This post continues the comments by many hearing professionals expressing concerns that OTC hearing aid sales will result in dissatisfied users because:

- The instruments are not professionally fitted

- An audiogram is necessary

- OTC-sold devices (previously/also defined as PSAPs) are of poor quality and will not meet the needs of the hearing impaired, and

- Poor experiences by the purchaser will discourage them from seeking additional assistance and purchasing a “real” hearing aid

- A Universal, basic hearing aid cannot manage all hearing losses

The objection that hearing aids are not fitted professionally in an OTC model, that an audiogram is necessary, and that OTC/PSAP product quality is poor and will not meet the needs of the hearing impaired, were discussed in previous posts.

This post looks at comments that an OTC-sold device (which can include PSAPs or OTC hearing devices) will result in poor experiences by the purchaser and will discourage them from seeking additional assistance and purchasing a “real” hearing aid. This post jumps to various topics, some of which will be dealt with in greater detail in future writings.

Traditional Hearing Aids Versus PSAPs and/or OTC Hearing Aids

Are Hearing Aids Preferred Over PSAPs and/or OTC Hearing Aids by Users?

Limited Data Exists

To the best of this author’s knowledge, there are no viable studies that support the contention that hearing aids are preferred by consumers over OTC/PSAP products. There are at least a few major problems when attempting to make comparisons of PSAPs and hearing aids:

- Investigator bias. (The commitment by the investigator to the product in question – either professionally and/or financially).

- PSAPs used for comparisons in the studies and evaluated electroacoustically. Figures 1 and 2 provide PSAP examples from studies in Hong Kong and Europe.1,2 In reviewing the products, which were measured electroacoustically, it appears that these studies considered PSAPs as instruments having external button receivers primarily. It is possible, but not probable, that there were no open or RIC-type PSAPs available for these studies unless those parts of the world are less sophisticated in product development. Figure 3 shows PSAPs that were available, at least here in the U.S. during these comparison testing periods, but essentially ignored. All but one of the instruments in Figure 3 retail for less than $500, and are sold as PSAPs/OTC aids.

- Study dates. Older studies in which PSAPs were compared are unlikely to represent current PSAPs and OTC products. Many current PSAPs and OTC hearing aids contain many of the same components found in high-end hearing aids: digital amplification, high-end feedback cancellers, microphones for omni-or directional performance, quality speakers, volume controls, T-coils, different listening programs, rechargeable, etc. Current PSAP/OTC hearing aids are available in both open and RIC configurations. True, one can find $29 products, and while they do not have the quality of PSAPs in the $300 to $500 range, even they can be helpful for some individuals, depending on the interest needs of those individuals. In that sense, they might be better compared with hearing aids of 50 years ago or so. To say that hearing aids of yore did not help anyone would be a misstatement of fact and an indictment of the hearing aid industry at that time.

Figure 1. PSAPs evaluated in the study by Chan and McPherson, 2015. All instruments, with the exception of in-the-ear devices, utilized external button receivers.

Figure 2. A sampling of the PSAPs used in the 2015 European hearing aid industry study. Heavy emphasis was on those instruments having external button-type speakers.

Figure 3. Instruments identified as PSAPs that were available, at least in the U.S. during the times that the studies identified in Figures 1 and 2 were conducted. Most consist of open or RIC-style instruments. Only one has an external button-type receiver. It is possible that none of these were available in Europe and Hong Kong during the time of those studies.

Consumer Preference

Figure 4. Audiograms of the 20 subjects in this study, with the average audiogram in red. The hearing loss range was reported in the study as ranging from mild to moderately-severe.

Another way to compare PSAPs and hearing aids, other than by electroacoustical measurements, is by consumer preference. In a preference study of hearing aids versus PSAPs, 20 subjects, ranging in age from 26 to 83 years of age, with the hearing thresholds shown in Figure 4, were involved3. Nine subjects were experienced hearing aid users.

