How loud can sound get? Could loud sound kill you? Are there limits, and if so, what are they? How are such things determined? All of these are interesting questions and an attempt will be made to answer these as best possible.

Two important lessons are supported by this article: one, the loudest thing in the world does not have to be seen to be heard and two, just because you can’t hear the sound doesn’t mean it isn’t there.

It seems appropriate that any rank ordering should be divided into non-living things and living things, including animals. As a result, all sounds/events in this article are known, not speculated upon based on past eras.

Non-Living Event Air-Borne Sounds

This category would include, impact events, earthquakes, volcanoes, and explosions.

An impact event is a collision between astronomical objects causing measurable effects. Most involve asteroids, comets, or meteoroids. The greatest of these in recorded history is the Tunguska Event.

Tunguska Event – Impact Event

The Tunguska event was an explosion that occurred about 3 to 6 miles above the earth’s surface due to a meteor, asteroid, or comet air burst in 1908. This was near Krasnoyarsk Krai, Russia, a sparsely populated area (Figure 1), and the sound level was said to have reached about 300 dB (based on estimates from damage to the trees, to be equivalent to a 1000-megaton bomb, but estimates vary). It destroyed about 830 square miles of forest, and is considered the largest impact event in recorded history, even though there was no firm evidence that it actually made physical contact with the earth as would be expected from a collision.

Figure 1. Location of the Tunguska Event (left image) and 830 square miles of forest aftermath, as reported from a Soviet Academy of Science 1927 expedition by Leonid Kulik.

Krakatoa – Explosion

An explosion is a rapid increase in volume and release of energy in an extreme manner, usually with the generation of high temperatures and the release of gases. A volcano eruption is a natural explosion, and so it was with Krakatoa.

“So cataclysmic was this event – which happened at 10:02 on the morning of August 27, 1883 – that the volcano’s ripping-itself-apart sounds were heard thousands of miles away1.”

Figure 2. A lithograph of the Krakatoa volcano eruption made about 1888, five years following the eruption. Image: Parker & Coward/Wikipedia.

An immense wave then leaves Krakatoa at almost exactly 10:00 A.M. – and then, two minutes later, according to all the instruments that record it, came the fourth and greatest explosion of them all, a detonation that was heard thousands of miles away and that is still said to be the most violent explosion ever recorded and experienced by modern man. The cloud of gas and white-hot pumice, fire, and smoke is believed to have risen – been hurled, more probably, blasted as though from a gigantic cannon – as many as twenty-four miles into the air2. (Figure 2).

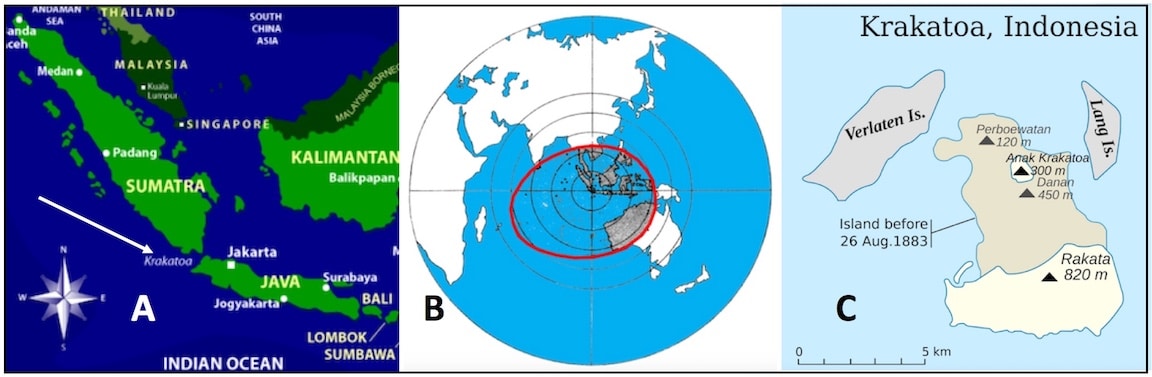

The above describes the catastrophic eruption off the coast of Java of the earth’s most dangerous volcano – Krakatoa. Krakatoa was a volcano-island (four on the island), and its eruption in 1883 dramatically changed the island (Figure 3). The immense tsunami that followed killed nearly forty thousand people3.

