing was a significant component of audiology’s scope of practice. Every step he took in his entire career, in one form or another was dedicated to improving the delivery of amplification by audiologists to the hearing impaired.

He was one of the first 75 audiologists in our profession, and was fortunate to be among the chosen few who were the first students and acolytes of Raymond Carhart at Northwestern University. His classmates included Jim Jerger, Noel Matkin, Wayne Olsen, Bill Rintelmann and Tom Tillman, among others, all of whom, as we know, went on to make lasting contributions to the profession. After receiving his doctorate, he spent a few years at McGill University in Canada, and then was asked to join the faculty at Northwestern.

It was there he found his true vocation and formed his abiding and lifelong interest in amplification. He once told me the only job open for him when he joined the faculty was to run the Hearing Clinic, a not very desirable career option, for anything that had to do with hearing aids was then and would remain for decades the lowest position on the audiology totem pole. But he embraced the opportunity to make a difference.

He realized that you could drive a truck through the inconsistencies and unpredictability of the comparative hearing aid evaluation, and further, that the person who was actually responsible for the success of the fitting was the hearing aid dispenser (dealer) who had received the clinical referral. Ironically, if a dealer desired referrals from the Hearing Clinic, he suffered the insults and shabby treatment meted out by audiologists who thought and acted as if they knew what they were doing, but really didn’t. Realizing the unfortunate incongruity between what he had been taught and practiced, and the reality of the situation, he began visiting, making friends and learning from a few of the most competent, skilled dealers in the Chicago area. This experience confirmed for him that the education audiologists were receiving about amplification was tragically lacking, and faulty both in content and practice.

But his personal understanding and appreciation of the problem wasn’t worth much to him academically or career-wise at that time. Nobody really cared, for the profession was on fire developing and perfecting site of lesion tests, moving away from the rehabilitative side of audiology. But his new insights hardened into a private, life-long determination to improve in any way he could the area that audiology was leaving behind, the fitting of hearing aids.

Earl was a teacher at heart, and he loved the academic life. He smoked a scholarly pipe, wore scholarly leather patches on his scholarly tweed jacket, and learned and practiced well the scholarly ways of an up and coming young faculty member. He bought into the idea that audiologists should not be engaged in the commercial world, although he reversed his thinking some years later. As a faculty member for nearly two decades he turned out a bundle of scholarly papers and mentored many masters and doctoral students in their theses and dissertations. And he became, because of his writings about amplification at the time, the only academic audiologist that was halfway trusted and consulted by the industry. He especially eschewed the disdainful attitude toward hearing aid specialists and manufacturers that was standard practice by most audiologists.

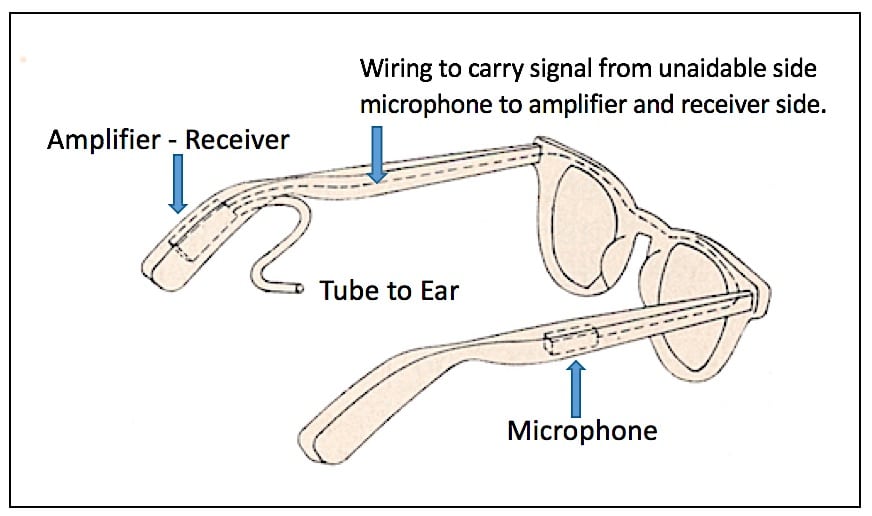

All the while the need for improving the fitting of hearing aids nagged at him. Then by a lucky confluence of events he discovered the usefulness of CROS aids for unilateral deafness. With a student, Joe Barry, he published the first known paper in the literature describing open canal amplification. The CROS (Figure 1) aid with separation between microphone and receiver reduced feedback issues, and it was determined that the best candidates were those patients that had some hearing loss in the aidable ear. From there it did not take long to start fitting CROS aids to bilateral high frequency losses, a revelation, for in those days, most ear level aids for high frequency losses used closed molds and small vents to minimize feedback. In one fell swoop CROS fittings provided excellent amplification in the high frequencies (although for only one ear, but that was the standard practice at the time) with no attendant occlusion effect. Thereafter, the literature exploded with studies showing the advantages of open canal amplification, and it was reported that fully 40% of the referrals from University clinics were for CROS aids. Industry records show that during those years about 20% percent of the aids sold in North America were CROS.

Figure 1. CROS concept, where CROS stands for Contralateral Routing of Signals. In the eyeglass example shown, the microphone, placed on the unaidable ear side (of a unilateral hearing loss), picks up the signal on that side, and via wires, carries the signal to the opposite/contralateral ear that has normal or near normal hearing. The signal is amplified and sent by the hearing aid receiver/speaker to the good ear, delivered via an open tube to allow normal sounds to be heard by the normal ear as well.