The study included two premium hearing aids, two basic hearing aids, and two PSAPs. Two manufacturers supplied the four hearing aids, and two companies supplied the two PSAPs. All devices were adjusted as best they could to match NAL-NL2 targets. Note: one of the PSAP units allowed only two gain setting adjustments (low and high), and no response adjustments, etc. The hearing aids were real-ear measured on KEMAR (closed dome) as best they could to match NAL-NL2 targets. This means that the PSAPs were primarily the basic response of the unit as off the shelf and could have been some distance from the NAL-NL2 target gains. Amplified quiet speech, noises, and music stimuli were digitally recorded in WAV format and presented to the subjects. Subject testing consisted of preference scores on one ear using an ER-2A insert earphone to present the recorded stimuli for each of the hearing aids, with the other ear plugged. A double round robin, random order, was employed for presentation order, for 30 comparisons.

Results are shown in Figure 5. PSAPs performed as well in this laboratory study as hearing aids (basic and premium) for everyday noises and music, but not for speech.

Figure 5. Preference scores from 22 adults for hearing aids versus PSAPs for the listening conditions of quiet speech, noises, and music.

Interestingly, even though the PSAPs could not be adjusted to the NAL-NL2 targets with the same finesse as the hearing aids, it is informative to note that for speech in quiet, where the hearing aids scored higher than the PSAPs, the differences were less than 5 preference scores poorer than the premium hearing aids. And, the basic hearing aids (A and B) scored higher in quiet than the premium-priced hearing aids). The poster did not break out the experienced user preference scores for these measurements, but it would have been informative to view their preference scores to determine how their experience may or may not have influenced the overall scores. Of some interest also, is that the OTC market is proposed for mild-to-moderate hearing losses, but some of the subjects in this study might be viewed as having hearing levels beyond this category. As a result, this study suggests that losses even in the moderately-severe category might have results expected to be similar to those reported here.

A study that attempted to get at information as to how well consumers responded to the medical model versus the OTC model resulted in more questions about the design of the study than usable results.4

Consumer Interest in OTC Hearing Devices

This issue seems to be missing in any discussion of OTC products, but it would seem to be of obvious significance.

In previously unpublished data included in a private meeting presentation to the FDA in 2001, interest by non-hearing aid users in an OTC disposable hearing aid was strong (Figure 6).

Non-users of hearing aids would seriously consider OTC products at a combined 58% (17% definitely would buy and 41% probably would buy). Of additional interest was that 35% of existing hearing aid users would probably, or definitely, purchase an OTC product, only down 10% from purchasing a prescription (Rx) product.5

By far, the greatest movement in hearing aid interest was by the non-user, and for an OTC product.

One might conclude that these data don’t apply because the instruments in question were disposable. A good marketer might counter by realizing that disposable hearing aids were shown to be of interest, and perhaps such a category should be produced and sold.

Figure 6. Interest in OTC disposable hearing aids by hearing aid users and non-users of hearing aids.3 The comparison is to prescription hearing aids following the current medical model of hearing aid sales.

OTCs Will Provide Poor Results and Are of Lesser Quality. Thus, a Bad Experience Will Discourage Users from Trying Real Hearing Aids

What does this mean? What defines “poor results” and “lesser quality?” The issue of OTC hearing products being of lesser quality has been qualified in a previous post. Is it possible that a bad experience with a “real” hearing aid might lead to a person trying an OTC product where the commitment is with a small “c” rather than a capital “C” – being satisfied with the OTC cost/benefit?

What Constitutes Poor Results?

Do “poor results” mean that an OTC hearing aid (which could also be a PSAP):

- Cannot meet the amplification needs of the user?

- There is no way to determine that they meet appropriate target gains?

- They are not used all the time, or never? End up in a “dresser drawer”?

- There is nobody to adjust the aids or provide counsel when needed?

- Has no recorded benefit?

