This post is a continuation of Part 1 by Dr. Carol Bauer which introduced the concept of Rational Drug Treatment for Tinnitus – The Gabapentin Story, or Why Aren’t the Pills Working? An example of following the need for a proper rationale, and evidence supporting tinnitus drug treatment, using the drug gabapentin as an example, is the topic of Part 2.

Dr. Bauer is Professor and Chair of the Division of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery at Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, Springfield, Illinois, and a recognized international authority on tinnitus.

Her areas of interest and expertise relate to hearing loss, balance disorders, and evaluation and management of tinnitus (ringing in the ears). It is this latter area in which she is writing here about her research – research dedicated to understanding the central mechanisms responsible for generating tinnitus, and to develop effective strategies for tinnitus treatment.

Desire to Treat Tinnitus with a Pill

The desire to cure tinnitus with a pill is powerful. Patients suffering from tinnitus can be desperate for relief and a pill that would eliminate, or at least significantly reduce, the bothersome-ness of their tinnitus would be welcome. Many people with less intrusive tinnitus that is not burdensome, would also be motivated to take a medication for their tinnitus, provided that it completely eliminated their tinnitus with minimal side effects, was relatively inexpensive or covered by third-party payers, and did not entail a life-long medication regimen.

Pharmaceutical companies are very interested in finding a pill to treat tinnitus, for obvious reasons. It should not be surprising, then, that the list of prescription and non-prescription drugs that have been investigated or sold as drug treatments is very, very long. The combination of a vulnerable, sometimes desperate population of patients seeking relief, and the lure of lucrative profits from selling a medication for tinnitus, is a recipe for a market flooded with quick fixes and tempting trials.

Drug Development and Serendipity

Development of a new drug for any medical problem is an expensive process that requires decades of investigation and is fraught with failure. Repackaging existing drugs for new indications is a useful short-cut and occasionally is successful.

Occasionally, a drug developed for one purpose has an unexpected positive side effect. For example, minoxidil was developed to treat high blood pressure, but was observed to increase hair growth. It is now marketed as Rogaine®.

There have been no new drugs developed specifically for tinnitus (I will explore the reasons and a proposed solution for this in Part 3 of this series). All drug trials to date for tinnitus have studied existing drugs or drug combinations that were re-purposed from a different indication. Sometimes the reasons for examining a candidate drug are rational and obvious; for example, using benzodiazepines such as alprazolam (Xanax) to modulate the distress associated with tinnitus. Less obvious compounds examined include honey bee larvae to treat tinnitus, purportedly through modulation of stress hormones.

Drug choices can be selected by targeting specific theoretical mechanisms – for example using Tegretol, an anti-seizure medication, to stabilize the neural activity that may be responsible for tinnitus. Frequently though, a drug is investigated or publicized as a useful medication for tinnitus, without evidence or rationale. A good example of this is gingko biloba, a naturally occurring mixture of compounds derived from the gingko tree, with a variable range of bioactive properties that include neuromodulation, neuroprotection and anti-oxidant properties.

Figure 1 provides a partial list of some of the drugs, herbal, or health supplements that have been suggested as potentially treating or curing tinnitus, but without evidence or rationale.

Figure 1. A list of some of the drugs, herbs, or health supplements that have been “offered” to treat and/or cure tinnitus. What is missing from these is the rationale and evidence of performance.

The Gabapentin Story – As an Example

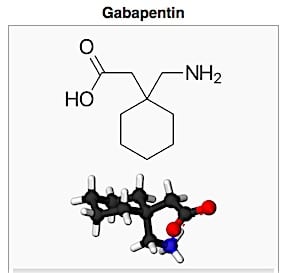

Arguably, one of the drugs that has been studied most extensively as a tinnitus treatment is gabapentin (marketed as Neurontin®). It is useful to look at the history of this drug to appreciate the promise and pitfalls encountered when searching for effective tinnitus treatments. Gabapentin was developed and FDA-approved for use as an adjunct medication for control of epileptic seizures and specific forms of chronic pain. As with many drugs, it is also commonly used ‘off-label’ for non-FDA-approved conditions including migraine and diabetic neuropathy.