Despite its early success, open canal amplification died out when custom hearing aids were introduced, but from personal experience I know the introduction of the open canal rationale was responsible for many hardy, resolute pioneer audiologists to begin to quietly dispense commercially and defy the edicts of ASHA. Open canal amplification by means of CROS aids allowed them to provide a listening experience heretofore unachievable. This was the true beginning of audiology incorporating dispensing into its scope of practice. Today, due to advances in feedback cancellation, it is estimated that open canal amplification, introduced by Harford many years ago, accounts for a majority of all hearing aids fitted.

Throughout his career he continued to investigate and develop methodologies and understandings related to improving hearing aid fitting. For example, it was in his Clinic at Northwestern where he, along with David Preves and Bill Austin from Starkey, discovered that by contrast to BTE hearing aids, custom hearing aids provided greater gain in the high frequencies because of the position of the hearing aid microphone in the concha. This realization, astounding for its time, was one of the foundations for the rapid growth and acceptance of custom amplification throughout the world.

After leaving Northwestern, he directed the program at Vanderbilt University for a short time and then became Professor and head of the audiology program in the Otolaryngology Department at the University of Minnesota Hospitals. He began to experiment with newly available miniature microphones recently developed by Knowles Electronics. There were no probe tubes available at the time, but he was able to obtain in situ recordings of the amplified response by inserting the mikes deep down in the ear canal, beyond the tip of the earmold, next to the tympanic membrane. He published the first papers reporting the methodology and his findings; their impact was palpable, for soon after, commercial stand-alone instrumentation became available making real ear measurements affordable and routine. It is generally agreed, based on this pioneering work, that he virtually invented the use of real ear measurements in hearing aid fitting.

This was a time of ferment in audiology. Two big issues faced the profession, first, whether audiologists should be allowed to dispense, and second, whether audiology should transition to a doctoring profession. Earl came down hard on the right side of the issues, and consistent with his beliefs, he brought his considerable personal and professional reputation to bear to make dispensing a critical and necessary part of audiology services at U of M hospitals. He opened perhaps the first for-profit hearing aid dispensary in a University medical setting at a time when the field still looked upon dispensing as a marginally unethical undertaking. This caused an uproar. The otolaryngologists were outraged that he structured the clinic so that the staff audiologists benefitted financially from the practice. And almost to a man, the faculty on the academic side of the University, clinging to old beliefs, condemned and opposed his program. The upshot of his forward thinking and brave decision was that he lost his job, and eventually his tenure at the University. He paid an enormous price for his dedication to what he felt was the right thing to do.

He knew his academic career was over so he used his savings to open a private practice audiology clinic in Minneapolis, emphasizing of course, the dispensing of hearing aids. Dr Harford’s obvious and widespread knowledge of hearing aid amplification coupled with his considerable personal charm resulted in his practice becoming an outstanding success. It is here, without the protective covering of an institution, that he gained the crucial experience and expertise required to maintain and continue a successful private dispensing practice. In less than ten years he built the practice up to a point where he could sell it and retire in comfort to his beautiful lake home in northern Minnesota.

But he wasn’t finished yet. Starkey Labs then offered him a consulting position asking him to use his experience to develop an educational program for Starkey employees and customers. From scratch, using the resources of the company, he put together a novel internship program for improving competence in dispensing for graduate students in audiology. Students from all over the country competed for scholarships that granted them housing, meals and a stipend for a period of six weeks at the factory. I watched him win over the doubtful within the company who didn’t initially see its value and purpose. During their six weeks, the interns immersed themselves in the various departments, including production, design and product development, learned how to craft earmolds and finally, built an entire hearing aid from start to finish for themselves. The interaction between employees on the line and students was extremely beneficial, for the employees found out, contrary to rumor, that audiologists didn’t wear horns, and the students realized that management and manufacturing personnel were not improperly motivated, a pervasive sentiment within audiology over the years.

I became his co-instructor, and remarkably, we found we had formed exactly the same point of view about what we should be teaching. We taught what Earl termed “stick shift” fitting asking the students to decide how to fit a patient using only an audiogram and patient history, with no help from any fitting software. Over the years we awarded scholarships to over 150 students from Universities and training programs in the U.S. and abroad. I watched his interactions with our students. He was fatherly, thoughtful, patient and balanced, was one of the few I knew who actually was able to suffer fools gladly, and the students loved him. The program ended when Earl came down with leukemia, and then both he and I retired within a few months of each other.

There isn’t much more to add, except that he fully realized the goal he had set for himself decades ago. In his vita he wrote that his area of specialization was improving amplification for the hearing impaired. Many audiology professionals may have espoused such a notion, but few lived it as well as Dr Harford. The profession owes him an enormous debt of gratitude, and his contributions shall not be forgotten.

Ave, atque, vale Earl; may you rest in peace.

James Curran was one of the first of a group of pioneering audiologists to be employed in the hearing aid industry, and is recognized internationally through his writings and presentations. He was a colleague of Dr. Harford at Starkey Labs.

I am so sad to hear we have lost Earl. I was in the 2nd class at Starkey and Dr. Harford’s influence changed my my course in Audiology. He helped me find my gift and my passion (Jim you did too in this program!) I would not be where I am today without his guidance and belief in me. He gifted me with so very much. One of my office’s lobby has part of his collection of hearing help devices throughout the past 100 years. I treasured it, but now there is added love and a sense of loss. Thank you for this post Mr. Curran

Thank you for sharing Dr. Harford ‘s story. May he Rest In Peace.

Wonderful tribute to a man who did so much for so many.

I am so sorry to hear of his death – He was certainly an inspiration to me in 1975 when I started my private practice, and over the years, I had the opportunity to speak with him a number of times. Thanks, Jim for sharing these memories.

Jim,thank you very much for the rememberance! It puts a smile on my face thinking of Earl. When, in 1993, he was asked by a few of us graduate interns what he wished for he stated, with his sly grin, that he wanted our age! He had so many things that he still wanted to do, and over the course of the next 20 years did! He will never be forgotten!