Interestingly, these seem to be the same questions that current research is asking about professionally-fitted hearing aids. Evidence seems to be AWOL (absent without leave) that OTCs will provide poor results. This must await the actual distribution model.

Satisfaction?

How would an OTC hearing aid compare with professionally fit hearing aids in terms of overall satisfaction? There is a dearth of available studies making this comparison, but a plethora of studies looking at consumer satisfaction with traditional hearing aids. In those studies, satisfaction is related primarily to issues mostly unrelated to the hearing aid’s electroacoustical performance:6

“Various studies have used these tools to examine the relationships between satisfaction and other factors. Findings are not always consistent across studies, but in general, hearing aid satisfaction has been found to be related to experience, expectation, personality and attitude, usage, type of hearing aids, sound quality, listening situations, and problems in hearing aid use.”6

It has been reported that 35% of patients with no measurable benefit (APHAB) were satisfied with their “real” hearing aids7. And, interestingly, as suggested in the above quote, only 43% of overall satisfaction was related to the device, with benefit scoring poorer than satisfaction.

Quality

The concern that some have expressed is that OTC instruments (hearing aids and PSAPs), are insufficient to manage properly the needs of the hearing impaired – that they are of lesser quality.

Comments have stated that quality is poor1,2 as measured electroacoustically, and because of this, speculation has led to an assumption of unsatisfactory performance by the hearing impaired. And thus, this would discourage consumers from considering more premium-priced amplification – that of the traditional hearing aid. Other than anecdotal comments by those opposed to PSAPs and OTCs, no evidence can be found to support this position.

How Good Does Hearing Amplification Have to Be?

This is the million-dollar question, and no qualified answers have been forthcoming.

A strong case for the growing demand of medical devices that are “good enough” comes from a McKinsey Report.8 The Report states that “good enough” are devices that are lower priced and don’t possess many of the value-added features that are often found in the premium category.

What should be of interest is that this new market segment, one valuing no-frills solutions, is growing twice as fast as the industry as a whole in many medical device categories. Granted, this Report does not directly mention hearing aids, but as Taylor commented, “It is not too big of a leap to draw parallels to the commoditization of technology occurring within our own profession.”8

The following questions based on how good a hearing aid amplifier has to be has been collected from different bits of information attributed to Killion.9

- Must it meet arbitrarily-determined and proprietary-fitting formulae target gains? Since there is no standard optimal fitting formula, it is difficult to use meeting these target levels as a guideline. A fundamental assumption in the professional fitting of hearing aids is that the gain-frequency response of the instrument needs to be individualized to the patient’s hearing loss. Is this factual?

- Must it meet some undefined real-ear (RE) target? If the RE target is based on a fitting formula that provides no standard optimal amplification, a same arbitrarily undefined goal would result.

- Should there be a certain improvement in word recognition scores? This would be a dangerous approach, unless one ignored PB max measurements and instead looked at unaided versus aided scores at a normal conversational level.

- Should a certain SNR (signal-to-noise ratio) minimum be expected? What if there is no improvement but the patient is satisfied with the amplification?

- Should an OTC hearing instrument have multiple programs, or some minimum? Studies have shown that the majority of people use one setting about 80% of the time, and some never go beyond the single setting.

- Does it require streaming capabilities or advanced adaptive features? Are all the bells and whistles needed, and even worse if they are never used? How good must a hearing aid be to meet the needs of the individual? Should this not be the primary function to address? If the person says that the hearing aids work for them, and they are satisfied, has not the need been met?

A well-known and highly-respected audiologist recently commented, and confirmed to this author via e-mail the following:

“I remember well the body aids (with Y cord) that were available in the 1950’s…my HOH students in California wore them and did quite well. I am relatively certain they were not as good as some of today’s PSAPs.”

When favorable words about amplification can be heard even from some people who have purchased $39 units, it is logical to ask, “what is going on”?