Figure 3. Location of Krakatoa, Indonesia in the Indian Ocean (A), area in which the eruption was heard bordered in red (B), and the change in the island following the eruption (C).

How loud was the explosion? “Consider this piece of history: On the morning of August 27, 1883, ranchers on a sheep camp outside Alice Springs, Australia, heard a sound like two shots from a rifle. At that very moment, the Indonesian volcanic island of Krakatoa was blowing itself to bits 2,233 miles away2.” Later documentation reporting on places where the eruption was heard, recorded the most distant being Rodriquez Island in the Indian Ocean, a distance of 2,968 miles3.

Scientists think this may have possibly by the loudest sound humans have ever accurately measured. In addition to the records of people hearing the sound of Krakatoa thousands of miles away, physical evidence as recorded by spikes in atmospheric pressure suggests that the sound traveled around the globe four3 to five times. It was suggested that it registered 5.0 on the Richter scale, which at its epicenter, would be about 235 dB. Based on a barometer at the Batavia gasworks (100 miles from Krakatoa), a spike in pressure of over 2.5 inches of mercury was registered, converting to over 172 dB3,5.

Nuclear bomb – Explosion

A sound level meter set 250 feet away from test sites peaked at 210 decibels. At the source, the level is reported to be from 240 to 280 dB+. It is said that the sound alone is enough to kill a human being, so if the bomb doesn’t kill you, the noise will (Figure 4).

TNT – Explosion

The detonation of one pound of TNT, measured from 15 feet away, measures at about 180 dB6.

Sustained Loud Air-Borne Sounds

Space shuttle launch

There’s a reason why everyone watches these from several miles away; the noise levels at the perimeter of the launch pad can reach 160 decibels (Figure 5). Even at the three-mile mark, the level is 120 dB. The loudest sound level recorded by NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration) was the first stage of the Saturn V rocket, that measured 204 dB.

Boeing 747 jet engine

With your head inside the engine, the level would be about 165 dB. The human eardrum ruptures when exposed to sounds greater than 160 dB or 100 kPa. At takeoff, if nearby, the level is around 140 to 1505 dB (Figure 6).

Loudest car stereo – The Ridiculous

In 2002, a group of German car engineers built a car stereo that produced 177.6 decibel sounds, breaking the previous record set by Arizona engineers. The 175-decibel speaker system was installed into a Ford Bronco, rendering the Bronco barely drivable, as the seats had to be squished so far forward to accommodate the speakers thrown in the trunk (Figure 7). This has subsequently been broken and is now at 180 dB. Now, is this just dumb or what?

Living Event Air-Borne Sounds

Animal/mammal sounds are both air-borne and water-related. And, if heard (we assume by humans), depend on frequency, duration, etc.

Water-Borne Creatures

Whales

The sperm whale’s communicative clicks have been measured at 230 dB8. The blue whale’s low-frequency calling rumbles can be heard through hundreds of miles of ocean, measuring in at about 188 dB (Figure 8).

Pistol Shrimp (snapping shrimp; alpheid shrimp)

Figure 9. Pistol shrimp showing its single large claw that is used to create a cavitation bubble to kill or stun fish. Image from Anirudh in Interesting Facts, 2/23/2013.

Also known as snapping shrimp, they produce an intense “scream.” This small crustacean (grows to only 1-2 inches) has a special pistol-like featured claw that snaps shut with such speed that it creates a cavitation bubble with extremely low pressure, creating a shock wave measured at 218 dB re 1 µPa, capable of killing smaller fish and stunning larger fish7. The duration of the click is less than 1 millisecond. It is not the two claw surfaces hitting each other than creates the sound, but the cavitation bubble that reaches speeds up to 62 m/h and collapses with a loud snap (Figure 9).