Arguably, one of the drugs that has been studied most extensively as a tinnitus treatment is gabapentin (marketed as Neurontin®). It is useful to look at the history of this drug to appreciate the promise and pitfalls encountered when searching for effective tinnitus treatments. Gabapentin was developed and FDA-approved for use as an adjunct medication for control of epileptic seizures and specific forms of chronic pain. As with many drugs, it is also commonly used ‘off-label’ for non-FDA-approved conditions including migraine and diabetic neuropathy.

Because tinnitus commonly had been considered to have mechanistic similarities to chronic pain, neuropathy and epilepsy, the application of the drug to treat tinnitus was predictable. In 2001, Zapp1 reported nearly complete resolution of tinnitus in one patient with new onset symptoms, with off-label use of gabapentin. The drug was subsequently reported by Shulman et al. (20022 and 20033) to be effective in several case series, when combined with the benzodiazepine Clonazepam. These results, combined with evidence from animal studies and the growing body of literature demonstrating loss of inhibitory neurotransmitter activity in the de-afferented or damaged auditory system, prompted us to design and conduct a placebo-controlled trial of the drug.

Drug Trial Using Gabapentin for Tinnitus

The importance of including a placebo group in a clinical trial investigating treatment of a very subjective clinical problem such as tinnitus cannot be overstated. Duckert and Rees (19844) reported that 40% of participants in a study receiving a placebo injection noted a change in their tinnitus. In our trial, participants served as their own control, and were blinded to the series of placebo and active drug doses (800 mg, 1800 mg, 2400 mg) used in the study. We measured participant response to treatment using standardized questionnaires, global improvement ratings and objective psychoacoustic measures of tinnitus loudness.

The importance of including a placebo group in a clinical trial investigating treatment of a very subjective clinical problem such as tinnitus cannot be overstated. Duckert and Rees (19844) reported that 40% of participants in a study receiving a placebo injection noted a change in their tinnitus. In our trial, participants served as their own control, and were blinded to the series of placebo and active drug doses (800 mg, 1800 mg, 2400 mg) used in the study. We measured participant response to treatment using standardized questionnaires, global improvement ratings and objective psychoacoustic measures of tinnitus loudness.

We hypothesized that tinnitus associated with different causes (noise damage, age-related hearing loss, Meniere’s disease) could have different pathological mechanisms and suspected that treatment response would be variable according to tinnitus etiology. We therefore enrolled two categories of study participants: those with audiometric and/or historical evidence of noise damage as the cause of tinnitus, and a cohort of participants without evidence of noise damage. Our results showed that, although there was a range of responses seen in both groups, the improvement in subjective tinnitus severity and objective loudness estimates was of greater magnitude and occurred in a larger percentage of the participants with a history of acoustic trauma than those without a history of acoustic trauma5.

Subsequent controlled clinical trials of the effects of gabapentin on tinnitus have yielded suggestive but not consistent results. Witsell et al. (20076) observed a strong placebo effect in their study, however, a significantly larger number of subjects in the gabapentin group reported improvement on a global severity score compared with placebo group (37.5% vs 6.7%, p < 0.026). It is important to note that only a single drug dose was used in this study (1800 mg daily), and objective measures of tinnitus loudness were not obtained. Piccirillo et al. (20077) also studied a single drug dose (3600 mg daily) in a study enrolling participants with tinnitus of any etiology. A standardized questionnaire of tinnitus severity, the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI), was the primary outcome measure. They reported no difference in THI score between placebo and active treatment groups overall. However, there was a significant difference between treatment groups for subjects with normal hearing (21.4-point decrease with gabapentin, 1.75-point decrease with placebo, p=0.005). The criteria for categorizing normal hearing were not reported, and therefore, it is unknown if these participants had evidence of noise damage with a notch at 4 kHz on pure-tone audiometry.