Perhaps the basic question to ask, as some have suggested is, does customer satisfaction result from advanced amplification features, or primarily from amplification?

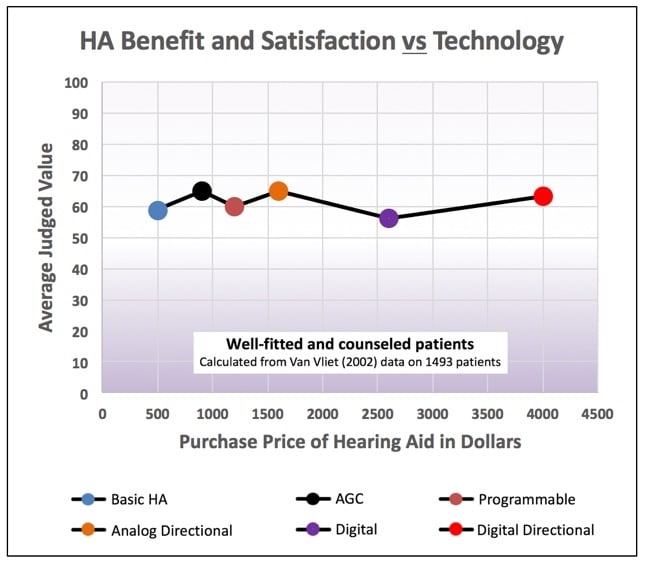

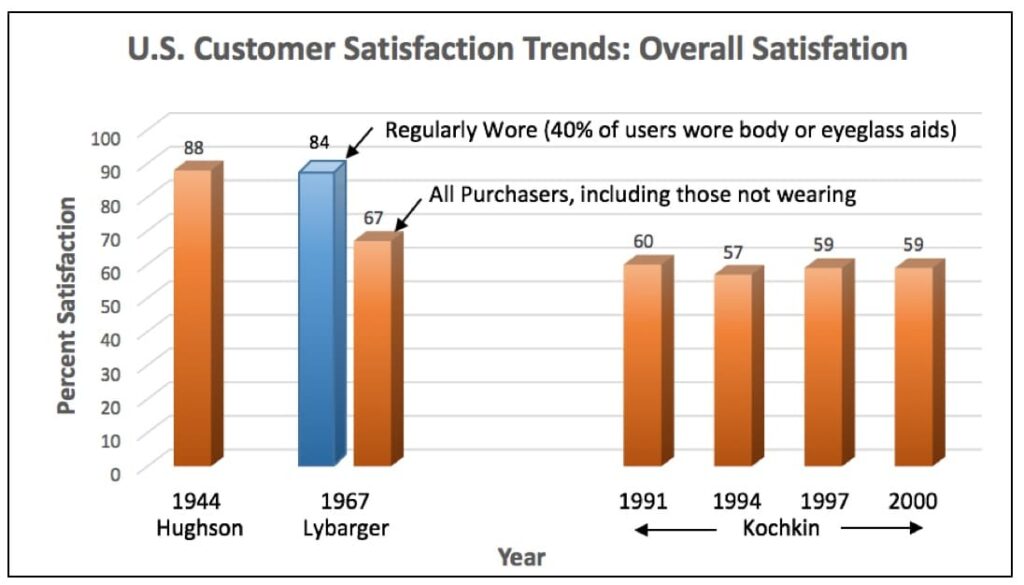

In a study by Van Vliet in 2002, 1499 patients of well-fitted and counseled patients were asked to judge the average value of binaural Basic, AGC, Programmable, Analog Directional, Digital, and Digital Directional hearing aids. The average judged value was 60 (on a scale from 0 to 100) for all the devices, regardless of the purchase price10. In this study, the instruments with the most features had the highest purchase price (Figure 7). Additionally, Figure 8 shows that even with advanced features, U.S. customer overall satisfaction with hearing aids did not improve from 1944 through 2000 (with the most recent data showing satisfaction at about 60%)11,12,13. Lybarger (1967) reported customer satisfaction with hearing aids for all purchasers at a little over 65%. All users, however, reported satisfaction at about 85%, and this was with 40% body or eyeglass hearing aids in the mix11. The satisfaction percentage from Hughson in 1944 was essentially all with body-worn hearing aids12. Is it possible that the lower satisfaction today reflects consumer expectations based on promotional information? Regardless, this is not a healthy trend.