Water Boatman

Figure 10. The water boatman, a European insect, may produce the loudest sound of its size for any creature, at 99.2 dB. Wikipedia photo.

The water boatman may hold the record for a water insect, at 99.2 dB. It accomplishes this sound by rubbing its penis across its abdomen. This freshwater insect measures just 2 mm in length and is common across Europe. About 99% of the sound is lost when transferring from water to air, the sound is still loud enough to be audible to the human ear. It may produce the loudest sound of its size for any creature (Figure 10).

Land Creatures

Elephants

Figure 11. The African elephant has had its rumbling calls measured as high as 112 dB at 1 meter from the source. Photo, Wayne Staab.

The majority of the loudest animals on Earth are also the largest (Figure 11). An elephant’s rumbling calls have measured 112 dB at 1 meter from the source. While such a loud sound would be considered intolerable to humans, much of the energy falls into the infrasonic range, meaning that it falls below the frequency range of human hearing, and as a result, is not heard. For example, the typical male elephant rumble fluctuates around an average minimum of 12 Hz, more than three octaves below a man’s voice.

Winged Creatures

Bats

Figure 12. Lesser bulldog bat, capable of producing ultrasonic sounds as high as 137 dB. Photo from Stephen Dalton.

The calls of these squeaky little flighted mammals are too high in frequency for human ears to hear (ultrasonic), which is a good thing since the loudest recorded bat call clocked in at 137 decibels, about 4 inches from the bat. The high-pitched calls are used to echolocate their small, swiftly moving insect prey (Figure 12).

The sounds identified in this article are representative sounds, and the levels vary, depending on many variables. One can easily find other sounds that are shown to be just as loud as the examples shown, or maybe even be a little louder. The purpose was not to state that these were the absolute loudest sounds, but to provide some comparative data of what some of the very loud sounds are.

References

- https://www.awesomestories.com/asset/view/Krakatoa-Loudest-Sound-in-Recorded-History0

- Winchester, S. The day the world exploded. Harper Collins Publishers, New York.

- Loudest%20Sound/Krakatoa%20-%20Wikipedia.webarchive

- https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/the-loudest-sound-in-the-world-would-kill-you-on-the-spot/

- Judd, John Wesley, et al. The Eruption of Krakatoa: And Subsequent Phenomena. Trübner & Company, 1888. (a comprehensive data-filled report of the Krakatoa eruption commissioned by the Royal Society, accessible for free under public domain). https://nautil.us/blog/the-sound-so-loud-that-it-circled-the-earth-four-times

- Hamby, W. Ultimate sound pressure level decibel Table. https://www.makeitlouder.com/Decibel Level Chart.txt.

- Burton, M. and Burton, R. (1970). The International Wildlife Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, Marshall Cavendish, p. 2366.

- Davies, E. There are many ways to measure loudness, so the loudest animal on Earth may not be what you expect. Earth. https://www.bbc.com/earth/story/20160331-the-worlds-loudest-animal-might-surprise-you.

![]() Wayne Staab, PhD, is an internationally recognized authority on hearing aids. His professional career has included University teaching, hearing clinic work, hearing aid company management and sales, and extensive work with engineering in developing and bringing new technology and products to the discipline of hearing. Dr. Staab is the Founding Editor of Wayne’s World and served as the Editor-In-Chief of HHTM from 2015 to 2017.

Wayne Staab, PhD, is an internationally recognized authority on hearing aids. His professional career has included University teaching, hearing clinic work, hearing aid company management and sales, and extensive work with engineering in developing and bringing new technology and products to the discipline of hearing. Dr. Staab is the Founding Editor of Wayne’s World and served as the Editor-In-Chief of HHTM from 2015 to 2017.