Controlled clinical trials investigating the effects of gabapentin on tinnitus have produced inconsistent results, with some studies suggesting a placebo effect and others indicating improvement with gabapentin use. However, these studies utilized a single drug dose and did not include objective measures of tinnitus loudness. While one study showed no significant difference in overall tinnitus severity between placebo and gabapentin groups, a significant improvement was observed in participants with normal hearing in the gabapentin group.

Elements of Trial Design to Investigate Promising Anecdotal Reports

It is clear that the design and execution of clinical trials to investigate promising anecdotal reports of therapeutic efficacy is complex.

There are a number of key elements to consider when designing a tinnitus trial. These include acknowledging that multiple etiologies with different mechanisms may cause tinnitus; one drug may not be effective for all forms of tinnitus. Enrollment stratification for tinnitus type and severity as well as comorbid conditions of depression and anxiety should be considered. Unless there is a priori evidence for an optimum drug dose, multiple dose levels should be included in the trial. The selection of primary and secondary outcome measures also requires careful consideration.

As I discussed in Part 1 of this series, it is important to establish a goal for the treatment and then implement the appropriate outcome measures that are sensitive to that goal. If decreasing tinnitus loudness is the objective, then psychoacoustic measures of tinnitus that are valid and reproducible should be employed. If improvement in attention and emotional reaction to the tinnitus are the goals, then standardized questionnaires that assess these elements are required. Finally, the inclusion of a well-designed placebo arm is a critical feature of clinical trials involving tinnitus.

Current Status of Drugs, Herbal, or Health Supplements for Tinnitus

It is important to remember that, at least for now, there is no drug or herbal or health supplement that has been demonstrated to be broadly effective in improving tinnitus with consistent results from well-controlled repeated trials. Benefits have been reported anecdotally for individuals with a variety of medications, and trials for some drugs, such as gabapentin, have shown promise for specific types of tinnitus.

In Part 3 of this series I will discuss how we can advance scientific knowledge in the field and use this knowledge to develop effective drug treatments for tinnitus using animal models.

References

- Zapp, J.J. (2001). Gabapentin for the treatment of tinnitus: A case report. Ear, Nose & Throat Journal, 80, 114-116.

- Shulman, A., Strashun, A. M., & Goldstein, B. A. (2002). GABAA-benzodiazepine-chloride receptor-targeted therapy for tinnitus control: Preliminary report. International Tinnitus Journal, 8(1), 30–36.

- Goldstein, B. A., & Shulman, A. (2003). Tinnitus outcome profile and tinnitus control. International Tinnitus Journal, 9(1), 26–31.

- Ducker, L.G., and Rees, T.S. (1984). Placebo effect in tinnitus management. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1984; 92(6):697-9.

- Bauer, C.A., and Prozoski, T.J. (2006). Effect of gabapentin on the sensation and impact of tinnitus. Laryngoscope. 2006 ;116(5):675-81

- Witsell, D.L., Hannley, M.T., Stinnet, S., and Tucci, D.L. (2007). Treatment of tinnitus with gabapentin: a pilot study. Otol Neurotol. 2007 ;28(1):11-5.

COMPLETE CURE TO TINNITUS: I had tinnitus in both ears for fifteen years with a high pitched two tone sound, the noises are constant and have learned to ignore the ringing. Later, another sound was added, a deep tone that has a sporadic rhythm, that mimics human speech. It varies from soft and muted, to painfully clear, and loud. Have try sound machines, ear plugs, my hearing aid, and medication all to no avail rather I have a difficult time sleeping. Lately I was directed to a Doctor on internet who provided solution to the problem. Do not be discourage, there is hope for you, it is a permanent cure to Tinnitus.