Figure 7. The average judged value for all the devices, regardless of the purchase price, was about 60, regardless of the advanced features. (Calculated by Killion from Van Vliet, 2002 data).

Figure 8. U.S. hearing aid trend for customer overall satisfaction with hearing aids, 1944 to 2000. Various sources.

Future posts will continue along the lines of PSAP/OTC hearing aids, including information relative to self-fit, the proposed Personal Sound Amplification Performance Criteria of the Consumer Technology Association (CTA), and “universal” hearing amplification.

References

- Chan ZYT and McPherson B. (2015). Over-the-Counter hearing aids: a lost decade for change. BioMed Research International, Vol. 2015, Article ID 827463, 15 pages.

- European Association of Hearing Aid Professionals (AEA)/European Federation of Hard of Hearing People (EFHOH), Paper on the potential risk of using ‘Personal Sound Amplification Products’ PSAPs (Dec. 2015).

- Xu, J., Johnson, J., Cox, R., and Breitbart, D. (2015). Laboratory Comparison of PSAPs and Hearing Aids. American Auditory Society, Scottsdale, AZ, March, 2015.

- Tedeschi T. and Kihm J. (2017). Implications of an over-the-counter approach to hearing healthcare: a consumer study. The Hearing Review. 24(3) March; 14-22.

- Songbird FDA Briefing. (2000). Disposable hearing aid concept test, July. Staab Files.

- Wong LN, Hickson L, McPherson B. (2003). Hearing aid satisfaction: what does research from the past 20 years say? Trends in Amplification, Fall: 7(4): 117-161.

- Kochkin, S. (2002). 10-year customer satisfaction trends in the US hearing instrument market. MarkeTrak VI, The Hearing Review, October.

- Llewellyn C, Podpolny D, Zerbi C. Capturing the new “value” segment in medical devices. January 2015.

- Killion M. Based on what the author has taken from various communications (all kinds) and writings of Killion.

- Van Vliet, D. (2002). User satisfaction as a function of hearing aid technology. Paper presented at: American Auditory Society Scientific/Technology Meeting, March 14-16, Scottsdale, AZ.

- Hughson, W. and Thompson, E. (1944). Archives of Otolaryngology, 39:245-249.

- Lybarger, S. (1967). Referenced in: Killion, M. (2004). Myths about hearing aid benefit and satisfaction. The Hearing Review, August, pp 14, 16, 18-20, 66.

- Kochkin, S. (2002). 10-year customer satisfaction trends in the US hearing instrument market. MarkeTrak VI, The Hearing Review, October.

The consumer interest in OTC hearing aids, I believe, was brought on by the high markup charged by Audiologists. Perhaps the closed nature of the industry is a contributing factor too, ie it is impossible to find anywhere an unbiased comparison of the different brands; not on the internet nor in Consumer Reports. This keeps the consumer uninformed and at the mercy of the Audiologist who will push only the brand he dispenses. That did not matter years ago, but in the computer age it is very different. Those consumers entering the age group where hearing problems begin are computer literate. They will question and expect valid answers. The Hearing aid manufacturers are aware of these changes. Not all Audiologists are. Manufacturers have discounted name brand hearing aids which are now dispensed at Sam’s, Costco and on EBay having the same hearing benefits as the instruments sold at twice( or more) the price by private sources. There are now Audiologists willing to fit these instruments and service them a la carte. The cracks in the previous monopoly are are showing. If they are to widen depends on the reaction by Audiologists. Where am I wrong?